It’s 100 years since Cecil and Mary Chubb gave Stonehenge to the nation, and we’re marking the anniversary with a series of blog posts tracing the care and conservation of Stonehenge since 1918.

Here we look at the years between 1965 and 1977. They were marked by exciting new approaches to using and appreciating the site, bizarre theories about the monument’s origins, and some intriguing discoveries about the surrounding landscape.

Improving the experience

In 1964 a long-running excavation programme was concluded, ending a period of intensive investigation. Conservation and management works followed, including a new hard-wearing surface of clinker and gravel within the central stone setting. This levelled up the ground and created a monument that would be familiar to visitors for the next 20 years, when people could wander freely among the stones.

Visitor footfall rose steeply, from 337,000 in 1961 to more than half a million just 10 years later. The summer solstice was always popular and increasingly boisterous. From 1962 onwards, it was memorable for the barbed wire fences used to keep the crowds under control at dawn on the longest day.

More visitors meant more cars, and in 1966 the car park north of the A344 was extended. A brutalist concrete-walled underpass was built to provide easy access to the stones.

Experienced archaeologists Faith and Lance Vatcher monitored these works, and recognised three large postholes towards the western end of the new car park. When pine charcoal from these postholes was dated, it unexpectedly showed that the holes were dug in the eight and seventh millennia BC, in the Mesolithic period. This suggests a monumental presence in the landscape long before Stonehenge was conceived.

The tall, stout pine posts held in these holes have often been likened to the totem poles of indigenous peoples in north-east America.

Discoveries in the landscape

No excavations took place within Stonehenge during this period, although there were some small-scale investigations. By contrast, many important excavations took place in the surrounding landscape, especially in response to road improvement programmes.

Construction of the Amesbury bypass and the widening of the A303 east of King Barrow Ridge in 1967–8 provided an opportunity to examine the line of the Avenue – the twin parallel banks and ditches that link Stonehenge to the River Avon. These works also revealed a scatter of pits, including one that contained an unusual pair of decorated chalk plaques.

To the north, realignment of the A345 through the great henge enclosure at Durrington Walls prompted large-scale excavations led by Geoff Wainwright in 1966–8. These were the most extensive undertaken anywhere in Britain until that time.

To the west, construction of a new roundabout on the A303 at Long Barrow Crossroads in 1967 revealed a late Bronze Age settlement with at least three roundhouses. Further excavations on the Avenue revealed its line near the River Avon at West Amesbury in 1973.

A summary of work from this period was published in 1979 as Stonehenge and its Environs; it remains a useful source today.

Dating Stonehenge

New dating models emerged during the 1960s. The first radiocarbon date on material from a site in Britain, published in 1952, was based on oak charcoal from Aubrey Hole 32 (one of the ring of 56 pits just inside the bank and ditch at Stonehenge). This was processed by Willard Libby, inventor of the technique, at his University of Chicago laboratory. Three further dates on samples from Stonehenge were published in 1967. Together these placed the construction of the ditch at around 2000 BC and Y-Hole 30 (part of the ring of pits around the monument) about 1200 BC. This handful of dates aligned with prevailing models of social and cultural diffusion that set Stonehenge at the northern end of a series of connections leading back to the central Mediterranean.

However, subsequent calibration of radiocarbon dates in the early 1970s broke these supposed links and synchronisms. The revised dating pushed the origins of Stonehenge back by a thousand years. The story is well told by Colin Renfrew in his 1973 book Before Civilization. He went on to examine the implications of an essentially indigenous British monument-building tradition, linking the regularly spaced ceremonial centres across Wessex with the emergence of chiefdom societies during the third millennium BC.

Astro-archaeology

Astro-archaeology applied to Stonehenge attracted controversy during the 1960s. Much of it was triggered by Gerald Hawkins’s book Stonehenge Decoded, published in 1965. Expanding earlier papers in Nature, he suggested that Stonehenge was a Neolithic computer for predicting eclipses. Richard Atkinson’s scathing review entitled ‘Moonshine on Stonehenge’ did nothing to limit the idea’s popular appeal.

Sir Fred Hoyle, TV celebrity and Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy in the University of Cambridge, endorsed Stonehenge as an astronomical observatory in 1966. In 1975 archaeo-astronomer Alexander Thom argued that it was a lunar observatory.

Ironically, in 1984, when proposals for improving the A303 south of Stonehenge were explored by the Stonehenge Study Group, it was astronomer Richard Wort who first suggested putting the road in a tunnel, so that Stonehenge could continue to be used for its intended purpose!

