Divine Retribution at the Jewel Tower, Westminster

How the 14th-century monks of Westminster Abbey interpreted the ‘wretched death’ of their hated next-door neighbour, the Keeper of the Palace of Westminster, as celestially ordained.

HIGH SECURITY

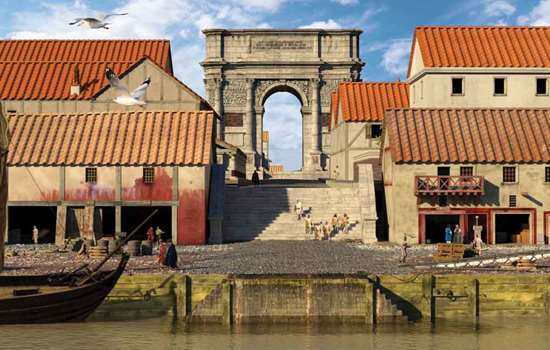

The Jewel Tower, a 14th-century addition to the Palace of Westminster in London, was built in 1365–6 to house the precious jewels, plate and textiles belonging to the household of Edward III (r.1327–77).

Such a high-security purpose required a secluded location, and the new structure, which had its own moat – vital for security – was certainly given that. It was separated from the royal apartments of the Privy Palace by a small royal garden, and even further removed from the more accessible law courts and Exchequer in and around Westminster Hall.

LAND GRAB

This presented a problem, though. One couldn’t get too far away from the heart of the palace without ending up in the grounds of Westminster’s other great building, its Benedictine abbey.

The Jewel Tower and its moat were eventually built so close to the abbey that they actually encroached on its land. The monks, bitterly resenting this violation, naturally protested, not only at the loss of their land, but also because the new building blocked a route which they had formerly used to reach their watermill, as well as for feast-day processions around the abbey precinct.

DIVINE INTERVENTION

Their anger was later recorded in the 15th-century ‘Black Book’ of Westminster Abbey, and there is no doubt, based on that account, whom they regarded as the villain of the piece: one William Usshborne, Keeper of the King’s Privy Palace and, apparently, instigator of the seizure of their land.

The Black Book relates how the builders of the Jewel Tower disturbed the remains of a hermitage and the lead coffin of the hermit within it:

Master William Usshborne, with the agreement of a leadworker of the church of Westminster, hatched a plan to lift the lead coffin out of the ground using its iron rings, and to throw the hermit’s bones into a pit in the monks’ cemetery. But as soon as the said leadworker carried the lead coffin into his workshop, he suddenly fell down, and all strength departed from his body, and he could no longer carry on living. After a brief time, he died and passed on from this world.

DIVINE INTERVENTION, PART II

Usshborne, it would seem, didn’t get the message. The Black Book goes on to relate, with some relish, the fate that eventually overtook him, too:

In the time of King Edward III, a certain keeper of the lord king’s palace named William Usshborne unjustly seized for the king’s use a certain close belonging to the prior of Westminster, and here he made a garden with a pond in which to keep live fish [perhaps the Jewel Tower moat?].

It so happened that one day around the feast of Saint Peter ad Vincula, he invited some of his Westminster neighbours to dinner, and he prepared his table with a large pike, caught in this fishpond. As they all sat down to dinner, this William quickly took some of the pike, but as soon as he had swallowed two or three mouthfuls of the fish, he began shouting almost dementedly in these words – ‘it is trying to choke me!’ After crying out in pain many times in this way, suddenly he fell to the ground and died a wretched death without the last rites. He was then carried into the parish church of Saint Margaret and buried in the choir, because of the dignity of his office.

It was said that this came to pass because he had confiscated the meadow and garden of the infirmary and the prior of Westminster’s garden for the use of King Edward III. For this, there was absolutely no compensation to the church of Westminster.

This account was written long after the abbot and monks had relinquished their claim to the Jewel Tower site, but the author’s delight at the justice of Usshborne’s fate suggests it wasn’t a dispute that was quickly forgotten.

By Jeremy Ashbee

Medieval stories

-

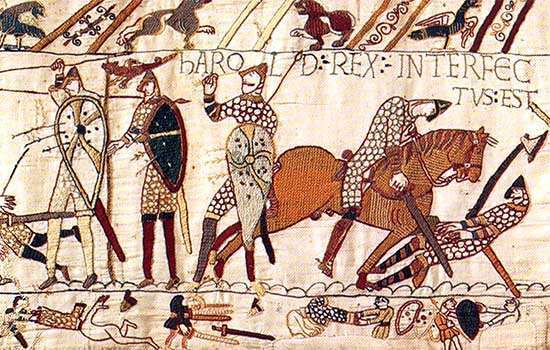

What Happened at the Battle of Hastings?

In the early morning of 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Find out what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

Piers Gaveston and the Downfall of Edward II

Discover how Edward II’s reliance on his ‘favourites’ and possible lovers led to his abdication and death.

-

The Massacre of the Jews at Clifford's Tower

One of the worst anti-Semitic massacres of the Middle Ages took place in York in 1190. The city’s entire Jewish community was trapped by an angry mob inside the tower of York Castle.

-

Lord Hastings, Richard III and an Unfinished Castle

How William Lord Hastings’s ultra-fashionable castle at Kirby Muxloe, Leicestershire, was left incomplete following his summary and shocking execution by the future Richard III.

-

Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Why did Richard, Earl of Cornwall and one of the richest men in Europe, swap three castles for a rock?

-

Where Did the Battle of Hastings Happen?

Historians have long accepted that Battle Abbey was built ‘on the very spot’ where William the Conqueror defeated King Harold. Is there any truth in claims that the battle took place elsewhere?

-

The Misbehaving Monks of Hailes Abbey

Visitation records from abbots who came to inspect Hailes Abbey offer tantalising glimpses into the lives of the monks who lived there and the vices that may have tempted them.

-

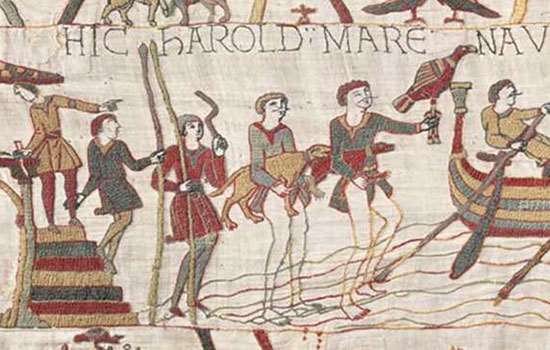

A Canterbury Tale: The Bayeux Tapestry and St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine’s Abbey has long been celebrated for its contribution to English Christianity. But could it also be the birthplace of one of the most famous artefacts in history?

More about medieval England

-

Medieval: Architecture

For more than a century after the Battle of Hastings, all substantial stone buildings in England were built in the Romanesque style, known in the British Isles as Norman. It was superseded from the later 12th century by a new style – the Gothic.

-

Medieval: Religion

The Church was a pervasive force in people’s lives, with the power and influence of the Catholic Church – then the only Church in western Europe – reaching its zenith in England in the Middle Ages.

-

Medieval: Warfare

The Norman Conquest was achieved largely thanks to two instruments of war previously unknown in England: the mounted, armoured knight, and the castle.