John, Lord Lovell

John Lovell, 5th Baron Lovell (c.1342–1408), was an experienced soldier, fighting in France in the 1360s and as a mercenary-knight in Prussia in the 1370s. His military experience, political skills and his marriage to Maud Holland, a relative of Richard II, brought him increased prestige and wealth. He became the governor of the royal castle of Devizes in 1381 – the king’s man in Wiltshire.

But Lovell wanted his own castle as a symbol of his new-found status and wealth. He had been granted land in Wiltshire by the king and he added to his new base by buying the manor of Wardour in 1386 for £1,000. Here in the 1390s he built a splendid new castle, probably designed by William Wynford, a celebrated mason-architect who had worked at Windsor Castle.

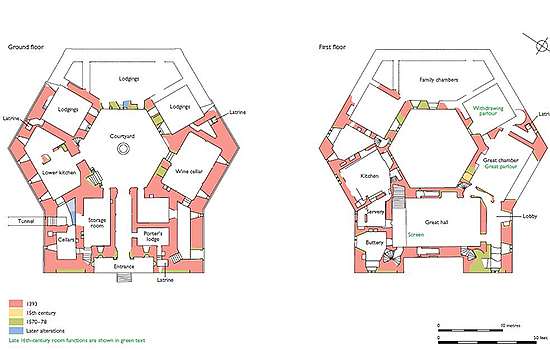

Perhaps inspired by Queenborough Castle in Kent, Wynford’s design for Lovell was a show castle of remarkable symmetry. The castle is a hexagon with a rectangle added to one side (the twin-towered entrance), with a walled outer precinct echoing the geometrical shape.

