Dido’s Mother: Maria Bell

Dido Elizabeth Belle was the illegitimate daughter of Sir John Lindsay (1737–88), an officer in the Royal Navy, and an African woman named Maria Bell(e). We do not know where or how Maria and Lindsay first met, but during 1760 his ship, the HMS Trent, was sailing around the coasts of Senegal and the Caribbean.

The first record of Maria is on Dido’s baptism entry of November 1766, at St George’s Church, Bloomsbury, in which Maria Bell is noted as the mother, and Dido Elizabeth is five years old. Lindsay is not recorded as the father, but he probably supported Maria over the next ten years, or at least stayed in contact, as in 1774, Maria travelled from England to Pensacola, America, to take possession of a plot of land gifted to her by Lindsay, where she was to build a home.

In the Pensacola property record, Maria is referred to as previously being enslaved: ‘a Negroe Woman of Pensacola in America but now of London afore and made free’. The price to confirm her freedom is dated 22 August 1774, the manumission transaction for ‘the sum of two hundred Spanish milled dollars … paid by Maria Belle a Negro Woman Slave about twenty eight years of age’. As Dido had been born in 1761, this would place Maria as a young mother of around 15 years of age at the time of Dido’s birth. The spelling of Bell had now become Belle, which is consistent with all later written records that we have for Dido.

Sir John Lindsay

From 1757 to 1767, Lindsay was sailing around Jamaica and West Africa, Haiti, Cuba and America, in a period when Britain was engaged in the Seven Years War – a war with France and her allies over the ownership of the colonies in America and the Caribbean. The Royal Navy’s ships were used to protect British trade routes, and up until 1807 and the abolition of the British slave trade this included protection of the British slavers as well as capture of enemy ships and their cargo as prizes.

Lindsay is referred to as Dido’s father in several sources, but the most puzzling one relating to Maria, is by a guest at Kenwood in 1779. William Hutchinson, an American visitor remarked on Dido’s presence, and recalls being told that her mother had been a slave on a Spanish ship captured by Lindsay, and brought to England.

Lindsay had certainly been involved in the capture of several foreign ships, including French, Dutch and Spanish – not all of which were slave trade ships – and in 1762 he had fought in the battle for Havana, where Spanish ships were taken. However, as Dido was born in 1761, Hutchinson’s remark does not help solve the mystery of how or when she came to England.

During this time Lindsay fathered more illegitimate children, with Dido being the eldest of five children by five different mothers, of whom four were certainly of African heritage. The mothers and infants, all except for Maria and Dido, are recorded in the baptism records at Port Royal, near Kingston, Jamaica, where the Royal Navy had a base for repairing their ships.

Of Lindsay’s surviving children, Dido was entrusted to the care of her father’s uncle William Murray, Lord Chief Justice and later 1st Earl of Mansfield, owner of Kenwood in north London.

Life at Kenwood

It was not unheard of for a powerful aristocrat to be the legal guardian to an illegitimate relation. But it was extremely unusual at this time for a mixed-heritage child – who had been born to a formerly enslaved mother – to be raised not as a servant, but as part of an aristocratic British family.

Dido’s exact position within Lord Mansfield’s household is unclear, but the evidence suggests that she was brought up as a lady alongside her cousin Elizabeth Murray. We know that she was taught to read, write, play music and was graceful and at ease in the presence of invited guests. She also received an annual allowance. In John Lindsay’s obituary, which confirmed him as Dido’s father, the London Chronicle noted that ‘[her] amiable disposition and accomplishments have gained her the highest respect from all his Lordship’s relations and visitants’.

Dido also supervised Kenwood’s dairy and poultry yard, a common hobby for genteel women at the time. Her daily activities however would have changed on the death of Lady Mansfield in 1784, and on the marriage in 1785 of her cousin Elizabeth. Dido remained at Kenwood without the close companion with whom she had grown up. Now a young woman in her twenties, Dido would have become increasingly involved in the care of Lord Mansfield in his old age, and in turn, he treated with her with affection. Dido’s health and comfort were also cared for, her birthday remembered in June each year with a gift of 5 guineas.

An unusual portrait

The only known portrait of Dido Belle shows her standing beside her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray on the terrace at Kenwood. Elizabeth was also brought up in the care of Lord Mansfield at Kenwood after her mother’s death in 1766. Elizabeth was just a year older than Dido and they would have been close companions. While recalling Dido’s story, Hutchinson describes Dido in 1779:

A Black came in after dinner and sat with the ladies and after coffee, walked with the company in the gardens, one of the young ladies having her arm within the other.

The portrait of the two women is highly unusual in 18th-century British art for showing a mixed-race woman as the equal of her white companion, rather than as a servant or slave. The artist, David Martin, seems to portray a moment caught. As Dido passes by her seated cousin, Elizabeth reaches out a hand to catch her – ‘stay a moment’, she seems to be saying.

Dido’s aristocratic upbringing is apparent in her expensive silk gown and pearl necklace. However, art historians have noted that it is not just the colour of her skin that marks Dido as different. The basket of tropical fruit she carries and the turban with expensive feather that she wears suggest an exotic difference from her more conventionally styled white cousin, who is sitting reading a book.

