A Global Conflict

Britain was at war with France for most of the period from 1793, when France declared war, until 1815. The country fought alongside a changing series of allies, including Spain, Denmark and the Netherlands. The politics of the period were complex – at times these nations were allies of France.

Britain, France and other combatant nations had overseas colonies, which were drawn into the conflict. There was fighting in the Caribbean, the Americas, South Africa and India.

Most of the prisoners held at Portchester were French, but there were also many Dutch and Spanish prisoners. Other nationalities included Americans, Danes, Germans and Italians, and Lascars from south-east Asia (Malays). This cosmopolitan mix reflected both the global nature of the war and the international make-up of some national armies. The prisoners also included soldiers’ wives and families, as well as passengers and crew from civilian ships captured by Britain.

During the 18th century warring nations tended to exchange prisoners at regular intervals. But after Napoleon seized power in France, this system broke down. The number of enemy soldiers imprisoned in Britain rocketed from 13,600 in 1795 to more than 70,000 in 1814.

A Prisoner-of-war Depot

By July 1794 the Sick and Hurt Board (which looked after sick and wounded seamen as well as prisoners of war) had commandeered Portchester Castle to hold prisoners of war. By the end of August it was ready to receive its first prisoners.

Prisoners were kept at Portchester until the Peace of Amiens was signed in March 1802. Although war broke out again in 1803, the castle was used as a barracks and ordnance store until 1810, but then became a prison again until the war ended in 1814.

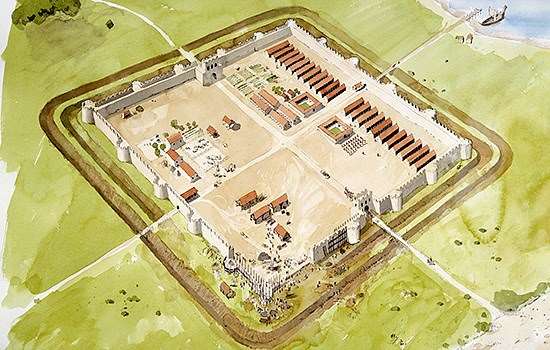

The castle could hold up to about 8,000 prisoners. They were housed both in new wooden buildings erected in the outer bailey (within the Roman fort walls) and in the castle keep and the buildings around it. Numbers varied over the years depending on the campaigns that Britain was involved in at the time – so in 1795 there were just under 5,000 prisoners at Portchester, but in 1814 there were about 7,000. At that time it was one of 12 prisoner-of-war ‘depots’ in Britain.

