© Popperfoto via Getty Images

Nightingale was born into a well off and well-connected family with landed estates in Derbyshire and Hampshire and a fortune originally derived from banking. She was named after the city of her birth, which her parents were visiting as part of their European ‘grand tour’.

She was educated at home, but only broadly, and chafed against the lack of opportunities – apart from marriage – for young women of her social class. On a visit to a community of Protestant deaconesses at Kaiserswerth, Germany, Nightingale felt a calling towards the care of the sick. She was impressed with the deaconesses’ devotion, though not with their standards of hygiene and nursing. The course of her life was set.

In 1853 Nightingale became the superintendent to the Establishment for Gentlewomen during Illness in Upper Harley Street, London. This was an unpaid post, with her father supplying her with an allowance. Her efficiency and drive impressed many, and she showed bravery and resourcefulness in assisting during the cholera outbreak in Soho in 1854.

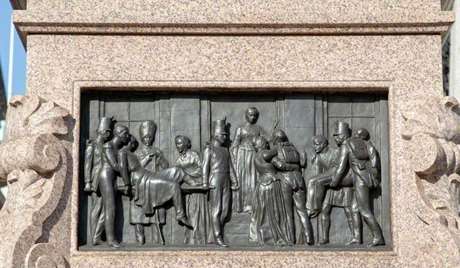

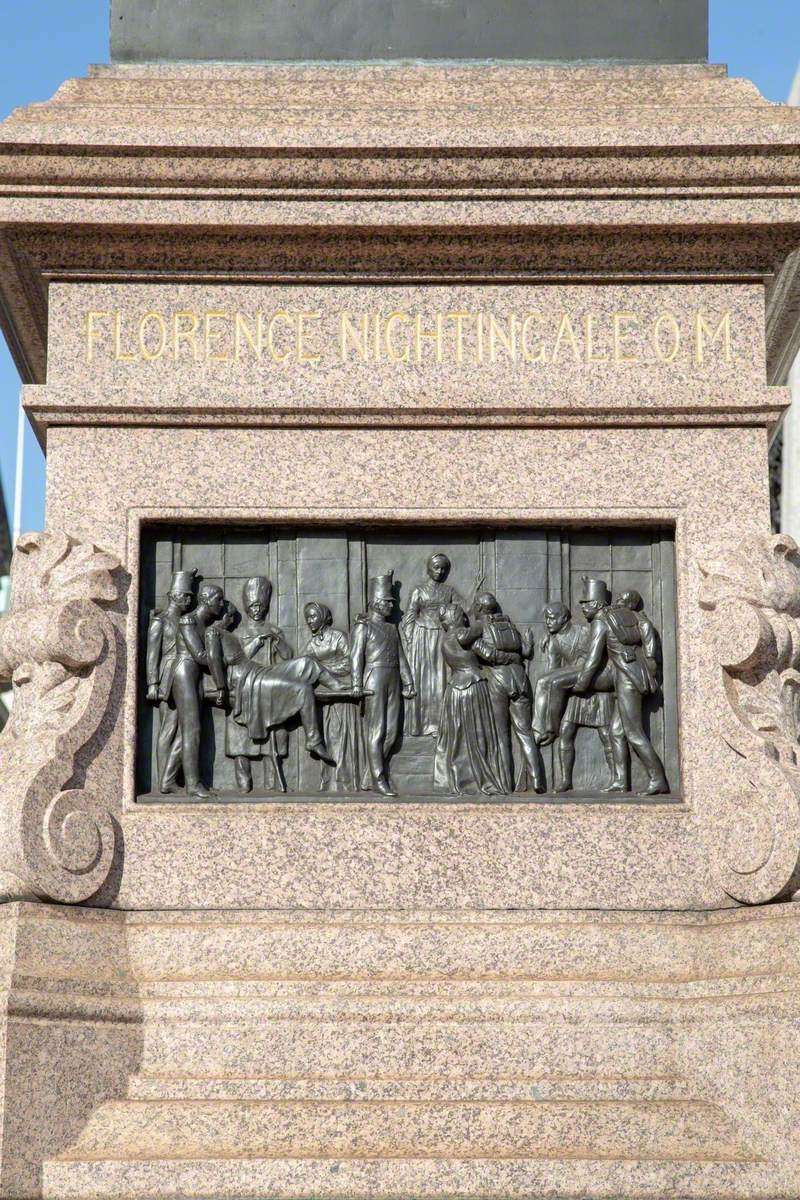

On a trip to Italy undertaken to overcome a depressive episode, Nightingale met and befriended Sidney Herbert (1810–61). By the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854 Herbert was Secretary of State for War, a connection which led to Nightingale being commissioned to take 38 nurses – 14 professionals and 24 from religious sisterhoods – to the military hospital at Scutari, in Turkey. Most of the nursing orderlies she managed there were, however, male.

