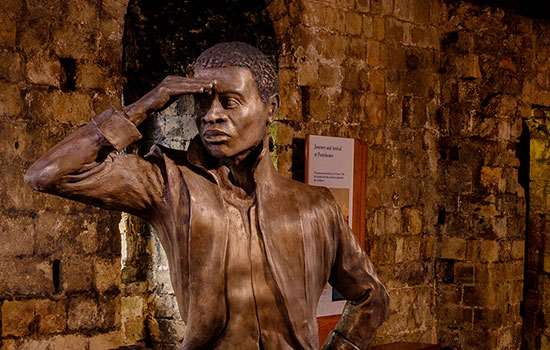

James Somerset

James Somerset was born around 1741 in West Africa and was about eight years old when he was captured and sold to European slavers. On 1 August 1749 he was sold in Norfolk, Virginia, to the Scottish merchant Charles Steuart (or Stewart). Nothing is known about James Somerset’s childhood in Africa, and scholars have not been to identify the ship on which he was transported to North America. One possibility is the sloop Diamond, which regularly transported enslaved people for sale through Steuart’s firm and made frequent voyages at the time, while two other ships, the William and the Susanna, arrived in Virginia between 31 March and 1 August 1749.[1]

Most of the evidence for Somerset’s life comes from rare mentions in Steuart’s correspondence.[2] In these letters and in the Virginia tithable records for Norfolk County, Somerset is referred to only as ‘Somerset’. This name was most likely given to him by slave traders when he was transported to America or in Jamaica, where he may first have disembarked. Between 1756 and 1763, Steuart owned at least six enslaved people.[3]

In 1764, Steuart became Receiver-General of Customs in Boston and took Somerset there. Five years later Steuart relocated to England, and took Somerset with him, selling or leasing his other enslaved people. While in London, they lived in Baldwin’s Gardens in Holborn.

Throughout his enslavement, Somerset was sent on errands by Steuart which took him not only around London but also into the English countryside. This is most likely how Somerset came into contact with other black people as well as white abolitionists. In 1764 the Gentleman’s Magazine estimated there were up to 20,000 black people in London alone. During the Somerset case, Lord Mansfield gave an estimate of 15,000.

Black communities in England

England’s black communities lived predominantly in London at this time, but there were also black people living in other parts of England, mostly in Bristol and Liverpool, as well as in the wider countryside. Black people in England in the 18th century originated from many countries and backgrounds, for whom the black communities in London provided both social links and an informal political network.

It was probably through these communities that Somerset came into contact with Thomas Walkin, Elizabeth Cade and John Marlow, who became his godparents when he was baptised in August 1771 in the church of St Andrew, Holborn. It is possible that the motivation for Somerset’s baptism was the belief, widely held in England at the time, that enslaved people who became Christians simultaneously became free.

The tapestry of legal rulings and opinions on both sides of the Atlantic on the status of enslaved people in England, and whether baptism conferred freedom, had resulted in legal ambiguity. This confusion left many people under the false impression that baptism was an effective mechanism to free enslaved people in England. Church records from the 17th century contain references to black people, and by the 18th century baptisms of black servants and enslaved people appear more frequently in such records.[4] It is possible that this belief contributed to the motivation for Somerset’s baptism in 1771.