The Prison Layout

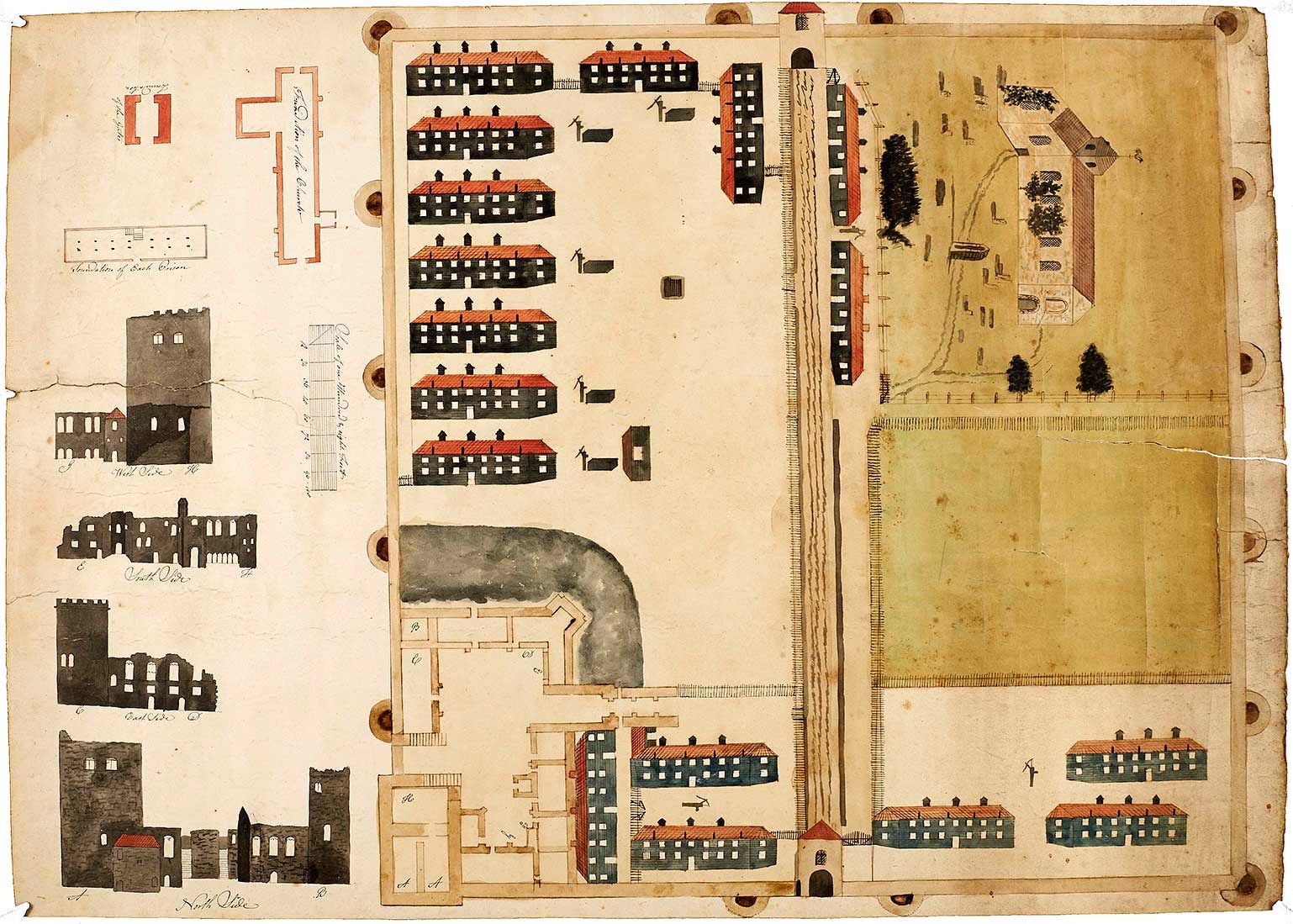

This plan, made about 1800, shows the layout of the prison, which remained little changed until the war ended. The nine main prison blocks (top), in the castle’s outer bailey, were two-storey buildings which could hold up to 500 prisoners each. The three buildings at lower right contained the prison hospital, while those at lower centre probably housed the guards.

Different nationalities tended to be kept apart within the castle to avoid conflict. During the 1790s, for example, French prisoners were held in prison blocks in the outer bailey. Spanish prisoners were housed in Assheton’s Tower (at the north-east corner of the inner bailey) and Dutch prisoners in the keep. A report by prison inspectors made in about 1796 noted that

the Dutch prisoners … have conducted themselves with the utmost propriety, remarkable for cleanliness, consequently healthy, and never been guilty of selling their clothes, or other irregularities in common amongst the French.

Prison Conditions

Conditions at Portchester could be harsh, particularly for those prisoners who gambled away their food and clothing. There were also constant complaints by the prisoners about the quality of the food. Perhaps surprisingly, many of their complaints were listened to. Both prison staff and prisoner representatives regularly inspected the food rations. Action was taken if the food was found to be substandard.

The prisoners’ daily food ration in 1801 was:

- 1½ pounds of black bread (made from rye)

- ½ pound of beef and vegetables, replaced twice a week by cod or herring and potatoes.

