An unwelcome legacy

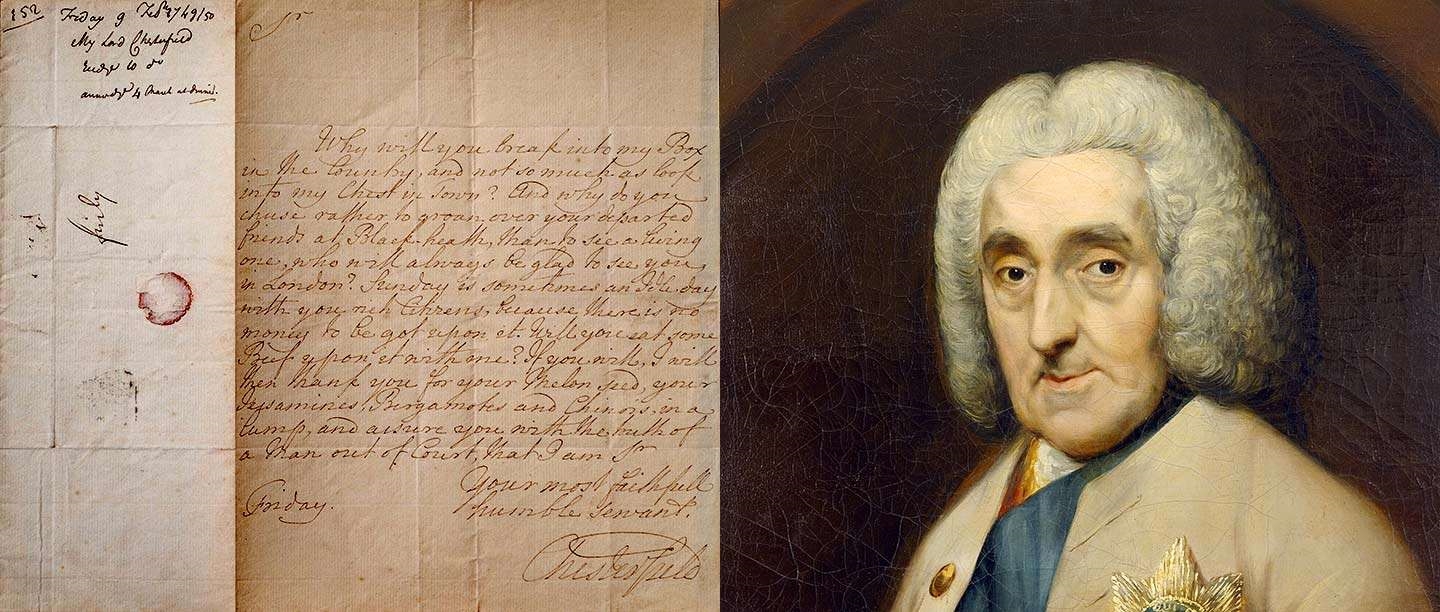

Lord Chesterfield inherited the property now known as Ranger’s House on the death of his younger brother in 1748. At first, this was something of an unwelcome legacy. He wrote:

I am obliged to keep that place for seven years, my poor brother’s lease being for that time; and I doubt I could not part with it, but to a very great loss, considering the sums of money that he had laid out upon it.

Chesterfield continued, ‘I own that I like the country up, much better than down, the river’. It seems he would have preferred a suburban retreat further west along the river Thames in Twickenham or Richmond, and near his friend Henrietta Howard, who lived there at Marble Hill.

None the less, he soon came to embrace life at Ranger’s House, then known as Chesterfield House. It no doubt helped that his inheritance at the age of 54 coincided with his gradual withdrawal from political life.

Read more about Henrietta HowardFrom politics to ‘philosophical quiet’

Lord Chesterfield was an accomplished politician and diplomat, known for his skilled oratory in the House of Lords. He served from 1728 until 1732 as ambassador to The Hague, and later as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland (1745–6) and as Secretary of State for the Northern Department (1746–8).

In 1748, the same year Chesterfield inherited his brother’s house, he resigned from government in protest at foreign policy. He was also tired of the stresses and strains of a public career. Although he still attended the House of Lords – his last speech was in 1755 and, as he described it, ‘near annihilated’ him – this marked the start of his gradual withdrawal from politics.

In 1748 Chesterfield wrote to his godson and friend Solomon Dayrolles:

I shall now, for the first time in my life, enjoy that philosophical quiet, which, upon my word, I have long wished for.

Altering Chesterfield House

In spite of his initial reservations about his new home, Chesterfield quickly set about transforming it. Perhaps the most dramatic alteration was the addition of a large gallery to the south, the shell of which was built by June 1750. This addition nearly doubled the size of what was a relatively modest gentleman’s residence, and even encroached illegally into Greenwich Park.

The designer was most likely the architect Isaac Ware, who was also building Lord Chesterfield’s Mayfair home, Chesterfield House (now demolished). Of his architectural endeavours Chesterfield wrote:

I have not yet been able to get the workmen out of my house in town … One would think that I liked them, for I am now full of them at Blackheath.

Once the gallery was built, Lord Chesterfield boasted that it gave him ‘three different, and the finest, prospects in the world’. Views to the north took in Greenwich Park, the village of Blackheath was to the south, and from the north-west were views over Hyde Vale towards London.

