Location

Donnington Castle sits on a hilltop just north of Newbury in Berkshire. The site overlooks the old road running south–north from Southampton to Oxford, which is still called Oxford Road as it runs through Donnington. It also overlooks the main road from London to Bristol and the west, now better known as the Bath Road or A4, which was a significant trade route at the time.

With the king’s headquarters in Oxford, and Parliament’s in London, the castle’s position commanding both these important national routes made it a strategic location during the Civil War.

Among the major battles early in the Civil War was the First Battle of Newbury in September 1643, fought on the opposite side of the Kennet valley from the castle, across Wash Common and the surrounding area.

READ MORE ABOUT THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR

Strengthening the defences

At the First Battle of Newbury, the Royalists failed to prevent a large Parliamentary army returning to London. Shortly afterwards, Lieutenant-Colonel John Boys was sent to Donnington to hold the castle for the king, with 200 foot (infantry) of the Earl Rivers regiment, along with 25 horse (cavalry) and four cannon.

John Boys set about strengthening Donnington Castle’s outdated defences by building a very substantial earthwork around it, designed to fortify the hilltop and defend it against cannon fire.

This was a major engineering project and cost £1,000 (the equivalent of well over £100,000 today). It was arranged in the military style of the period with ‘star’ points projecting in differing directions to gain command of the surrounding area. The largest, now collapsed, was a pointed projection towards Newbury. While it is now difficult to make sense of the shapes from the ground, the earthworks can be seen more clearly in aerial views.

Sir John Boys (1607–64)

John Boys was born in Kent in 1607, and inherited the family estate at Bonnington in Goodnestone. He was already a soldier in the 1630s, and in 1640 served as a captain in the army of Charles I against the Scots. By November 1642 he was a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royalist regiment of John Savage, Earl Rivers.

He was appointed governor of Donnington Castle shortly after the First Battle of Newbury, and made responsible for organising its defence. He began by arranging the construction of the substantial earthworks which proved so important in withstanding assault. For leading the defence, he was knighted by the king in 1644, and promoted to full Colonel.

Following the surrender of the castle in April 1646, Boys made short trips to the Netherlands but spent much of his time in Kent, where he played a leading role in the failed county rising of 1648. He suffered brief periods of imprisonment and fines, but survived through the Commonwealth (1649–60) and was among those active in 1660 in preparing for and supporting the Restoration of King Charles II.

Sir John Boys died in October 1664 and was buried at Goodnestone, Kent. His memorial states that his ‘military praises will flourish in our annals as laurels and palms to overspread his grave’. It calls Donnington Castle ‘a noble monument to his fame’ for ‘the honour of its gallant defender’.

The siege begins

The siege of Donnington Castle began in July 1644, when Lieutenant-General John Middleton was sent to Donnington with 3,000 troops, to take it for Parliament. He deployed his whole force on 31 July, making the first of many demands from Parliament for the surrender of the castle.

Sir – I demand you to render to me Donnington Castle (of which you are now Governor) for the use of the King and Parliament. If you please to entertain a present treaty you shall have honourable terms. My desire to spare blood makes me propose this. I desire your present answer.

John Middleton. July 31, 1644.

Back came the reply:

Sir, I am entrusted by His Majesty’s express command, and have not yet learned to obey any other than my Sovereign. To spare blood, you may do as you please, but as for myself and those that are here with me, we are fully resolved to venture ours in maintaining what we are entrusted with, which is the answer of

Your servant John Boys. Donnington Castle, July 31, 1644.

When Middleton’s demand was rejected, he launched a full assault with scaling ladders, but it failed, with heavy losses. Then he left to continue his army’s journey to the west, leaving the castle to be dealt with by local forces.

The siege was to last for 20 months, but it was rarely a total blockade: in quieter times, Boys even held a market for provisions at the castle.

The attacking armies

Colonel Jeremy Horton, with Parliamentary forces from Abingdon and Reading, continued the siege in September 1644 by setting up a battery of cannon at the bottom of the hill on the Newbury (south) side of the castle. It is said that in 12 days of continual shooting he demolished three of the castle’s towers and part of the curtain wall.

Then, after his demand for the surrender of the castle was rejected, he moved his cannon to the opposite (Snelsmore) side of the castle and continued. Boys’s forces staged a night attack on their siege-works, killing many soldiers and capturing arms and ammunition. Nevertheless, the bombardment continued. The Earl of Clarendon wrote in his history of the Civil War that over 1,000 shot were fired by cannon at the castle in just 19 days.

The barrage only stopped when the Royalist army arrived in Newbury with King Charles in October 1644, and started establishing defences to the north of the town. The king knighted John Boys on 22 October, for his defence of the castle.

