The Discovery

Leslie Armstrong discovered the Goddess while excavating Pit 15 at Grime’s Graves. He found it alongside a group of ‘ritual objects’ – several other chalk carvings including a phallus and cup, three flint nodules arranged to resemble a phallus, and seven antler picks on an altar.

In 1951, Armstrong recounted the discovery in his site notebook:

The Goddess was uncovered on the S.W. side of the pit, at the right hand side of Gallery 7, in an upright position resting upon a flat slab of chalk … Removal of the remaining filling of the shaft revealed upon the floor of the pit, opposite the Goddess, an ogive shaped platform, believed to be an altar, constructed of blocks of mined flint packed closely together with its apex pointing towards the Goddess.

Opposite where the Goddess was found, Armstrong described traces of wood ash and charcoal, which he believes may have been from a small fire that could have been part of a ritual. His belief was that this pit was less productive than others on the site and the Goddess, alongside the phallus, may have been placed as ritual objects by the miners in order to appeal for a more abundant seam of flint.

The Goddess

The Grime’s Graves Goddess, currently held in the collection of the British Museum, is carved from a round chalk cobble, 11.43cm in height by 8.89cm in width. She is well-rounded, with her arms extended on large prominent breasts and thighs. She appears to be kneeling and may possibly be pregnant. She has crudely carved facial features and an enigmatic smile.

Explore a 3D model of the Goddess below. Click the play button and use your cursor or touch screen to rotate the object and zoom in.

Model created by the British Museum.

Controversial Origins

Due to the unusual circumstances around the discovery of the Goddess by Armstrong, many have questioned the true origins of the figurine. We have no photos of the actual discovery, only a grainy image of the accompanying ritual ‘phallus group’. According to the available accounts prior to the discovery of the Goddess, Armstrong, who had been implicated in other fraudulent finds, had sent away the other excavators and had been alone in the pit.

A further dramatic twist to the events happened shortly after the Goddess’s discovery. Armstrong gave the figurine and the phallus to his fiancée, Ethel Rudkin, for safe keeping. An argument ensued when Rudkin, who was a sculptress as well as a folklorist and archaeologist, proceeded to then carve a copy of the Goddess. This enraged Armstrong, leading to a bitter argument, ending their relationship, and forever adding to the controversy over the true origins of the figurine.

In 1983, the then 91-year-old Ethel Rudkin contacted Kevin Leahy of Scunthorpe Museum to donate her collection of antiquities. She showed him the chalk copy of the Goddess and a chalk cup, saying that these objects had brought her great sadness but that she had never been able to destroy them. She recounted that when she accompanied Armstrong to Grimes Graves in 1939, that he had behaved strangely at the time and refused to allow her into the workings. This was odd as she was the only other experienced excavator present.

Rudkin offered the copy she had made to Leahy for Scunthorpe Museum, but when he was not able to take it and suggested donating it to the British Museum instead, Rudkin demanded the Goddess copy returned and it was never seen again! It should be noted that no photos of the Goddess copy exist, and Leahy recalled that it was only similar in a general sense – but not alike in detail – to the ‘real’ figurine now held in the British Museum.

Real or Fake?

The mines at Grime’s Graves are known to date from about 4,500 years ago, during the late Neolithic period. The problem with the Grime’s Graves Goddess is that there are no similar figurines from this period. The art of the late Neolithic is largely geometric or abstract, and human figurines have rarely been found.

Armstrong was convinced of an earlier origin for the flint mining at Grime’s Graves, stretching back into the Palaeolithic possibly over 50,000 years ago. The Grime’s Graves Goddess is reminiscent of European Palaeolithic ‘Venus’ figures or carvings.

Is the Goddess a fake? The obvious parallel with Palaeolithic carvings, as well as the copy carved by Rudkin, have led to suspicions that the Goddess was planted, perhaps as a hoax or to support Armstrong’s theories that mining began here before the Neolithic period. Would Armstrong have risked faking the object himself to support his theories? Unless more evidence comes to light we may never know the truth, but it is generally believed that Armstrong was probably not the forger, but rather the victim of a forgery.

Interestingly, during excavations of another mine shaft in 1971 a similar platform was found with the remains of a small hearth, flint flakes, and the remains of decorated pottery (Grooved Ware) bowls. ‘Closing deposits’ and offerings have been found throughout the mines, suggesting that even if the origin of the Goddess is questionable, rituals were indeed part of the mining process at Grime’s Graves.

The ongoing mystery of the Goddess means she retains an enigmatic aura – perhaps a metaphor for possible future discoveries at Grime’s Graves!

By Jennifer Wexler

Header image: The Grime’s Graves Goddess © Trustees of the British Museum

Explore More

-

History of Grime’s Graves

Read more about the history of Grime’s Graves, which has seen hundreds of years of activity by Neolithic flint miners.

-

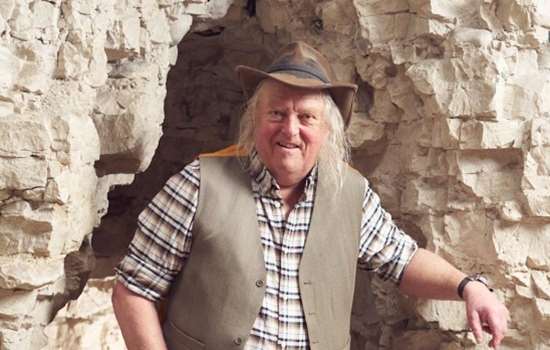

Grimes Graves Audio Guide

In this audio tour of the site archaeologist Phil Harding and English Heritage historian Dr Jennifer Wexler explore the lunar-like landscape of Grime’s Graves.

-

Collection Discoveries

Discover some of the objects found at Grime’s Graves including a range of skilfully worked (or ‘knapped’) tools, demonstrating the many uses and importance of flint during prehistory.

-

Ritual Mysteries

Intriguing finds from many of the pits at Grime’s Graves suggest that mysterious rituals accompanied the everyday task of mining. Read more about these discoveries here.