This was similar to the amount issued to active naval seamen, and was more than the labouring poor of Britain could often hope to get at this period. Poor people bore the brunt of the rising food prices caused by repeated bad harvests and food shortages.

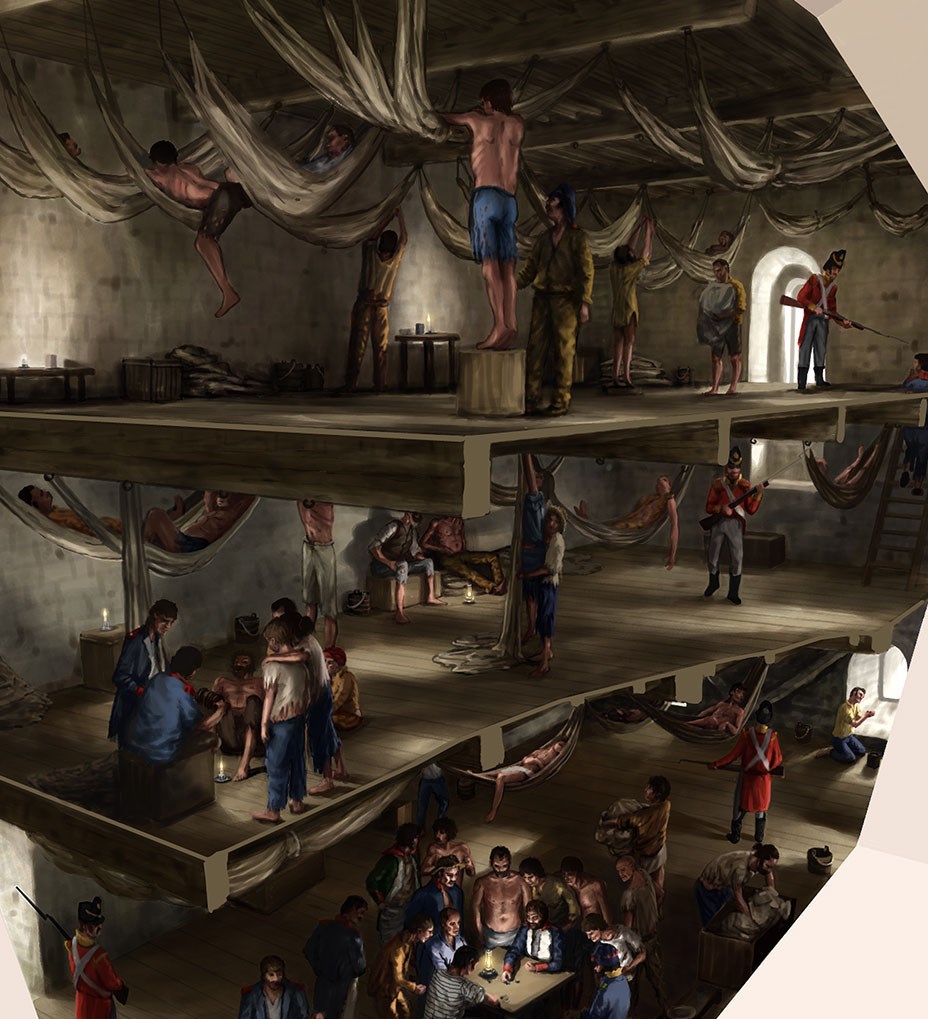

The prisoners slept in large dormitories, and each was given a hammock, mattress and blanket. There was a prison uniform of trousers, shoes or clogs, a cotton shirt, a cardigan and a jacket. The uniforms were coloured yellow to prevent them from being sold, and to identify the prisoners if they tried to escape.

Prisoners’ crafts and activities

Unlike the prisoner-of-war camps of the 20th century, the prison at Portchester was not wholly cut off from the outside world. Prison life could be monotonous, but many prisoners used their skills and expertise to pass the time productively. They could find work in the prison cookhouse and laundry, while others helped in the hospital as medical assistants and orderlies.