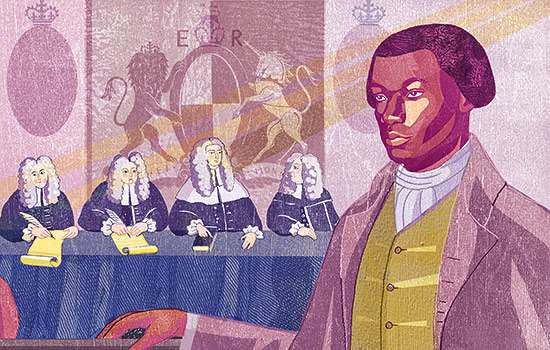

Lord Mansfield and Slavery

Dido lived at a time when the transatlantic slave trade was at its height, and Britain’s economic prosperity relied on slave labour in the Caribbean and Britain’s American colonies. However, public opinion about the practice was changing.

From 1756 to 1788 Dido’s great-uncle Lord Mansfield was Lord Chief Justice, the most powerful judge in England. He presided over a number of court cases that examined the legality of the slave trade. In the most significant of these, the case of James Somerset (1772), Lord Mansfield ruled that slavers could not forcibly send any slaves in England out of the country.

We don’t know whether his affection for Dido influenced Lord Mansfield’s opinions on the slave trade. In his summing up at the trial in 1772 he is recorded as describing slavery as ‘odious’, but as Lord Chief Justice he had to adhere to a strict reading of the law. While the Somerset case was a significant point along the road to abolition, it didn’t end the slave trade. Mansfield was clearly aware of this and in his will of 1782 he made sure to protect his niece’s rights, stating that Dido was a free woman.

It would be another 35 years after the Somerset case before the transatlantic slave trade was abolished, and a further 26 years after that before the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 finally put an end to the practice across the British Empire.

Dido’s Later Life

In contrast to her early life in the grand environment of Kenwood, Dido’s later life was of a comfortable but middling status. When he died in 1793, Lord Mansfield left her an annuity of £100 and a lump sum of £500 (approximately £40,000 in today’s money). This was a much smaller sum than that given to her cousin Elizabeth, but it is unclear if this was because of Dido’s race or her illegitimate status. Within the complicated class and status hierarchy it was not unusual for an illegitimate child to receive less financial acknowledgement, but still be regarded as a family member.

Later that year Dido married a steward (a senior servant) named John Davinier, originally from France, and the couple went on to have three sons – twin boys, Charles and John, baptised in 1795, and then another son, William Thomas, baptised in 1800. They lived in Pimlico, London, where the boys went to school, until Dido’s death in 1804 at the age of 43.

Dido was buried at St George’s Church burial ground in Tyburn (near the modern Bayswater Road). Her grave was moved during redevelopment of the site in the 1960s. There are no known surviving direct descendants; her children’s line seems to have ended with Dido’s great-great grandson, Harold Charles, who died in Johannesburg in 1975. In 2013 the film Belle, starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw, brought a fictionalised version of Dido’s story to an international audience.

The English Heritage Podcast

In this episode of the English Heritage Podcast we were joined by Cathy Power and Sarah Murden to discuss the story of Dido Belle and her life at Kenwood in north London.

Subscribe to the English Heritage Podcast to hear English Heritage experts and special guests bring the history of our sites to life.

Listen hereFurther Reading

Paula Byrne, Belle: The True Story of Dido Belle (London, 2014)

John Clune Jr and Margo S Stringfield, Historic Pensacola (2009)

Reyahn King, ‘Belle, Dido Elizabeth’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) (public library subscription required; accessed 23 Sept 2020)

Joanne Major, All Things Georgian: Dido Elizabeth Belle – New information about her siblings (2018) (accessed 23 Sept 2020)

Related content

-

VISIT KENWOOD

Kenwood’s breathtaking interiors, world-class art collection and glorious parkland are free for everyone to enjoy.

-

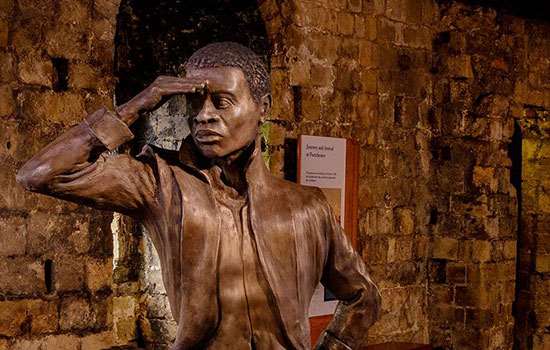

The Somerset case

The Somerset v Stewart ruling in 1772, made by Lord Mansfield of Kenwood, was a landmark in the progress towards the abolition of slavery in England.

-

History of Kenwood

Find out more about Kenwood, the mansion on the edge of London’s Hampstead Heath which was transformed by Robert Adam for Lord Mansfield.

-

Black History

Black histories are a vital part of England’s story, reaching back many centuries. There is evidence of African people in Roman Britain and black communities have been present since at least 1500.

-

Women in history

Read about the remarkable lives of some of the women who have left their mark on society and shaped our way of life – from Anglo-Saxon times to the 20th century.

-

Pioneering women in London

Discover some of London’s famous residents who took the historic first steps to open up new opportunities for women, and are now commemorated by blue plaques.