Research on the Jewel Tower

The Jewel Tower has been relatively little studied by modern scholars, mainly because until recent years it has been inaccessible and largely hidden by other buildings. In the early years of the 21st century, however, a number of studies of both medieval and Tudor royal treasuries have been produced, stimulating consideration of this important element of royal life, and the place in it of repositories such as the Jewel Tower.

The Tower’s Architecture

The relative simplicity of the tower’s architecture has not commended it to architectural historians studying either the Middle Ages or the 18th century. Unusually, until very recently it was the original guidebook – by Arnold J Taylor, and first published in 1956 – that provided the most detailed account in print.[1] Only recently has research shed further light on the building.

Layout of the Privy Palace

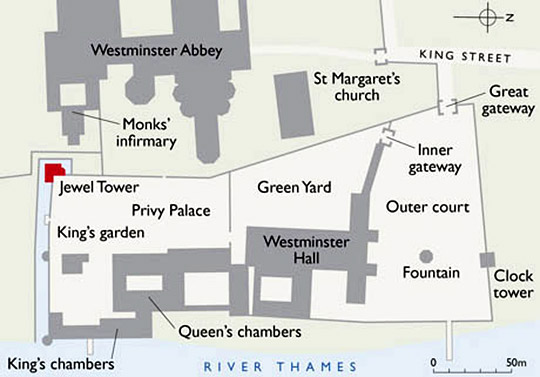

The layout of the Privy Palace is comparatively little known, as a consequence of the destruction of several buildings in the 16th century. Others survived within the Parliamentary estate until the 19th century, and were recorded before and after the 1834 fire, following which demolition was almost total.

Moreover the nature of medieval and Tudor use precluded the pictorial recording of the buildings by artists, who would generally have been excluded from this area.[2]

For these reasons, references to the buildings in administrative documents are of particular value: for example, 15th-century accounts describe new buildings in the vicinity of the Jewel Tower.[3]

Professor Christopher Wilson has previously summarised the layout of the principal buildings as a comparison with Edward III’s new complex at Windsor Castle.[4] At a conference in the summer of 2013, a more detailed treatment of this question is anticipated from him. Other papers in the same conference are expected to clarify the development of Old Palace Yard between the 16th and 19th centuries.[5]

The Royal Treasury

The documentation associated with the Jewel Tower allows a much better understanding of its operations than does the fabric itself. This is particularly true of the earliest decades of the tower’s existence, when detailed descriptions of the contents can be found in writs and indentures connected with keepers of the king's jewels.

A great deal of documentation for the royal treasuries is frustratingly unspecific about locations,[6] but on present evidence the Jewel Tower appears to have been a place of minor importance compared with the Tower of London (principally the White Tower) and the Pyx Chamber in the cloister of Westminster Abbey.

The recent detailed study by Jenny Stratford of the royal treasury of Richard II has provided invaluable insights into the king's treasure at this period and in the reign of Edward III.[7] This study makes some reference to the immediate aftermath, but there is a need for a corresponding research programme into 15th-century details of the items kept in the Jewel Tower and the regimes of various keepers of the king’s gold and silver vessels.

Parliamentary Record Office

Recent work by historians of Parliament has shown that the Jewel Tower was being used for the storage of Parliamentary records by 1600 and almost certainly much earlier.[8] This throws into question the use of the tower between 1550 and 1600: previous suggestions that it was rented out to courtiers would repay further study.[9]

Board of Trade Standards Department

The operation of the Board of Trade Standards Department in and around the Jewel Tower is documented in a number of files held in the National Archives, but has not been the subject of detailed study in its own right.[10]

READ MORE ABOUT THE JEWEL TOWER

Footnotes

1. AJ Taylor, The Jewel Tower (Ministry of Works guidebook, London, 1956; revised edn, London, 1996).

2. One of the few depictions of value is Victoria and Albert Museum drawing E128-1924, approximately dated to the 1520s or 1530s (accessed 20 May 2013). This shows the river frontage of the palace in some detail: the Jewel Tower itself almost certainly appears in the background.

3. Eg TNA E364/89 rot E; E364/100 rot B.

4. C Wilson, ‘The royal lodgings of Edward III at Windsor Castle: form, function, representation’, in Windsor: Medieval Archaeology, Art and Architecture of the Thames Valley, ed L Keen and E Scarff (Leeds, 2002), 15–93.

5. British Archaeological Association Summer Conference, July 2013. Papers from the conference should be published in the Transactions series, for which the Westminster volume should be expected by 2015.

6. Numerous documents describing royal treasuries are held within the generic document class TNA E101 (Exchequer, King's Remembrancer, Various Accounts) and can be identified in the National Archives online catalogue using search terms including ‘jewel’ and ‘treasure’. These documents are extremely evocative and provide much detail about the contents of royal treasuries, but caution should be exercised in asserting a direct linkage to the Jewel Tower.

7. J Stratford, Richard II and the English Royal Treasure (Woodbridge, 2012). The website Richard II's Treasure is a useful resource based on the treasure roll or inventory of 1398 or 1399.

8. A Thrush, ‘The House of Lords’ records repository and the Clerk of the Parliaments' house: a Tudor achievement’, Parliamentary History, 21:3 (2002), 367–73 (subscription required; accessed 20 May 2013).

9. AJ Taylor, The Jewel Tower (guidebook, revised edn, London, 1996), 11.

10. TNA BT 101/78, 101/188, 101/878 and 101/953.