Sunburst star turban

Astraea heliotropium

Distribution: New Zealand

Size: 75mm

Named for its shape, this shell is an exciting link back to Captain Cook (1728–79) and his voyages around the world. Brought back to Europe by the officers and crew who sailed the world, this shell is endemic to New Zealand, so can only have come from that place.

Precious wentletrap

Epitonium scalore

Distribution: Indo-Pacific

Size: 65mm

The whorls of this unique shell are not tightly joined together as usual, but are held together by a series of ridges, which leaves gaps between the whorls. The precious wentletrap was thought to be extremely rare so in the 17th and 18th centuries they were sold for hundreds of pounds. Counterfeits were made using rice flour to take advantage of the high price to be gained by selling these shells.

Noble pen shell

Pinna nobilis

Distribution: Mediterranean Sea

Size: 300mm

The creature that lived within this shell secretes long silk-like threads, known as byssus, from a gland in its foot to anchor itself into the sand. Byssus was harvested to be spun and woven into cloth. Both Pope Benedict XV and Queen Victoria had a pair of byssus stockings. It was extremely expensive as approximately 1,000 shells are needed to produce around 250g of yarn, so its use declined in the 19th century, and died out just after the First World War.

Chambered Nautilus

Nautilus pompilius

Distribution: Indo-Pacific

Size: 160mm

The nautiloid, the animal living in this shell, has around 90 tentacles. It lives in the outer chamber of the shell. As it grows, it creates a larger chamber and seals off the vacated one. These shells have been carved and engraved for centuries, and were among the most coveted natural history items for collectors.

Paper Nautilus

Argonauta argo

Distribution: Worldwide in warm waters

Size: 230mm

Not in fact a shell, but a protective egg case, it is built by the female to keep her thousands of eggs safe as she swims. After the eggs hatch, the case is discarded. It is extremely thin and delicate. Despite the name, these creatures are more closely related to the common octopus than to the chambered nautilus.

Shipworm crypt

Kuphus polythalamius

Distribution: Philippines

Not technically a shell, this tube is the casing made by the animal Kuphus, to allow it to live in its preferred habitat, the mud of mangrove swamps. Typically, they can measure up to 1 metre in length, though this exampkle is 34 centimetres long. The narrow end is the top, which is open to allow for feeding and breathing through siphons.

Queen Scallop

Aequipecten opercularis

Distribution: East Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean

Size: 55mm

One of a few bivalve molluscs that can swim and so can move quickly when threatened. It fills its mantle cavity with water, then claps the valves shut, forcing the water out in a jet. This propels it through the water in short bursts.

Atlantic Thorny Oyster

Spondylus americanus

Distribution: North Carolina to Brazil

Size: 150mm

These shells cement themselves to rocks or piers, and their shape varies according to where they are anchored. It is common for algae, sponges or coral to grow among the spines, creating a microhabitat, and excellent camouflage. In 1804, Bridget asked her son Matthew to collect her a prickly oyster from where he lived in Jamaica. If he was successful, this could be that shell!

Fluted giant clam

Tridacna squamosa

Distribution: Philippines, Indian Ocean, Red Sea

Fluted giant clams are extremely important to the coral reef ecosystems they inhabit. Whilst this specific species of clam is not currently at risk of extinction, other clams are. All species of giant clams now have protection to try to control their collection and sale under the International Union of Conservation. This is because controls are needed to prevent more species becoming at risk.

-

History of Chesters Roman Fort

One of a series of permanent forts built during the construction of Hadrian’s Wall, Chesters housed some 500 cavalrymen.

-

Bridget Atkinson

Read about the life of Bridget Atkinson (1732–1814), a Georgian collector of shells.

-

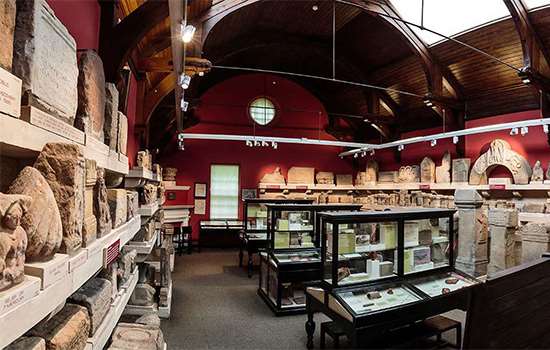

Chesters Collection Highlights

The Clayton Collection at Chesters is made up of Roman finds from multiple forts, milecastles and turrets along Hadrian’s Wall.