Life at sea

After he entered the Navy at the age of about 12, Hosier’s progression was steady. In 1692 he had been made a lieutenant, and by 1696 he was a commander. He was suspended after the accession of George I in 1714, being ‘spoken of as one not well affected to the protestant succession’. But in 1716–17 he was reinstated, and in 1722–3 he was made vice-admiral of the blue.

He probably made his fortune by investing in ships’ cargoes, or from booty gained from capturing other ships.

Life at home

Hosier’s domestic arrangements reflected this advance and the fortune he had made. In 1700 he was living in part of a house at Blackheath on the site of Ranger’s House. By 1717 he occupied the whole house, and was married with a daughter. By 1723 he had built the house anew, and it is his red brick villa that now forms the core of the present Ranger’s House. Its designer, John James, included the sea god Neptune as a keystone above the front door.

Hosier’s villa was fashionable, with views into the royal park at Greenwich and across the heath towards London. Although much of his life was spent at sea, this was to be his home for another five years. Unfortunately for his wife, it seems he didn’t plan for his death: he died without a will, leaving her to spend several years in a debtors’ prison contesting the estate with his nephew.

But his death was soon to acquire a significance that went well beyond a family quarrel.

Death at sea

In March 1726, Hosier was sent with 20 ships to blockade Porto Bello, a port on the coast of modern-day Panama, to prevent Spain from shipping gold home to fund its wars. Britain was not then officially at war with Spain in the Caribbean, however, so Hosier was under strict government orders not to capture the port itself.

Bound to loiter at sea for months on end without fresh supplies, his men succumbed to tropical fever. The loss was catastrophic. Four thousand men died, and Hosier himself fell victim on 25 August 1727.

The disaster had not been forgotten 12 years later, by which time the rules of engagement had changed. In 1739 Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon took the poorly defended Porto Bello easily with only six ships, at the start of the War of Jenkins’ Ear between Britain and Spain.

Murder ballad

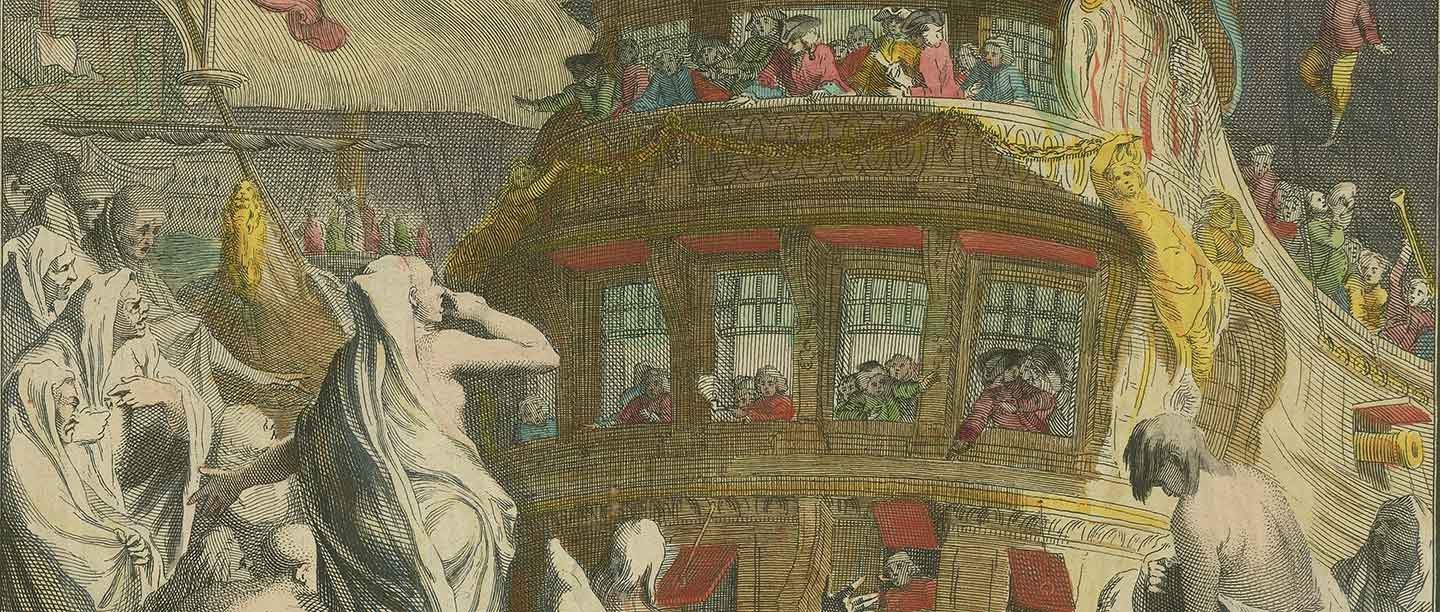

A ballad published the following year ensured that Hosier’s sorry fate would be assured for posterity. Admiral Hosier’s Ghost, by Richard Glover, imagines a spectral crew of dead sailors, led by Hosier himself, appearing to Vernon and his celebrating men:

Heed, oh heed! my fatal story,

I am Hosier’s injur’d ghost;

You who now have purchas’d glory

At this place where I was lost;

Tho’ in Porto Bello’s ruin

You now triumph, free from fears,

Yet to hear of my undoing,

You will mix your joys with tears.

The ballad was, in reality, a stinging broadside directed at the then prime minister, Robert Walpole, and his government, in its representation of Hosier’s death as the direct result of a policy of appeasement and inaction. As the ghost of Hosier laments:

I, by twenty sail attended,

Did this Spanish town affright,

Nothing then its wealth defended

But my orders not to fight;

Oh that, with my wrath complying,

I had cast them in the main,

Then, no more unactive lying,

I had low’red the pride of Spain.

Hosier’s ghost concludes by exhorting Admiral Vernon to remind those at home of his sailors’ sorry fate:

But remember our sad story,

When to Britain back you sail!

All your country’s foes subduing,

When your patriot friends you see,

Think on vengeance for my ruin,

And for England shamed in me.

By Richard Lea

Find out more

-

History of Ranger’s House

Built in the 1720s for Hosier, Ranger’s House was later home to politicians, military officers and royals, including the Rangers of Greenwich Park. Discover its 300-year history.

-

Lord Chesterfield at Ranger’s House

Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, politician and famed letter-writer, was the most celebrated owner of Ranger’s House. Find out more about him and his life there.

-

Highlights of the Wernher Collection

Ranger’s House is now home to over 700 works from the Wernher Collection, a world-class collection of fine and decorative art. Explore a selection of highlights.

-

About the Wernher Collection

Find out more about the Wernher Collection, the 19th-century businessman behind it, and how this unique collection came to be displayed at Ranger’s House.