The abbey and its patrons

During the 12th century, the patronage of powerful and wealthy local families transformed Haughmond Abbey from humble beginnings into a prosperous religious house and one of the largest landowners in Shropshire. The close bonds established between the canons and the abbey’s benefactors lasted for the next 400 years.

Benefactors paid for the foundation or upkeep of a religious establishment as an indication of their own status and wealth. In turn the abbey looked after their souls, provided burial for the benefactors and their family members, maintained their tombs, and prayed for them. The relationship between the abbey and its patrons provided security and status for both.

Lay people were buried at Haughmond throughout the life of the monastery. Forty-one lay people who may have been buried there are mentioned in surviving documents, with a further five names appearing on burial monuments.

Excavations at Haughmond in the 1970s, centred on the cloister and the southern part of the nave of the church, found numerous intact burials as well as disturbed pieces of grave slabs and stone coffins. The church and cloister were common locations for the burial of important benefactors and prominent members of the abbey community at monasteries across the country. It is likely that there were more lay burials in the unexcavated parts of the site.

Female burials at Haughmond

Fourteen women are named in the abbey’s cartulary as having been buried at Haughmond. We can trace the story of the abbey and its patrons from the 13th century to the Dissolution through the burials of three of these women in particular, whose monuments survive. One can be seen in the chapter house, while the other two are now beneath the turf to protect them.

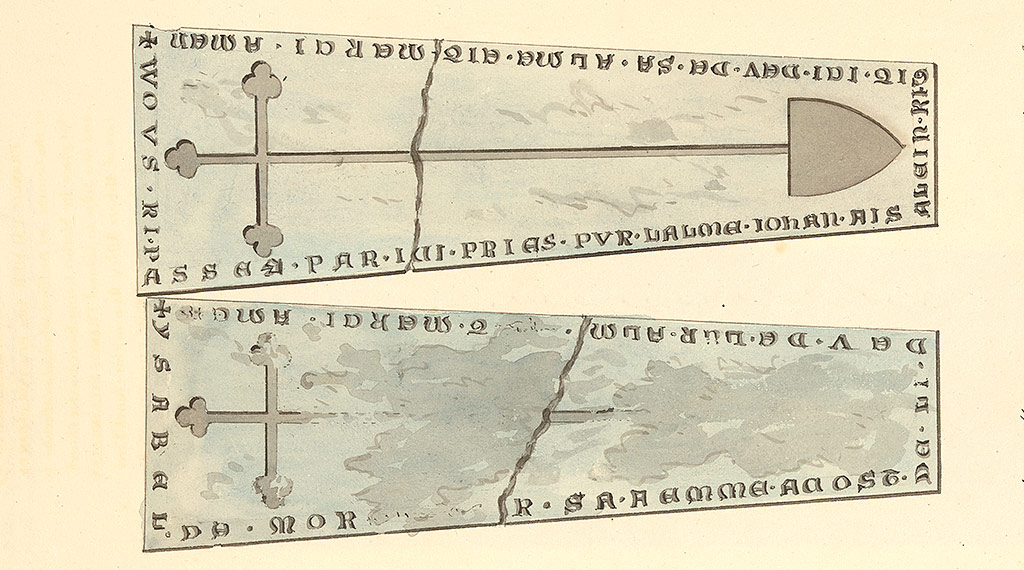

Isabel de Mortimer and her husband, John FitzAlan, were Haughmond’s principal patrons in the mid 13th century. They were laid to rest in the holiest and most significant location for burials – at the east end of the church, where Mass was celebrated – in recognition of their generosity.

Their grave slabs were found in fragments in the ruined church in the early 19th century and reset close to their original location – possibly in a chapel south of the presbytery. They have since been grassed over.

Olympias de Say of Stokesay died about 1210 and was buried under an elegant grave slab, decorated with long-stemmed crosses. Her broken grave slab was found in disturbed ground in the north cloister walk and is now in the chapter house.

The de Say family moved into a more central position in the politics of the Welsh Marches after the FitzAlans inherited earldoms in southern England and transferred their interests there. The de Says became one of the abbey’s two major donor families in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The latest monument for a woman found at Haughmond is the decorative slab commemorating Ankaret Mynde (d.1529). Hers was probably one of the last lay burials at Haughmond before the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The name Ankaret is an English variant of the Welsh name Angharad. Her mother, also Ankaret, was descended from one of the ancient royal families of Gwynedd and her father was one of the Leightons, a landowning gentry family of Church Stretton.

