D-Day’s Bodyguard

‘In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.’ (Winston Churchill)

War is not only about fighting. It is also about intelligence-gathering, much of which is clandestine work done by spies who seek to learn the enemy’s plans, and to sow lies with the enemy to deceive them.

From July 1943, a secret group of military officers, known as the London Controlling Section, began to devise a large-scale deception operation, codenamed Bodyguard. Deception methods had been practised and refined over the previous three years of the Second World War so that, by the time of Bodyguard, it was recognised that the foundation of all such operations was to support and encourage the expectations of the enemy, carefully reinforcing what you wanted them to believe, and ensuring that information reached the highest levels of command.

Bodyguard’s key objective was to mislead the Germans about the timing and location of the Allied invasion of north-western Europe. Operation Fortitude South, one of its main elements, aimed to convince them that the invasion would be via the Pas-de-Calais.

Ultra and Double Cross

The Allies were assisted in this deception by two important factors.

The first of these was Ultra – the codename for the intelligence received from Bletchley Park, where a crack team of codebreakers had successfully broken the German secret coding system Enigma. The Germans, convinced that Enigma could not be broken, remained totally unaware of this fact and their consequent vulnerability. So the Allies could check the success of any information, or misinformation, that they planted, by intercepting and reading the decoded responses.

The second factor was Allied control of several double agents by the Twenty Committee of MI5, the British intelligence agency, under the Double Cross System. Their direction of these agents was such that the Germans were completely unaware that they were being constantly manipulated.

Operation Fortitude South

The key manipulation was to make the Germans believe that the invasion would take the shortest and most obvious sea crossing, from Dover to the Pas-de-Calais. This aimed to ensure that German defences and troop concentrations in that region were the strongest in the whole ‘Atlantic Wall’, and weaker where the real invasion would fall – in Normandy.

As a part of the wider Bodyguard plan, Operation Fortitude South was designed to reinforce this belief. It also aimed to make the Germans think that the invasion of Normandy, when it happened, would be a diversionary attack, so that, for as long as possible after the real invasion, they would still believe that the main invasion would be coming from the Dover area. This would ensure that they would not divert German forces from the Pas-de-Calais to provide reinforcements in Normandy.

A fake army

The major part of Fortitude South was a sub-operation called Quicksilver I, the creation of a fictitious army – the First United States Army Group (FUSAG) – stationed in south-east England under General George Patton. Patton was chosen to reinforce the idea that his would be the major assault, as he was the senior American field commander and the one most feared by the Germans.

