Prelude to the Battle

1066 was a turbulent year for England. King Edward the Confessor died on 5 January leaving no direct heirs and the country threatened with invasion by two rival claimants, Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, and William, Duke of Normandy.

Edward entrusted the English throne to Earl Harold of Wessex, who was his brother-in-law and the commander of the royal army. Harold was consecrated king in Westminster Abbey, London, on 6 January, the day after Edward’s death.

In May, Earl Edwin of Mercia defeated an invasion of eastern England led by King Harold’s exiled brother Tostig, while Harold concentrated his forces along the south coast.

Following news of Hardrada’s Norwegian army landing near York in mid-September, Harold moved swiftly north, decisively defeating the allied forces of Harald Hardrada and Tostig at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September. A few days later the king heard that Duke William had landed at Pevensey in Sussex.

In a series of forced rides the English army returned south, pausing briefly in London to gather fresh troops before arriving opposite William’s forces at what is now Battle (7–8 miles from Hastings) on the evening of 13 October. By contemporary standards the opposing armies were substantial – modern scholars suggest that each had between 5,000 and 7,000 men.

The Battle of Hastings

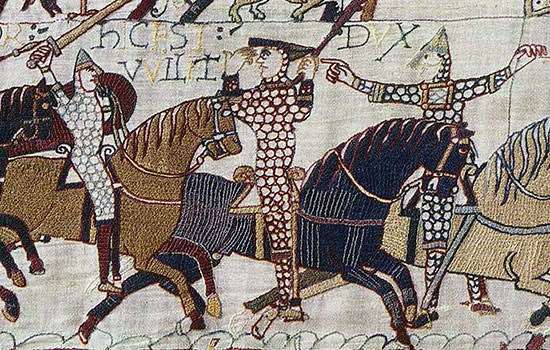

The principal sources for the Battle of Hastings are the Bayeux Tapestry and the chronicler William of Poitiers.[1] Between them they provide more information than for any other medieval battle, although many details remain unclear.

At daylight on 14 October Harold deployed his forces along the ridge now partly occupied by Battle Abbey. Opposite, on rising ground to the south, William ranged his army.

Both armies were equipped with similar armour and weapons, but the Norman archers also had powerful crossbows and the Norman army relied on a cavalry force of perhaps 2,000–3,000 knights and esquires.

The English forces travelled on horseback, but fought on foot. At their centre were the housecarls, the king’s retainers, with their fearsome battleaxes, perhaps the finest infantry in Europe.[2]

The Battle of Hastings was exceptionally long by medieval standards, lasting all day, an indication of how evenly matched the rival armies were. The English, protected by their ‘shield wall’, withstood repeated and bloody assaults up the hillside by Norman cavalry and archers.

Gradually the Normans gained the upper hand until in the last attack Harold was killed. Leaderless, the English finally gave way and fled. William assumed the throne of England, was crowned on Christmas Day 1066 and ruled until his death in 1087.

More about the Battle of HastingsThe foundation of Battle Abbey

The Benedictine abbey of Battle was founded and largely endowed by King William in about 1071. Dedicated to the Trinity, the Virgin and St Martin of Tours, it was established as a memorial to the dead of the battle and as atonement for the bloodshed of the Conquest. It was also a highly visible symbol of the piety, power and authority of the Norman rulers.

Despite the unsuitable location on top of a narrow, waterless ridge and objections from the first monks, William insisted that the high altar of the abbey church be placed to mark where Harold had been killed.[3] When the new church was consecrated in 1094 in the presence of William II (reigned 1087–1100) and the Archbishop of Canterbury, it was one of the richest religious houses in England.