The Second Battle of Newbury

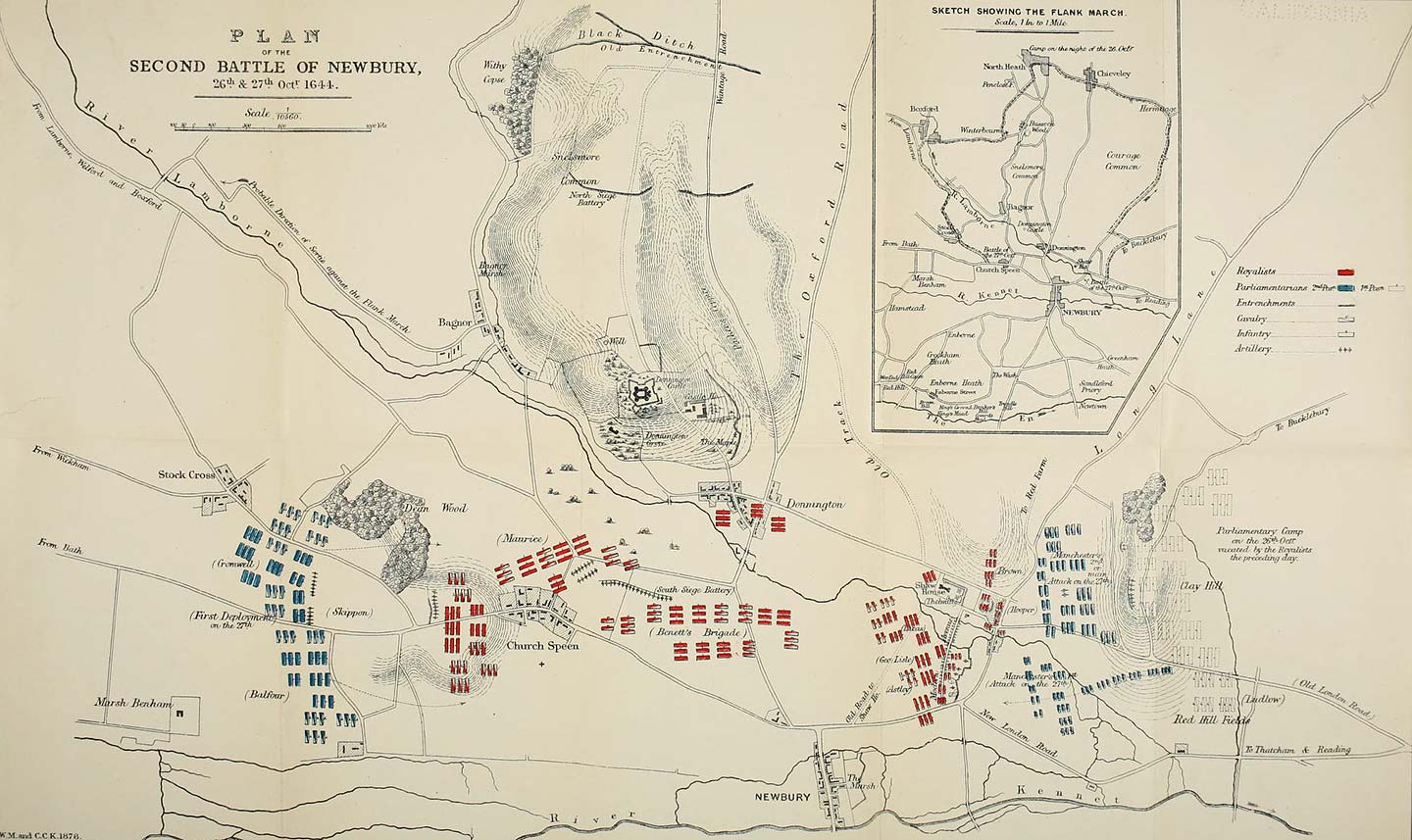

The Second Battle of Newbury took place on 27 October 1644, with a heavily outnumbered Royalist army led by Charles I in person, facing a Parliamentary army led by the Earl of Manchester and Sir William Waller.

The Royalists took positions across the north of Newbury from Shaw to Speen, including a fortified Shaw House. The Parliamentary commanders decided to split their army to attack the Royalists from both east and west, but the dominant position of Donnington Castle meant that a long ‘flanking march’ to the north was needed to get everyone in position.

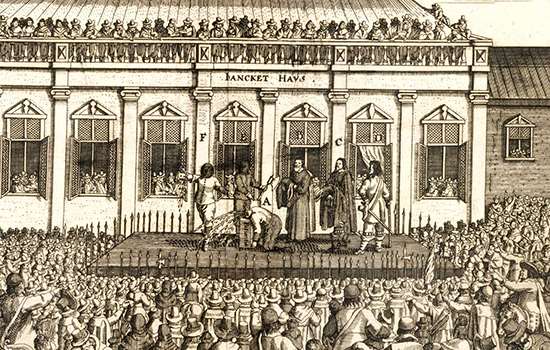

Fierce fighting took place, and in spite of a strong defence from Shaw House, King Charles narrowly avoided capture and the Royalist army was in a vulnerable position at the end of the day. They escaped overnight, leaving the wounded and artillery at Donnington Castle, to avoid slowing them down and making them more vulnerable to attack. Also left were items of particular importance to the king, including his crown and the Great Seal.