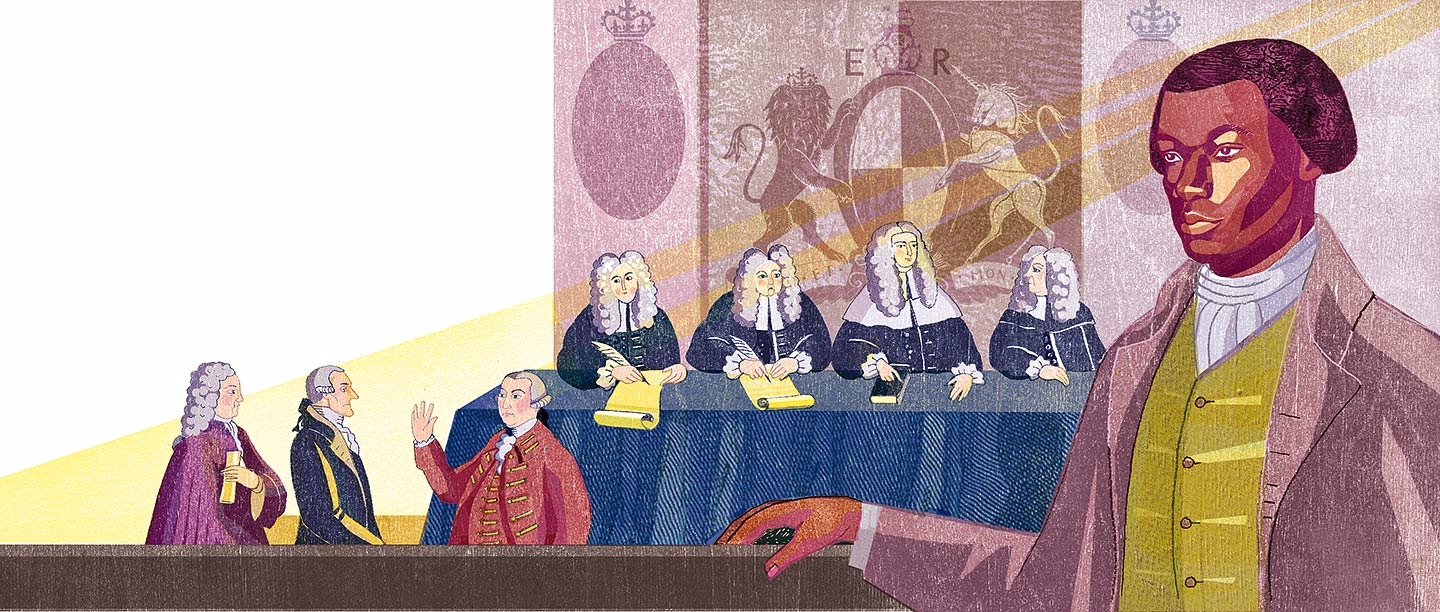

THE CASE OF SOMERSET V STEUART

On 1 October 1771 Somerset left Steuart and refused to return to a state of servitude. On 26 November, on Steuart’s orders, he was kidnapped by slave hunters and delivered to Captain John Knowles, captain of the ship Ann and Mary. He was gaoled on board awaiting transportation to Jamaica, where Steuart directed that he should be sold to a plantation for labour.

On 3 December, however, Somerset’s godparents applied before the Court of King's Bench for a writ of habeas corpus (using Somerset’s Christian name, James, which was probably added – and perhaps chosen by him – at his baptism). Literally translated, ‘habeas corpus’ means ‘you may have the body’ and was the expression used in the Middle Ages to bring a prisoner into court. Its purpose since the 17th century was to protect against false imprisonment, as habeas corpus determines whether a prisoner has been afforded due process, not whether he or she is guilty. As such, Somerset’s case was argued against Captain Knowles, the person accused of unlawfully detaining Somerset.

Six days later, Knowles produced Somerset before the Court of King’s Bench, which had to determine whether his imprisonment was lawful. The Chief Justice presiding over the case was Kenwood’s Lord Mansfield. A hearing was ordered for 21 January, and in the meantime he set Somerset free on recognisance. Meanwhile Somerset enlisted Granville Sharp, an inveterate opponent of the institution of slavery, to support his cause.

Who was Lord Mansfield?

At the time of the case, William Murray, Baron (later 1st Earl) of Mansfield, was living at Kenwood House, on the edge of Hampstead Heath, with his wife and two great-nieces, Lady Elizabeth Murray and Dido Belle. Dido, born in 1761, was the mixed-heritage daughter of an enslaved African woman known as Maria Bell and Mansfield’s nephew, Captain John Lindsay, who brought Dido to England and placed her in the care of his uncle in or before 1766.

As Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench between 1756 and 1788, Mansfield was the most powerful judge in Britain, overseeing significant reforms to the legal system such as improving access to justice and modernising commercial, merchant and common law.

The opposing sides

Mansfield tried various ways to avoid hearing the case. Initially, he tried to persuade Steuart to free Somerset, as had happened on similar occasions, but Steuart refused. The West Indian planters who financed the defence also refused all offers to settle out of court. As a last resort Mansfield tried to persuade Somerset’s godmother to buy him, but she refused on principle. Resigned to the case proceeding and aware of its potential impact, Mansfield declared, ‘if the parties will have judgment, fiat Justitia ruat coelum [let justice be done though the heavens fall]’.

Somerset’s case was immediately seen as a test of the legality of slavery in England, and abolitionists and those with investments in West Indian plantations followed it closely. While the planters pressed for a decision recognising and enforcing in England colonial laws relating to slavery, abolitionists like Sharp advocated for the opposite result.

Somerset’s case was pleaded by William Davy, John Glynne, Francis Hargrave, James Mansfield and John Alleyne, and financed by Sharp. Sharp saw the case as an opportunity to promote the arguments he had made in A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery in England (1769). However, he was concerned that his presence in the legal team might adversely affect the trial’s outcome, so he conferred closely with Hargrave, a young lawyer on the case, and otherwise kept a low profile.

The opposing position was argued by John Dunning and William Wallace, whose services were funded by West Indian planters. Shortly before the ruling, Charles Steuart wrote: ‘the West Indian Planters and Merchants have taken it off my hands, and I shall be entirely directed by them in the further defense of it.’