Portchester also had a daily market which operated in the morning until noon, except on Sundays. At the market, prisoners could sell handmade items to visitors, locals or one another. Some of the items which have survived include carved bone objects such as dominoes and playing cards, as well as more sophisticated pieces such as an intricate straw work box.

Another market, outside the castle walls, supplied produce such as food and clothing to those prisoners who could afford it.

Other activities for the prisoners at Portchester included drawing, fencing and theatrical entertainment, as well as education in subjects such as languages and maths. The wide range of activities reflected the fact that the prisoners came from all walks of life, and many were highly skilled.

For some prisoners, selling their creations could be a lucrative business. An English officer, Ambrose Serle, wrote in 1800:

The Prisoners are allowed to sell any kinds of their own manufacture … by which some have been known to earn, and to carry off upon their release, more than a hundred Guineas each. This, with an open market … operates much to their Advantage and Comfort; and they shew their satisfaction in their Habits of Cheerfulness peculiar to themselves.

Some prisoners were even skilled forgers. The Bank of England Museum has a number of forged bank notes within its collection made by prisoners of war at this time.

Prison ships

By 1796 prisoner of war numbers at the castle had increased and two prison ships – the Captivity and the Vigilant – were moored in Portchester Lake, a deep water channel near the castle. They were intended to provide extra capacity to assist Portchester and the other prisoner-of-war prison, Forton, in nearby Gosport. In 1797 five more ships were commissioned, and eventually there were about ten in Portchester Lake.

Prison ships (or hullks) were generally either decommissioned ships no longer needed by the navy or captured enemy vessels. Perhaps the most famous is the Temeraire – immortalised in JMW Turner’s famous painting The Fighting Temeraire – which was decommissioned and used to hold prisoners of war in Plymouth between 1813 and 1819.

Each hulk could hold about 850 prisoners, although not all of them did. Described as ‘floating tombs’ by Captain Charles Dupin, the hulks had a bad reputation among prisoners of war. Conditions were often worse than in the land prisons, mainly because they were so crowded. The food rations were the same as at Portchester, but epidemics such as typhus and dysentery could spread quickly through a hulk. But there were doctors on board many of the ships, and some hulks served specifically as hospitals and for convalescents.

Prisoners on parole

Not all prisoners of war were held in the prison ships or in prisons. Captured officers were treated differently from the ordinary soldier or sailor. Many officers were allowed to live relatively normal lives in towns and villages on parole – meaning that they had given their word that they wouldn’t try to escape – while they waited to be exchanged with captured British soldiers and sailors in France.

Over 60 towns and villages across the British Isles were designated as ‘parole towns’. There were two close to Portchester – Bishop’s Waltham and Hambledon – and four elsewhere in Hampshire (Alresford, Odiham, Andover and Petersfield).

To be allowed to live on parole, enemy officers had to agree to abide by certain conditions. These included keeping to a curfew, promising not to escape and restricting their movements to within a mile of the village limits. In return the officers received a payment twice a week to help pay for their accommodation and food. They could also receive money from home and some even had their families and servants living with them.

Of course some did try to escape, but others made the best of the situation and gave lessons in French, dancing, or fencing while they waited to be released.

Returning home

Prisoners of war in the 18th century did not expect their captivity to last until hostilities ended. Most would be returned to their home countries as part of regular prisoner exchanges. Prisoners of war were expensive to look after, and Britain was keen to return as many as possible.

During the early part of the war prisoners were exchanged regularly. The prison doctors decided who would be sent back. They often chose to return many of the sick and wounded, who were not only costly to look after but also unlikely to be sent back to front line duty.

After 1803, however, as mistrust grew between France and Britain over prisoner exchanges, far fewer prisoners were sent home. Most remained in captivity until hostilities ended in April 1814. Then all the prisoners at Portchester were quickly released. Large numbers of ships carried them from Portsmouth to France, and a money changer was even employed so that they could exchange their pounds for francs. By May 1814 the castle was finally clear of prisoners, and the prisoner-of-war buildings were auctioned off on 12 July 1814.