The next day Sir William Waller drew up the whole Parliamentary army before the badly damaged Donnington Castle, and demanded it should surrender; otherwise, he said, not one stone would be left upon another. Sir John Boys replied that if so, he was not bound to repair it. A more conciliatory demand met with a similar rebuff. Then the Parliamentary forces staged an assault, but the officer in command was killed along with several soldiers, and it petered out.

Less than a fortnight after the battle, on 9 November 1644, King Charles returned with additional forces to relieve the castle. There were skirmishes between two large armies, which this time held back from a full-scale battle.

Charles stayed in the castle overnight while he recovered artillery and his abandoned items. Parliamentary commanders argued about whether to attack, with Oliver Cromwell urging action and Manchester in favour of caution. This was the source of much division on the Parliamentary side, one of the factors which led to the rise of Cromwell.

That the ruined castle at Donnington then survived in Royalist hands from November 1644 until 1646 is partly explained by events elsewhere in the Civil War. Over the period, the king’s position deteriorated badly.

Raids and sallies

During the siege, there were many sallies against the castle’s attackers, when the defenders broke out from behind their earthwork and attacked the besiegers. They even built a hidden exit from their earthwork, so that they could ambush the besiegers unexpectedly.

Longer-range raids are also documented. For example, Sir John Boys (whose home was in Kent) led a series of raids to attack the (Parliamentary) Kentish Regiment at distances of six to ten miles from the castle.

According to one source, a party of about 100 foot from Donnington Castle ‘passed hedge and ditch’ as they headed south to fall on the Kentish Regiment at Burghclere (across the county boundary into Hampshire) in the dead of night. They came away with about 80 horses, weapons and other ‘pillage’.

In response to this attack, the Kentish Regiment moved its base west to Woodhay for safety, and this time Boys organised a party of 120 foot to attack them, prepared with axes and hammers to break through doors, and ‘granades’ to throw in through windows. They fell on the Kentish Regiment in four houses at East or West Woodhay, and again took horses, weapons and plunder, as well as prisoners.

The Kentish Regiment then withdrew further west to ‘Balsome Howse’ (Balsdon House), near Inkpen, which had a moat for additional security. They were now ten miles from the castle, but Boys borrowed Royalist cavalry from Wallingford and joined them with his foot for the attack. The Kentish Regiment was confident in the house’s defences, and the attack caught them by surprise: ‘for as they cocksure slept without keeping guard or sentinels, the Royalists came unexpectedly upon them, broke up their gates, and surprised them.’

Surrender

In the autumn of 1645, after a key role in taking Basing House in Hampshire, Colonel John Dalbier was sent to blockade Donnington Castle and take it, arriving in Newbury in November. Boys had set fire to much nearby property, to reduce the opportunities for the attackers to use it both as cover and as accommodation over the coming months.

Little progress was made in the siege during a stormy winter, and in the face of sallies from the defenders, but in March 1646 Dalbier brought up a heavy mortar, and it very quickly inflicted heavy damage on the body of the castle and its remaining defences.

The position of the defenders became impossible, with no hope of relief, and the attackers allowed them to send officers to King Charles I at Oxford, to seek permission to surrender. The reply was that they should get the best agreement they could. The terms of surrender for the castle were negotiated on 30 March 1646, in a field still known as Dalbier’s Mead, just north of Donnington Castle House.

The terms were signed by the two commanders and by three officers on each side: for the castle, Colonel Boys, with Major Bennet, Captain Osborn and Captain Gregory; for the besiegers, Colonel Dalbier (‘Dulbier’), Major Rynes and Major Collingwood. The castle surrendered on 1 April 1646.

As noted at the time, the garrison marched out with flags flying:

The castilians were to march away to Wallingford with bag and baggage, muskets charged and primed, match in cock, bullet in mouth, drums beating, and colours flying; every man taking with him as much ammunition as he could carry: as honourable conditions as could be given. In fine, thus was Donnington Castle surrendered.

By David Peacock

Related content

-

Visit Donnington Castle

The striking twin-towered 14th-century gatehouse of this castle, later the focus of a Civil War siege and battle, survives amid impressive earthworks.

-

History of Donnington Castle

Read a full history of Donnington Castle, built in the late 14th century more as luxury residence than fortress, but pressed into service during the English Civil War.

-

Donnington Castle’s female keeper

Discover how Elizabethan noblewoman Lady Elizabeth Russell was prepared to take up arms to defend her post as keeper of Donnington Castle.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Find out more about how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

Selected sources

Margaret Wood (Mrs EG Kaines-Thomas), Donnington Castle (London, 1964)

Walter Money, A Guide to Donnington Castle, near Newbury, Berks (3rd edn, Newbury, 1917)

Walter Money, The First and Second Battles of Newbury and the Siege of Donnington Castle (2nd edn, Newbury, 1884)

Edward, Earl of Clarendon, History of the Rebellion, ed. W Dunn Macray, 6 vols (Oxford, 1888; volume 3 covers the siege of Donnington)

Edward Walker, Historical Collections of Several Important Transactions relating to the Late Rebellion and Civil Wars of England… (London, 1707)

James Heath, A Brief Chronicle of the late Intestine Warr in the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland... (London, 1676)