Chesterfield was a keen collector of paintings, and the new gallery was no doubt built to accommodate some of his extensive collection of Old Masters. A sales catalogue of the house’s contents in 1782 (after the death of Chesterfield’s heir) almost certainly describes how the rest of the house looked in Chesterfield's day. Rooms were variously decorated with damask, elegant japan, gilt and mahogany furniture, and plaster busts were displayed in the Hall and elsewhere. The catalogue also notes a number of ‘curious astronomical and musical clocks’ and a ‘well-chosen library of books’. This was the home of a man of taste.

To run his new household Chesterfield employed as many as 18 servants, accommodated in the basement and most likely in a new block of offices built in the Stable Yard. The upper servants, including the steward, butler and cook, had their own bedchambers. Some of these were hung with prints and had mahogany furniture.

A life of retirement

Lord Chesterfield spent his summers at Ranger’s House. He dedicated his time there to reading, writing and gardening – occupations, he wrote, which ‘my former youth and spirits would have despised, but which now stand in the stead of pleasures with me’. Seized by furor hortensis (garden madness), he found great enjoyment in his ‘acre of ground’ at Blackheath which, he wrote, afforded him ‘more pleasure than kingdoms do to Kings’. In his letters he mentions the cultivation of pineapples and melons and ‘conversing’ with his vegetables.

By 1752 Chesterfield was increasingly in poor health and was losing his hearing. With this, perhaps, he came to value the seclusion of his Blackheath house even more – he describes it as ‘my hermitage’ or ‘Petite Chartreuse’, after the remote monastery in the French Alps. As he wrote in 1753:

Retirement was my choice seven years ago; it is now become my necessary refuge … My little garden, the park, reading and writing, kill time there tolerably; and time is now my enemy.

Chesterfield did not become entirely isolated, however – he still entertained visitors and hosted or attended card parties. He also wrote hundreds of letters from Blackheath.

Lord Chesterfield’s family

In 1733 Chesterfield had married Petronilla Melusina von der Schulenburg, daughter of George I by his mistress, Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal. With their marriage came a considerable marriage portion and pension and later, on the duchess’s death in 1743, a substantial inheritance. Both his marriage to the king’s daughter, and later Chesterfield’s threat of a lawsuit when George II was unwilling to pay Lady Chesterfield’s inheritance, resulted in a tense relationship between Chesterfield and the Crown.

Chesterfield and his wife spent little time together. Their marriage appears to have been one of convenience and it is likely that Lady Chesterfield rarely visited Ranger’s House. There are, however, hints of her presence. The 1782 sales catalogue describes Lady Chesterfield’s Dressing Room furnished with japanned and bamboo furniture.

Chesterfield had no children by his wife. However, in 1732, the year before his marriage, he had an illegitimate son, Philip, by a young French governess, Madame du Bouchet, whom he had met when ambassador at The Hague.

THE LETTERS

Between the age of five and his death at 36, Philip Stanhope received 448 letters of advice from his father. These were at their peak in the years after Chesterfield inherited his Blackheath home – he wrote around 200 there. This extensive correspondence was intended to guide and shape Philip for a career in politics or diplomacy. Chesterfield wrote to a friend of his son in 1751: ‘His success in the world is now the only object I have in it.’

Chesterfield’s wry and witty letters of worldly advice addressed a range of subjects, from bad habits, clothing, manners and deportment to history, politics and art. From 1761 he also wrote to his godson, also called Philip Stanhope (known as Sturdy), his eventual heir.

Chesterfield’s Letters were published after his death by his son’s widow. They became a manual for gentlemen of the day, which was both extensively published and the subject of criticism. It is for his letters that Chesterfield is perhaps most celebrated today.

Image: A portrait of Philip Stanhope, Lord Chesterfield’s godson and heir, by John Russell, made about 1775. Philip was one of the main recipients of the 4th Earl’s famous letters

Lord Chesterfield’s advice

‘Tell stories very seldom, and absolutely never but where they are very apt, and very short … beware of digressions’

‘Use and assert your own reason; reflect, examine, and analyse everything, in order to form a sound and mature judgement’

‘Wear your learning, like your watch, in a private pocket’

‘Great learning, if not accompanied with sound judgement, frequently carries us into error, pride and pedantry’

‘Advice is seldom welcome; and those who want it the most always like it the least’

Further reading

Julius Bryant, Finest Prospects: Three Historic Houses – A Study in London Topography (London, 1986)

Julius Bryant, The Wernher Collection at Ranger’s House (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2002) [buy the guidebook]

John Cannon, ‘Stanhope, Philip Dormer, fourth earl of Chesterfield (1694–1773)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn 2012) (subscription required; accessed 16 July 2018)

Anne French, Ranger’s House (English Heritage guidebook, London, 1992)

Lord Mahon (ed), The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, vol 3 (London, 1845) (accessed 20 July 2018)

Lord Mahon (ed), The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, vol 4 (London, 1845) (accessed 20 July 2018)

FIND OUT MORE

-

History of Ranger’s House

Built in the 1720s for a naval captain, Ranger’s House was later home to politicians, military officers and royals, including the Rangers of Greenwich Park, for 180 years. Discover its 300-year history.

-

Ranger’s House and Admiral Hosier’s Ghost

Find out why the death of Admiral Francis Hosier, the first resident of Ranger’s House, and the devastation of his fleet, became the subject of a scathing musical attack on the government of the day.

-

The Real Bridgerton: A Royal Duchess at Ranger’s House

Ranger’s House plays a starring role in Netflix’s Bridgerton series. But the house has its own dramatic story to tell of royals, scandal and entertainments during the era in which Bridgerton is set.

-

Highlights of the Wernher Collection

Ranger’s House is now home to over 700 works from the Wernher Collection, a world-class collection of fine and decorative art. Explore a selection of highlights.