Ankaret had married Richard Mynde of Oswestry, a member of a minor gentry family. We don’t know if Richard had a coat of arms, which may explain the blank coat of arms at the top left on her grave slab, opposing her father’s arms on the right. He may have been a merchant. By the late medieval period the new mercantile elite were able to support abbeys financially, to the extent that would allow for their family members to be buried within the church.

This slab is in its original location, in the south-west corner of the nave, but has been reburied to protect it.

Images of female saints

In the 14th century, the canons added eight sculptures of popular saints and other significant religious people to the entrance front of their chapter house. This was the room where the canons met daily, and the monastery’s most sacred space after the church. Three of these sculptures depict female saints: St Catherine of Alexandria and St Margaret of Antioch – the two most popular female figures in the western Church after the Virgin Mary – and a local saint, Winefride (or Winifred).

Female saints became very popular in the late medieval period. As well as providing exemplars of ideal female behaviour, they were figures to whom women (and men) could turn in their prayers for protection and support. The martyred virgin saints depicted at Haughmond had their individual significances. Catherine was believed to be a powerful intercessor between Christ and those who invoked her, as well as a model of perfect womanhood; Margaret was the patron saint of childbirth and was also believed to intercede with God on one’s behalf.

The relics of Winefride had been removed from Wales to Shrewsbury Abbey, a few miles from Haughmond, in the 12th century. Many pilgrims visited her shrine there in the hope of securing her aid and achieving miraculous cures, boosting Shrewsbury Abbey’s finances in the process.

The depictions of these three saints indicate the high status of women in medieval Christianity. Although women’s roles then were very different from what they are today, they nevertheless had status and agency within the medieval church.

Writings about women

A further indication of a connection between Haughmond Abbey and medieval women is the possibility that key works of the 13th century discussing female saints and religious women were written there. These works are the Katherine Group, a set of five texts dealing with female saints including St Catherine of Alexandria and St Margaret of Antioch; and Ancrene Wisse, a book of instruction for women who lived as anchorites (religious recluses).

These texts were all written in the dialect specific to the part of the west Midlands near the Welsh border. It has been suggested that, as Haughmond was a major monastery in this area, its canons may have produced these works in its scriptorium, or writing room.

Image: The enclosure of an anchoress by a bishop, depicted in an early 15th-century manuscript

© The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Sacred spaces

The primary audience for the sacred imagery on the chapter house façade would have been the canons of Haughmond. St Catherine and St Margaret were widely depicted in medieval art – often together – and were venerated across England and beyond. It is unsurprising that they are depicted at Haughmond, together with a local female virgin saint.

Yet could there have been a female audience for the saints’ images too? Women from benefactor families would have visited Haughmond to attend funerals, and to visit the burial monuments of family members in the church and cloister to pray for them. Though lay people’s access to the cloister would have been very limited, they may have walked past the chapter house when moving between the church and the abbey’s guesthouse. On special occasions elite laypeople may also have been granted privileged access to the chapter house.

Medieval women shared an especial affinity with female saints, seeing their own tribulations in the saints’ lives and sufferings. The prominent presence of these three female saints on Haughmond’s chapter house is a reminder that the medieval faithful turned to the ‘holy company of heaven’ in the hope of securing salvation.

Cameron Moffett

Curator of Collections (West Midlands)

Related content

-

Visit Haughmond Abbey

The extensive remains of Haughmond Abbey include the abbot’s quarters and the chapter house, richly bedecked with 12th- and 14th-century carving and statuary.

-

History of Haughmond Abbey

Discover how over the course of the 12th century a small religious community at Haughmond was transformed into a great Augustinian monastery.

-

Women in male monasteries: an illicit presence?

Strict rules were in place to ensure that monks had minimal contact with women in medieval monasteries. But could they even have functioned without women?

-

ABBEYS AND PRIORIES

Learn about England’s medieval monasteries and uncover the stories of those who lived, worked and prayed in them.