The trial

When Somerset’s case finally came to trial, Dunning and Wallace argued that slavery was the 18th-century successor of ‘villeinage’ and therefore part of a continuous legal practice. Villeinage was a medieval feudal concept that created a bond–service contract between a lord who owned land and a feudal villein who held or occupied it, and could be required to provide services to the lord without payment.

Somerset’s lawyers defined villeinage as ‘a slavery in blood and family, one uninterruptedly transmitted through a long line of ancestors’, and argued that English ancestry was a requirement of villeinage. They argued that villeinage had anyway expired, that there was no positive law relating to slavery in England, and that the law of Virginia, under which the contract for Somerset’s enslavement was made, did not apply in England. Further, Somerset could not be accused of breach of contract because the basic requirement for any contract – that the parties be free to enter into it – had not been met.

The ruling

Despite the complex legal arguments, Mansfield was determined to issue a narrow ruling, clarifying that ‘The only question before us is, whether the cause on the return is sufficient? If it is, the negro must be discharged.’ The question at stake was not the legality of slavery, but whether Knowles – on behalf of Steuart – had a legal right to detain Somerset, the legal protection which habeas corpus affords.

On 22 June 1772, Mansfield decided:

Accordingly, the return states, that the slave departed and refused to serve; whereupon he was kept, to be sold abroad. So high an act of dominion must be recognized by the law of the country where it is used. … The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons … but only by positive law. … It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from this decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.

The court held that ‘a master could not seize a slave in England and detain him preparatory to sending him out of the realm to be sold’. It also ruled that habeas corpus was a constitutional right available to slaves to forestall such seizure, deportation and sale, because they were not chattel, or mere property – they were servants and thus persons invested with certain (but limited) constitutional protections.

Mansfield took great care to avoid offering a ruling on the legal status of enslaved people and their rights in England. However, it was perceived – and reported – quite differently on both sides of the Atlantic. Many, including James Somerset himself, understood the decision to have effectively abolished slavery in England.

Legacy

Somerset v Stewart attracted much popular attention, including from London’s black community who sent representatives to follow the hearings and whose celebrations were noted in reports of the judgment. On 27 June 1772, the Public Advertiser reported that

near 200 Blacks … had an Entertainment at a Public-house in Westminster, to celebrate the Triumph which their Brother Somerset had obtained over Mr. Stuart his Master. Lord Mansfield’s Health was echoed round the Room; and the evening was concluded with a Ball.

Somerset himself appears to have adopted the broader interpretation of the ruling and wrote to at least one enslaved person, encouraging him to desert his master. In a letter dated 10 July 1772, a friend of Charles Steuart wrote to him:

I am disappointed by Mr. Dublin, who has run away. He told the Servants that he had recd. a letter from his Unkle Sommerset acquainting him that Lord Mansfield had given them their freedoms, & he was determined to leave me … I don’t find that he is gone of [sic] with any thing of mine … I believe I shall not give my Self any trouble to look after the ungrateful Villain.

Whether Somerset was Dublin’s relation or acquaintance, this letter offers a glimpse into the black communities of Britain in this period, and suggests not only a process by which knowledge of Mansfield’s ruling became known outside London, but also the way in which it was understood and acted upon.

This letter, dated 18 days after the ruling in Somerset v Stewart was issued, is the last evidence we have of James Somerset.

‘I AM JAMES SOMERSET’

Akyaaba Addai-Sebo (1950–) is a Ghanaian analyst, journalist and pan-African activist credited with developing the recognition of October as Black History Month in 1987 in the UK. His poem ‘I AM JAMES SOMERSET’ was read on 22 June 2022 at the Somerset v Stewart 250th Anniversary event at Kenwood House. The poem has been gifted to the English Heritage collection.

Download the poemFurther reading

Bouchard, D, ‘Fight for freedom’. English Heritage Members’ Magazine (May 2022), 44–47

Gerzina, G, Black England: A Forgotten Georgian History (London, 2022)

Walvin, J, Black and White: The Negro in English Society, 1555–1945 (London, 1973)

Weiner, MS, ‘Notes and Documents - New Biographical Evidence on Somerset’s Case’. Slavery & Abolition, 23 (2002), 121–36

Wise, SM, Though the Heavens May Fall: The landmark trial that led to the end of human slavery (Cambridge, USA, 2005)

Related content

-

Black history

Black history is a key part of England’s story, reaching back many centuries, and helps us to reflect on the connections between past and present.

-

Black Lives in 18th-Century Britain

We take a look at the lives of black people – including soldiers, servants and independent citizens – who lived under the shadow of slavery in 18th-century Britain.

-

Dido Belle

Learn more about the life of Dido Belle, a mixed-race woman raised at Kenwood at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.