Summing up the early arguments, Jacquetta Hawkes memorably noted in 1967 that ‘Every age has the Stonehenge it deserves — or desires’.

Alternative ideas

Many theories about Stonehenge and its origins appeared during the heady 1960s and early 1970s. Some, such as Erich von Daniken’s proposal in his 1968 book Chariots of the Gods that Stonehenge was connected with extra-terrestrial visitors, were plain bonkers. Others, such as Geoffrey Kellaway’s 1971 revitalisation of earlier suggestions that glaciers had moved the bluestones from the Preseli Hills in Wales to the Wessex Downs, lacked supporting evidence and were simply wrong.

In a period memorable for 1967’s ‘summer of love’, Stonehenge lived up to its reputation as an inspirational place. British sculptor Henry Moore created a suite of lithographs in 1971–3 celebrating the power of stone, while Canadian artist Bill Vazan’s fish-eye panels entitled 6th Circle, completed in 1977, combine feelings of openness and enclosure.

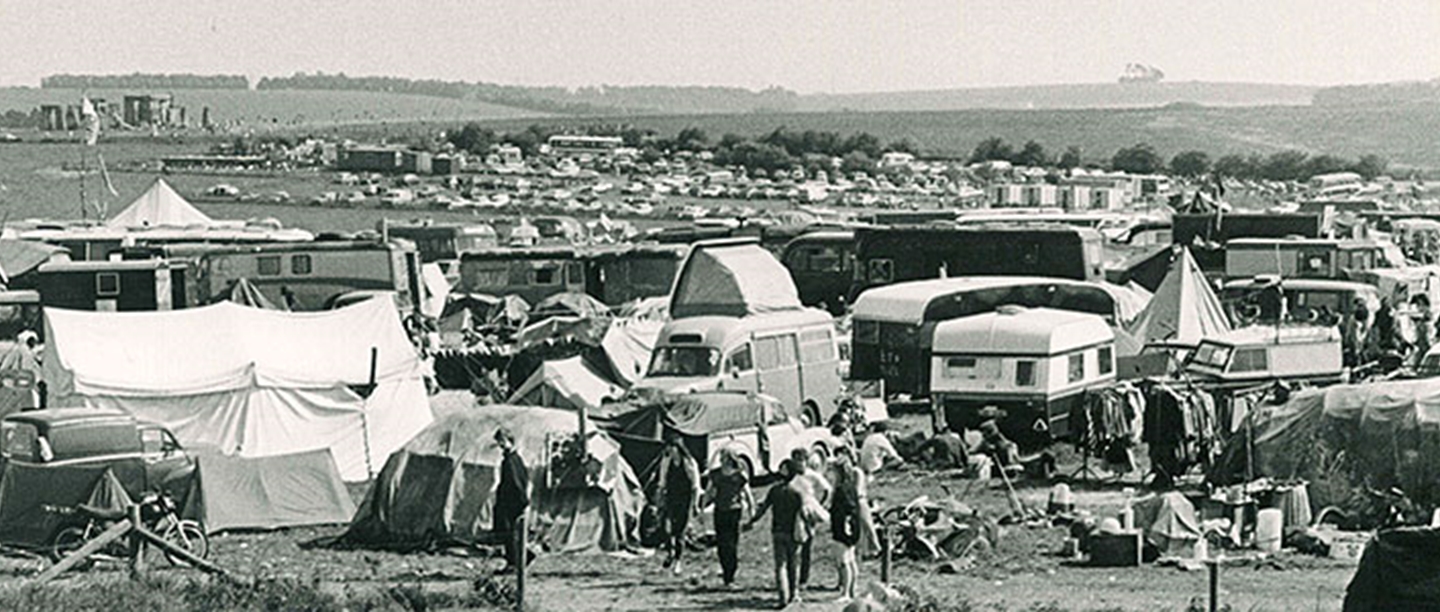

Music contributed much to the solstice celebrations at Stonehenge, and promoted free-spirited thinking through albums such as Stonedhenge by Ten Years After, released in 1968. In 1974 Wally Hope and others promoted a ‘Free Stoned Henge Festival’ to coincide with the summer solstice. The following year it drew far bigger crowds, thereby starting a tradition that lasted until 1984 and embedded Stonehenge deep into popular culture.

Find out more about how we are celebrating the Stonehenge 100 anniversary on our website.