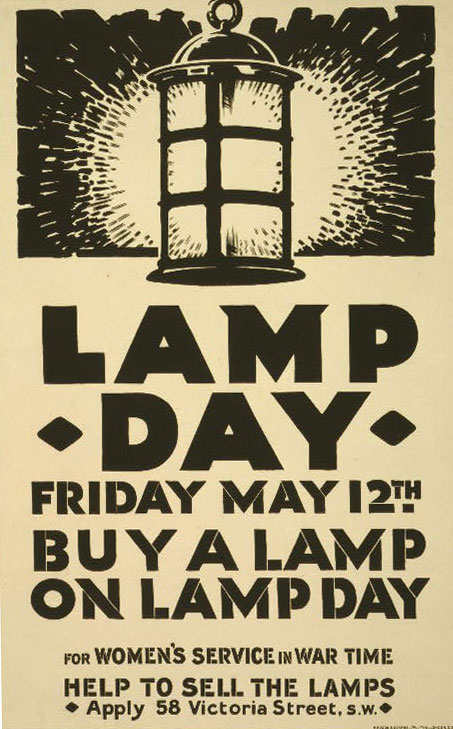

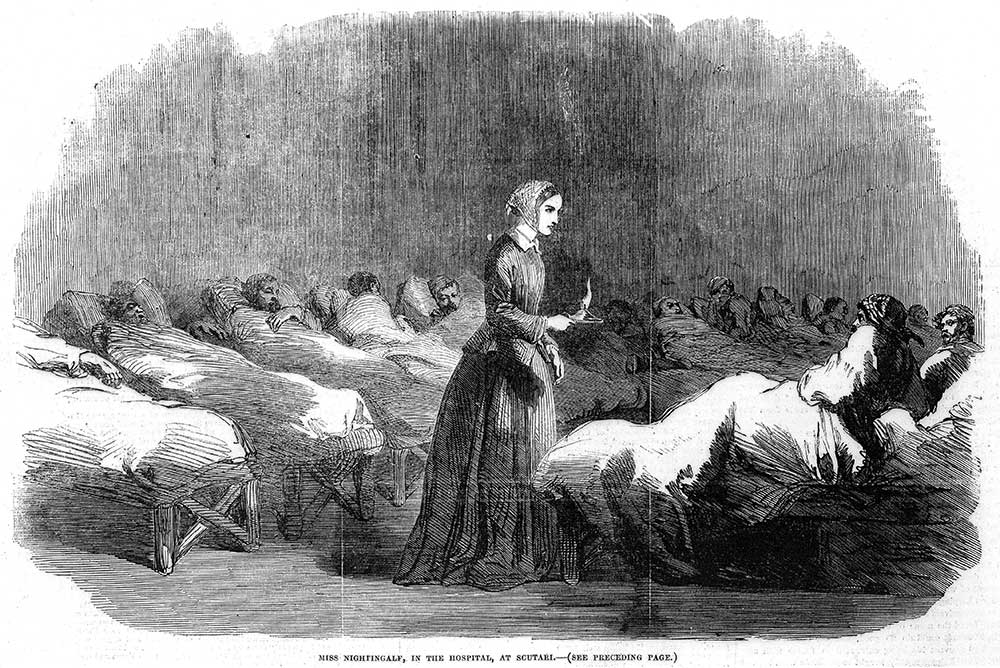

At Scutari, by rapidly implementing improvements in discipline, food provision and sanitation standards, Nightingale secured a fall in the hospital mortality rate from 42% in February 1855, to 2% four months later. The Times called her a ‘ministering angel’, and its reports of her nightly ward rounds spawned the nickname ‘The Lady with the Lamp’. A variant of this appeared in an 1857 poem by Longfellow, which further lauded her as ‘A noble type of good/Heroic womanhood’.

© Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Nightingale’s wider achievement was in raising the status and standard of nursing as a profession – previously, anyone could call themselves a nurse. Admirers, including many contacts from her early life, subscribed £50,000 to allow the foundation of the Nightingale School and Home for Nurses, which was established at St Thomas’s Hospital, London in 1860. In the same year she published Notes on Nursing, in which she observed simply that the purpose of nursing ‘is to put the patient in the best condition for nature to act upon him.’

Nightingale wrote much else – on subjects as varied as public health, religion and the enhancement of rights of women. Her collected works, published over recent years, run to 16 volumes. Her influence, especially in promoting hygiene, extended worldwide. Her later achievements included dramatic improvements in the mortality rate among soldiers in India, and the establishment of an army medical school at Chatham.

Nightingale’s reform drives were all informed by the recording and analysis of statistics – ‘the most important science in the whole world’, she believed. In this she was a pioneer, and also in her use of data visualisation: she was an early and enthusiastic user of pie charts. She was a member of the Royal Statistical Society and the London Epidemiological Society. In this she seems startlingly modern. Less so was her failure to support vaccination against smallpox, and she did not accept the germ theory of disease until quite late in life.

© Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Florence Nightingale spent much of the last two decades of her life as a housebound invalid, suffering from what may have been brucellosis. In 1907 she became the first woman admitted to the Order of Merit. She died at her home in South Street, Mayfair, at the age of 90. The site of the house is marked with a blue plaque.

Her first, very thorough, biography came out in 1913, and many more followed. Lytton Strachey’s chapter in Eminent Victorians (1918) was early to point out that her success rested on an iron will, and that it produced casualties – including, he believed, the early death of Sidney Herbert through overwork. But as a woman of that time, she had no other means of exercising influence than by putting pressure on the men who held power.

Florence Nightingale remains a prominent historical figure whose inner life continues to intrigue. She hated being painted or photographed, and yet her image, in her trademark nursing cap, has adorned stamps and banknotes. Her reach remains wide: as well as hospitals and hospital wards, a Dutch aircraft, a US Navy ship and an asteroid have been named after her.