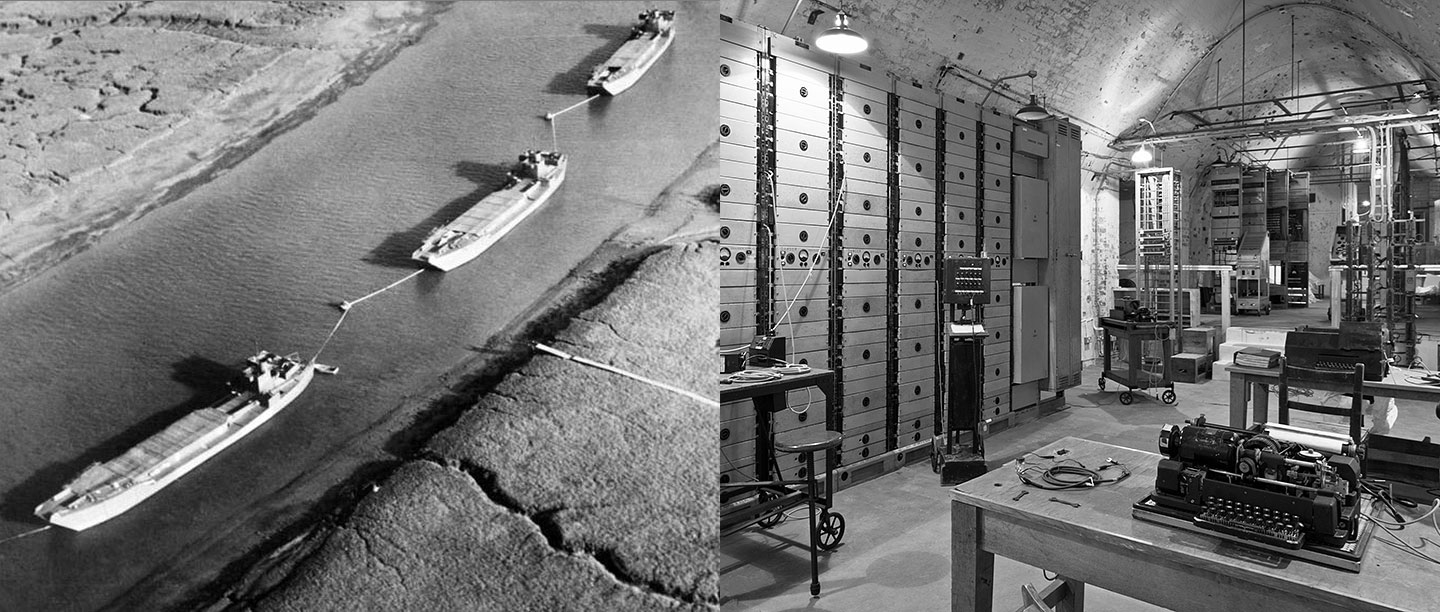

To strengthen the illusion of FUSAG preparing to embark, dummy landing craft were made from scaffolding tube, wood, canvas and empty 40-gallon barrels. Very convincing when viewed from a distance and from the air, these were assembled and deployed in harbours and estuaries around the south-east, centred on Dover. Large numbers of dummy tanks and vehicles were deployed in groups all over south-east England, to simulate an army preparing to move.

At the same time, a huge volume of fake radio traffic was transmitted and received by fixed and mobile units across south-east England. This was supported by the double agents’ frequent but careful ‘leaks’ about the make-up and position of FUSAG units.

A real army

In reality, many of the units that were supposedly part of FUSAG were never in the south-east. Most were moved from locations in north-west England to places further west along the south coast, at Weymouth and Southampton, ready to embark for Normandy as part of General Montgomery’s real invasion force.

However, early in 1944 there were some real soldiers in Kent and the south-east, comprising most of the 1st Canadian Army. The 2nd Canadian Corps was based at Temple Ewell and the 2nd Canadian Infantry at River, both near Dover. Signallers from these forces operated from several locations, to send the mass of dummy signals traffic.

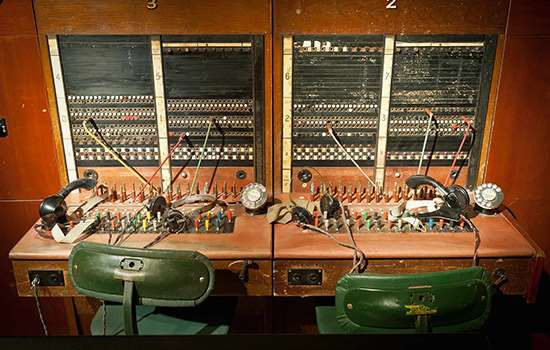

One of these sites was the underground tunnels in Dover Castle.

Dover Castle’s tunnels and Operation Fortitude

Dover Castle had played a key role earlier in the war, when its tunnels housed the command centre for the evacuation of Dunkirk (Operation Dynamo) in May–June 1940. The castle then figured prominently from 1942 in Allied planning for the invasion of Europe, as one of three potential centres for a Combined Operations HQ to direct the invasion. As a result, to handle the expected real increase in telephone and teleprinters traffic, a signals centre with a repeater station – code-named Q Dover – was established in the Dover Castle tunnels.

For weeks on end in the spring of 1944, British and Canadian units worked in the tunnels around the clock, sending a host of coded fake radio messages all over Britain to simulate the communications of FUSAG, as if preparing for an invasion. It was all encoded, so the signallers had no idea what they were sending. However, they knew it was important because of the requirement to work around the clock in relentless eight-hour shifts, seven days a week.

Success

The startling success of Bodyguard, and especially of Fortitude South, is reflected in German belief in the existence of FUSAG as late as August 1944, two months after the D-Day landings. As a result, the Germans kept vital units away from the main fighting front in Normandy, because they were still expecting a second, larger invasion in the Calais area.

Operation Fortitude South saved thousands of Allied lives and helped to ensure that a firm foothold was established at the beginning of the liberation of Europe.

By Paul Pattison

Top image, left: The repeater station at Dover Castle; right: dummy landing craft in an estuary in south-east England, 1944 (© IWM H 42527)

Related content

-

The Fall of France in 1940

On 22 June 1940 the French government surrendered to Hitler, just six weeks after the Germans’ initial advance westwards. Find out why France collapsed so quickly.

-

Operation Dynamo: Things You Need to Know

Find out the key facts about Operation Dynamo, the near-miraculous evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940, which was controlled from Dover Castle’s tunnels.

-

Episode 267 - Day of reckoning: remembering the events of D-Day

We reveal the story of the biggest landing by land, sea and air the world has ever seen, and how it helped bring about the end of the Second World War.

-

History of Dover Castle

Discover the castle’s long history, from its likely origins as an Iron Age hillfort, through its development as a great fortress, to its secret role in the Cold War.

-

Wartime Tunnels Collection Highlights

From weapons and technology to uniforms and personal possessions, these objects provide a glimpse into the lives of those who served in the castle’s tunnels.

-

Visit Dover Castle

Immerse yourself in nine centuries of history at this most iconic of English fortresses, where you can still visit the secret wartime tunnels deep within the White Cliffs.