King John’s Disastrous Reign

From the early years of his reign King John had become a hated figure among many English barons. This was initially because of military failures that resulted in the loss of Normandy and Anjou to the French king, Philip II, in 1204, and the imposition of heavy taxes in order to fund new military campaigns to try to recover them. King John even resorted to the extortion of money by questionable means.

The Church received the same treatment. When in 1207 King John refused the pope’s candidate for the Archbishop of Canterbury, he was excommunicated and placed in interdict (a sentence that forbade a person or persons from receiving church privileges). Restrictions on Christian worship and ceremonies were placed on everyone in his kingdom. Six years later, King John made a humiliating climbdown to the pope’s will, and paid homage to him, an act seen by many subjects as subjugation to a foreign power.

Then in 1214 King John’s last military campaign to recover his lost lands ended in defeat, again. In England, this was the last straw for a growing group of dissatisfied barons.

Magna Carta

In spring 1215, the barons and King John discussed a series of potential reforms and rights but made no real progress. In early May, the barons openly defied the king and took up arms against him, laying siege to the royal castle at Northampton. On 17 May, they captured London, including King John’s treasury and exchequer, forcing the unwilling king to consider their demands and arrange peace talks.

The king and barons met at Runnymede on 10 June 1215 where the ‘Articles of the Barons’, a document that laid out the barons’ demands for political reform, was presented. Five days later, King John put his seal to a document that enshrined these articles, which placed limits on royal power. The charter was to become known as Magna Carta.

Four days after the sealing of the charter, the barons renewed their allegiance to the king, and subsequently some efforts were made on implementing reform. But in reality, neither side trusted the other and in early September, negotiations ended. King John gathered forces on the south coast at Sandwich and Dover and began to march on London. He was blocked by the castle guarding the crossing of the Medway at Rochester, and a long siege followed. John took the castle but made no further progress towards London.

King John’s Campaign

Instead, King John began a campaign to capture rebel-held castles and territory, fighting up through the Midlands and into the North as far as Berwick-upon-Tweed, and back down to East Anglia. It went well for King John, so much so that in the spring of 1216, the barons sought help from Louis of France, heir to the French throne. He arrived with an army at Sandwich on the coast of Kent in May 1216.

The course of the war then tilted in favour of the rebels. John retreated into the west country and Louis was proclaimed king in London by the barons, though not crowned. War raged in the summer of 1216 as Louis and the English rebels began to make progress. Dover Castle was a key place to capture, as it guarded the surest link to France for bringing in men and supplies. It was a formidable fortress, with a strong garrison of knights and men at arms under the command of Hubert de Burgh, Justiciar of England (John’s principal minister), a warrior of great experience.

Dover Under Siege

The first siege began in May 1216. There is a surviving written account by an unknown eyewitness, known to scholars as the Anonymous of Béthune, which enables us to understand the basic sequence of the two sieges. The first attack came from the north towards the main gate of the castle, which was protected by a barbican (a fortified enclosure outside the gate).

The attacking force bombarded the barbican with siege engines, and undermined its rampart, successfully capturing it. Then Louis set his engines and miners to work on the main gate of the castle, eventually bringing down the eastern tower, its collapse creating a steep ramp of rubble for his assault force to climb and storm the fortress. Despite fierce resistance from Hubert’s men, Louis’ assault force broke into the outer bailey. A bloody struggle followed but Huberts’s men gradually killed Louis’ men or drove them back out through the breach in the castle wall.

Despite this setback, Louis maintained the siege into the autumn, and the alliance with the rebels maintained the upper hand across over half of the kingdom. At Dover, Hubert’s engineers quickly repaired their defences, creating a strong barricade across the broken castle wall with wooden beams, rubble and earth.

Read more about medieval siege tactics and weaponryTurning of the Tide

In September, King John was far from subdued and began a new military campaign, heading down the Thames valley and up into East Anglia. But in October King John contracted dysentery and died at Newark on the 18th. Ten days later, his nine-year old son was crowned as King Henry III in Gloucester Cathedral and came under the watchful guidance and regency of the veteran knight, William Marshal.

John’s death and his son’s accession changed everything. How could the rebels hold any grudge against a young boy king? The source of their grievances was dead. Nevertheless, the winter was tense, as many waited to see how the French and diehard rebels progressed early in 1217. There was, however, a slow return of baronial support to the young king’s side.

At Dover, Louis had urged the garrison to surrender after John’s death, but Hubert de Burgh refused, vowing to hold the castle for the new young king. There followed a period of uneasy truce at the castle, though this was not well observed, with English forces in the surrounding area under King John’s bastard son, Oliver, and a minor lord called William of Cassingham, harrying the French and baronial forces.

The Second Siege

The trickle of returning support for the young king became a flow after 20 May when a strong force of French and rebel soldiers was defeated at Lincoln. Meanwhile, Louis had begun a second siege of Dover Castle on 12 May 1217, battering the walls with siege engines that included a trebuchet – the first recorded instance of such an engine in England – but the garrison held firm once more.

Louis remained on the south coast, increasingly dependent on reinforcements from France. He had employed the notorious pirate, Eustace the Monk, to bring a fleet of reinforcements and supplies across the Strait of Dover. This fleet was intercepted and destroyed by a fleet assembled by Hubert de Burgh, in a battle off the coast near Sandwich, in August 1217.

The rebels’ cause was lost and there was no longer any hope of victory. Accordingly, peace negotiations began and were concluded by the signing of the Treaty of Lambeth on 11 September 1217. Louis returned to France and the reign of King John’s son, Henry III, resumed in a time of peace.

By Paul Pattison

Explore more

-

History of Dover Castle

Learn about the long history of the castle, from its likely origins as an Iron Age hillfort, through its development as a great fortress, to its secret role in the Cold War.

-

Medieval Siege Warfare

Explore some of the artillery and devices and the complex strategies for attack and defence used in medieval siege warfare before gunpowder weapons were invented.

-

The Angevin Empire

King Henry II, who built Dover Castle’s great tower, also created the largest European empire of his age, stretching at its height from Scotland to the Pyrenees.

-

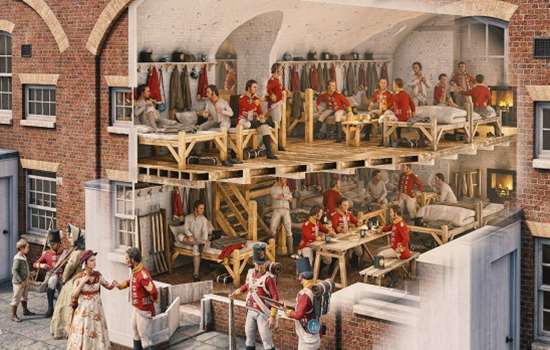

Dover Castle: The Georgian Fortress

Read about Dover Castle’s transformation into a permanent barracks and artillery fortress in the Georgian era, a role that continued into modern times.