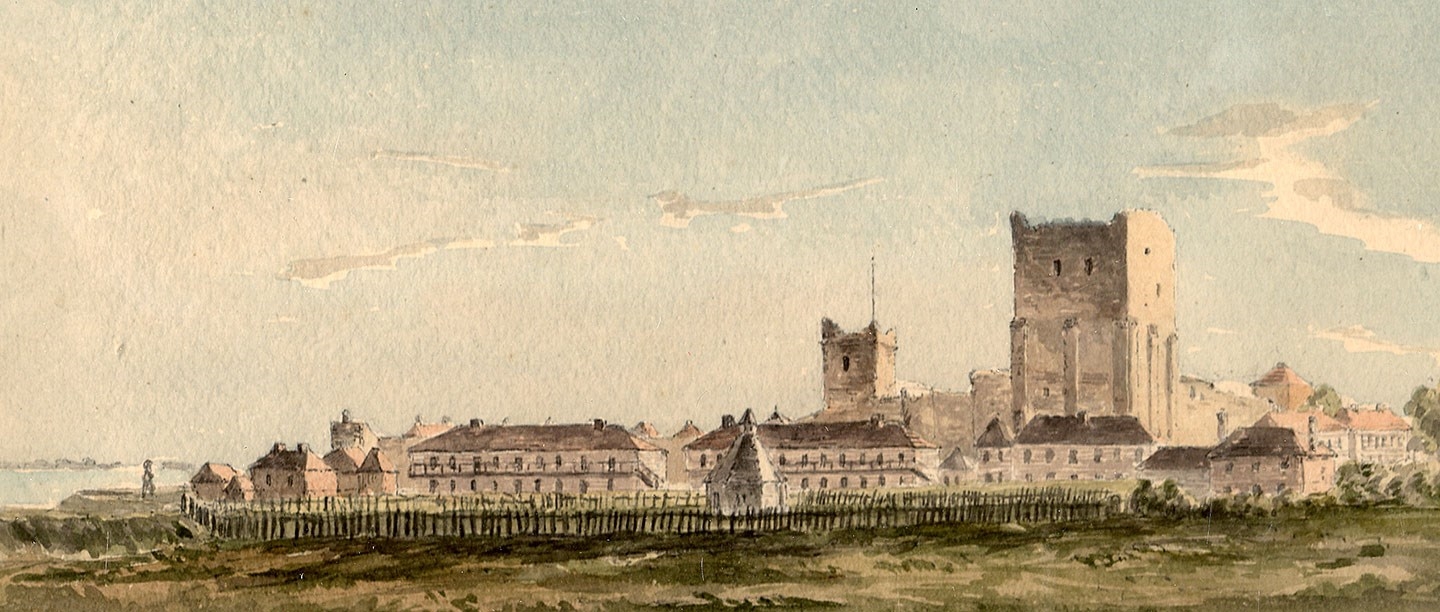

Top image: Portchester Castle in use as a prison in about 1810, by Captain Durrant (© Hampshire Cultural Trust)

Find out more

-

Black prisoners at Portchester Castle

Read the extraordinary story of a group of over 2,500 prisoners of war who were brought to Portchester Castle in 1796 from the Caribbean island of St Lucia.

-

Black people in late 18th-century Britain

How much do we know about other black people living in Britain around the time the prisoners from the Caribbean were being held at Portchester?

-

The prisoners' theatre at Portchester Castle

Find out about the theatre set up and run by French prisoners of war at Portchester Castle between 1810 and 1814.

-

History of Portchester Castle

Read a full history of the castle, from its origins as a Roman fort, through its development as a medieval castle and its role as a prison, to the present day.

-

Listen to Speaking with Shadows

In the episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast, Josie Long visits Portchester Castle to learn about the black prisoners of war who were imprisoned there in the 18th century.