GLADSTONE, William Ewart (1809–1898)

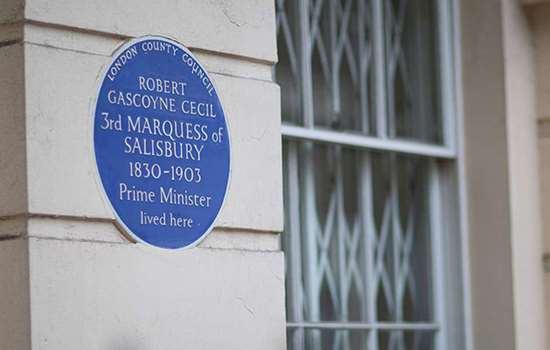

Plaque erected in 1925 by London County Council at 11 Carlton House Terrace, St James’s, London, SW1Y 5AJ, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Politician

Category

Politics and Administration

Inscription

WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE (1809-1898) Statesman Lived here

Material

Porcelain

William Ewart Gladstone was Prime Minister for four separate spells between 1868 and 1894. A major figure in 19th-century politics, he gave his name to ‘Gladstonian liberalism’, which was characterised by support for free trade and the promotion of political reforms.

Family, Slavery Links and Changing Views

Gladstone’s father, John Gladstone (1764–1851), was a Scottish-born Liverpool merchant and the owner of sugar plantations in the West Indies that ran on enslaved workers. A leading advocate for slave owners, Gladstone senior sought to obstruct or delay the emancipation of the enslaved. After emancipation passed into law he adopted the ‘coolie’ system of bringing in indentured labourers from the Indian sub-continent, before eventually selling his West Indian property.

William Gladstone himself – born in Liverpool, and educated at Eton and Christ Church Oxford – used his first speech in Parliament to defend his father against charges of cruelty to enslaved workers, while admitting that cases of this did exist. ‘He deprecated cruelty – he deprecated slavery; it was abhorrent to the nature of Englishmen; but … were not Englishmen to retain a right to their own honestly and legally acquired property?’, he asked.

On this basis, Gladstone argued for financial compensation for slave owners, and he himself benefited from his father’s tainted fortune. Later, he spoke in favour of the breakaway Confederate States in America. But he came to regret this, and in his later career was associated with internationalism and upholding the rights of non-Europeans. He told an audience in 1879 that the life of an Afghan hill villager was ‘as inviolable in the eye of Almighty God as … your own’.

Career

Gladstone began his political career as a Conservative. He served under the premiership of Sir Robert Peel as President of the Board of Trade (1843–5) and Colonial Secretary (1845–56). He supported Peel over the repeal of the Corn Laws and gravitated towards the Liberal Party, of which he became leader in 1867.

Gladstone had two stints as Chancellor of the Exchequer (1852–5 and 1859–66) in governments led by Lord Aberdeen and Lord Palmerston. His emphasis was on low government spending and free trade: he planned a notable trade deal with France, executed by Richard Cobden.

Gladstone was Prime Minister for a record four spells (1868–74, 1880–85, 1886 and 1892–94), and twice he combined this office with that of Chancellor (1873–74 and 1880–82). He was 82 when his final term at the top began – another record that still stands.

Irish ‘Home Rule’ and Other Reforms

‘My mission is to pacify Ireland’ was Gladstone’s comment on forming his first government in 1868. He disestablished the Anglican Church there in 1869 – the vast majority of Ireland’s population was Roman Catholic – and his Land Acts of 1870 and 1881 addressed economic grievances by giving greater rights to tenants. There were harsher measures too, such as the imprisonment of the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell.

However, Gladstone’s attempts to grant Ireland a measure of independence with ‘home rule’ in 1886 and 1893 both failed to get through Parliament and split the Liberal Party in the process.

Gladstone had more success with other reforms. His government brought in the first national system of elementary education in England, Wales and Scotland (1870–72), introduced the secret ballot for elections (1872) – before that voting was public, which made intimidation easy – and passed the 1884 Reform Act, which extended the vote to almost all adult males. His Railway Act of 1844 allowed for some regulation of fares and even made provision for the state acquisition of railways.

Foreign Policy and Private Life

Gladstone has been characterised as a reluctant imperialist. He was firm in his opposition to the Opium Wars but supported ‘the empire of settlement’ in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. He opposed further imperial expansion, but even while Prime Minister, his own views did not always prevail: the bombardment of Alexandria and invasion of Egypt took place under his premiership (1882) as did the first Boer War in South Africa (1880–81).

In 1879, during his Midlothian campaign for election for that Scottish constituency, Gladstone set out six principles for British foreign policy. They included ‘the love of freedom’ and ‘the equal rights of all nations’ and were an influence upon the founders of the League of Nations, among them US President Woodrow Wilson and Lord Robert Cecil.

Gladstone was a great political orator. Queen Victoria (who disliked him) complained that he spoke to her as if she were a public meeting. He was also a formidable classical scholar – among his works was Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (1858). He kept a daily diary which recorded – among much else – his self-administered beatings for the lustful thoughts he had while attempting to ‘rescue’ women who earned their living by prostitution. He carried on this missionary work even while he was Prime Minster.

Carlton House Terrace

From 1840, Gladstone and his family lived in three different houses in Carlton House Terrace – all built in a monumental Graeco-Roman style by John Nash in 1827–33 – and at another nearby in Carlton Gardens. 11 Carlton House Terrace was their London home from April 1856 until April 1875, and bears Gladstone’s highly glazed plaque with its attractive laurel-leaf border, made by Doulton.

Gladstone lived here with his wife, Catherine, and their family – they had eight children. At home, the couple read the Bible together daily and there were regular household prayers: Gladstone belonged to the evangelical wing of the Church of England.

Gladstone’s period at the house coincided with a second stint as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and with the first of his four premierships, which saw him take office in 1868. On leaving he wrote that he ‘had grown to the house, having lived more time in it than in any other since I was born, and mainly by reason of all that was done in it’.

His government lost a general election in 1874, and he resigned as Liberal Party leader the following year. There was a mortgage debt of £4,500 on number 11. So with economy in mind, Gladstone sold the house and some of his art collection, and in 1876 moved his family to 73 Harley Street for what was intended to be retirement. This house is also marked by a plaque, as is Gladstone’s later home in St James’s Square.