Read more about the Abbey’s FoundationLife in the Abbey

Until its suppression in 1538 the abbey, like many other English monastic houses, played a central role in the spiritual, economic, agricultural and military life of the area. Its founding community came from Marmoutier in France. The Chronicle of Battle Abbey states that the Conqueror resolved that the founding community should be composed of 60 monks, but he intended that it would increase to 140, although it is not known if it ever reached this figure. The Black Death of 1348–9 reduced the community from 52 to 34 monks, a figure that remained fairly constant over the next century.[4]

The monks lived according to the Rule of St Benedict and divided their day into periods of prayer, reading and manual labour. They gathered in the church for 8 services a day and daily mass. A single surviving service book from the abbey provides important evidence of the saints honoured with feast days at the abbey. St Martin had a special place of honour.[5] The abbey's accounts record expenditure on images, crosses and vestments. Battle would have had a substantial library, but only 24 books are known to survive.[6]

Surplus produce from the abbey’s extensive estates sold on the open market was an important source of income.[7] The adjacent town of Battle owes its existence and growth to the abbey's patronage of its merchants, traders and craftsmen.[8] The varying fortunes of the abbey are reflected in its surviving architecture, with periods of prosperity leading to modernisations and rebuilding.

Battle Abbey had a number of very important privileges. It was exempt from visitation by the local bishop (the bishop of Chichester), and only the archbishop of Canterbury could intervene in the internal running of the monastery. Abbot Hamo of Offyngton (1364–83) was granted papal permission to use the mitre and other ornaments normally reserved for bishops; after this time the mitre appeared on the abbey’s coat of arms.[9] The abbots of Battle sat in the House of Lords and played a part in affairs of state, maintaining lodgings in London and Winchester, Hampshire, for this purpose.

During French raids in the Hundred Years War (1337–1453), the abbots organised local defences and provided food and clothing for refugees fleeing the coastal towns. In 1377 Abbot Hamo became famous for leading his forces in person in the successful defence of nearby Winchelsea.[10]

Read more about the Battle Monks’ LivesThe Suppression of Battle Abbey

Religious life continued to be observed into the 16th century, but Battle Abbey could not escape the destruction of the monasteries by Henry VIII. The official reason that monastic religious observances were moribund masked the reality that the king wanted the monastic lands and assets. The abbot and the 18 remaining monks of Battle surrendered to the king’s officials in May 1538. The abbey’s annual income was assessed at £880 and its plate was valued at over £300.[11]

Henry VIII gave the abbey and much of its land to his friend and master of the horse, Sir Anthony Browne. The church and parts of the cloister were demolished and the abbot’s lodging was adapted to serve as a country house.

Battle as a Country Estate

Despite profiting from the Suppression, Sir Anthony Browne had conservative religious views and in the late 16th and early 17th centuries Battle became an important centre of Catholic recusancy.[12]

In 1721 Browne's descendants sold the estate to Sir Thomas Webster. Apart from the period 1857–1901, when the Duke and Duchess of Cleveland owned the property,[13] it remained in the ownership of the Webster family until 1976 when it was acquired by the state.[14]

As in the case of many such estates, there were absentee owners, long periods of neglect and the sale of land to raise funds. Between 1810 and 1820, however, Sir Godfrey Vassall Webster repaired many of the buildings, as did the Clevelands later.

Since 1922 the abbot’s lodging has been leased to a school. Under state ownership there has been an extensive programme of building conservation with recording and archaeological excavations.[15]

About the Author

Jonathan Coad is a historian and archaeologist, and worked for many years as an Inspector of Ancient Monuments on the conservation and display of Battle Abbey and Battlefield. He is the author of the English Heritage Red Guide to the site.

Buy the guidebook to Battle Abbey and BattlefieldRead more about Battle Abbey and the 1066 Battlefield

DOWNLOAD A PLAN OF BATTLE ABBEY

More about 1066 and the Normans

-

1066 and the Norman Conquest

Find out much more about the Battle of Hastings and the events of 1066, and discover where to find some of the most spectacular castles and abbeys the Normans built across England.

-

Battle Abbey and 1066 Battlefield: History and Stories

Use this hub page to find links to a wealth of information about the Battle of Hastings, the battlefield itself and Battle Abbey.

-

What happened at the Battle of Hastings?

At dawn on Saturday 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Read what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

Where did the Battle of Hastings happen?

Was Battle Abbey built ‘on the very spot’ where King Harold fell, or was the Battle of Hastings actually fought elsewhere?

-

William the Conqueror and Battle Abbey

Discover the reasons behind William I’s decision to found an abbey on the site of his victory over King Harold.

-

‘Be Mery All’: The Battle Abbey Carol

One of the pieces of music visitors to the abbey will hear is a late medieval carol. Find out the story behind it and its new musical setting.