The medieval castle

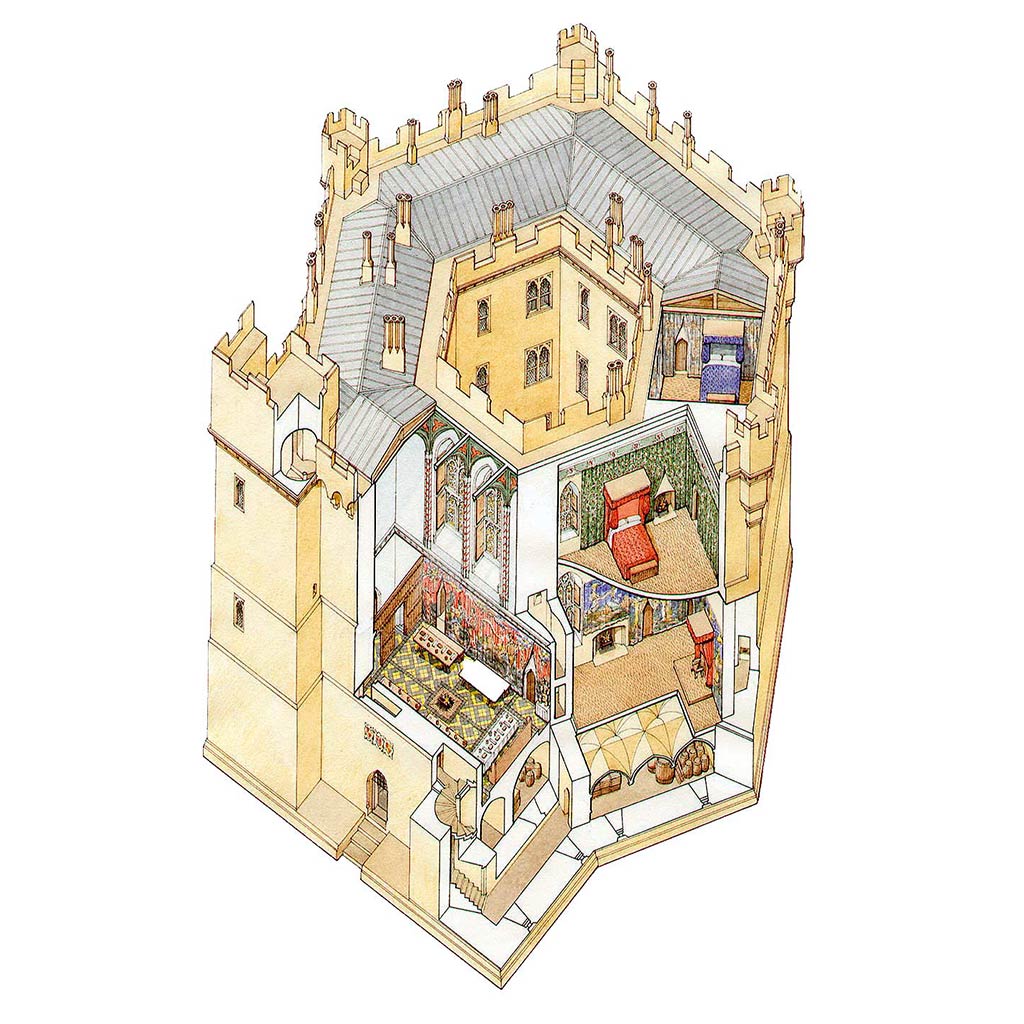

Lord Lovell’s castle had five storeys, arranged around a small hexagonal courtyard.

On the ground floor were cellars and accommodation for the junior servants. Above, on the first floor, lay the kitchen and the important function rooms – the hall and great chamber – and, most likely, the chapel. The hall was the heart of the castle, the space in which Lovell would receive and impress guests, and where the whole household would dine. The great chamber was a smaller and more intimate version of the hall, reserved for the family and important guests.

These first-floor rooms were at least two storeys high, with the hall rising all the way to the roof of the castle and lit by dramatic tall windows.

The second floor had a few small chambers (between the double-height rooms of the floor below) and the third and fourth floors housed the main lodging chambers for Lovell and his guests. These chambers were fine rooms, with good views and luxurious facilities including individual fireplaces and latrines.

An Elizabethan mansion

The Lovells forfeited the castle in 1461 as its then owner, the 8th Lord Lovell, supported the Lancastrian Henry VI, who was deposed that year. After a period of changing ownership it was eventually sold in 1547 to Sir Thomas Arundell. However, Sir Thomas was executed five years later, a victim of the coup that overthrew Protector Somerset, who had ruled England during the minority of the young Edward VI.

His son Sir Matthew Arundell (1535–98) rose through the ranks of Elizabeth I’s government and bought Old Wardour back for the family in 1570. He almost certainly employed the talented Elizabethan architect Robert Smythson (who designed Longleat in Wiltshire) to work on the castle.

Smythson and Arundell did not, however, want a new Elizabethan house like Longleat. They recognised the innovative medieval symmetry of Old Wardour and simply modernised it. Smythson added a new front door with classical pilasters and elegant alcove seats on each side. Above the new door Sir Matthew placed his coat of arms and an inscription marking the restoration of the family and their seat, and exonerating his executed father.

Above these additions was a gilded bust of Jesus, a rather daring ornament in the Protestant reign of Elizabeth, when religious imagery was inherently suspicious. Although Sir Matthew was outwardly Protestant, he was almost certainly a secret Catholic like his father, brother and son.

Use the interactive image below to view these features.

A horse enthusiast

Matthew Arundell was a horse enthusiast. In his will of 1598 he pays particular attention to his horses, bequeathing one each to 20 friends and servants. These included fine animals such as a gelding (to be given to his executor Lord William Howard) and a horse called Otoman (to the leading statesman Sir Robert Cecil), as well as his ‘white spavined [decrepit] mare’ (bequeathed to George his cook). And his son, Thomas Arundell, was to have the ‘residue of my mares, horses, colts and geldings’.

The ruined stables at Old Wardour (now part of the private Old Wardour House, to the south of the castle) date to the 17th century, but there must also have been impressive earlier stables to house Sir Matthew’s collection.

Civil War battleground

When a long struggle for power between king and Parliament culminated in the outbreak of civil war in 1642, many English men and women had to choose which side to support. Catholic families like the Arundells of Wardour were solidly on the side of Charles I. And so Thomas, 2nd Lord Arundell (c.1586–1643), joined the king in Oxford in spring 1643, leaving his wife, Lady Blanche Arundell (1583/4–1649), in charge of the castle.

On 2 May, the local Parliamentary commander Sir Edward Hungerford arrived at Wardour Castle intending to occupy it. But Blanche refused to surrender. For six days she and her small force of about 25 men resisted the siege, only surrendering after Hungerford threatened to blow up the castle. Her heroism was widely reported in Royalist broadside news-sheets, along with that of the maidservants who reloaded the defenders’ guns.

Soon afterwards, on 19 May, Lady Blanche’s husband was killed in battle near Oxford. In December their son Henry, 3rd Lord Arundell (1608–94), arrived at Wardour, intending to retake the castle from the Parliamentarian garrison, led by Edmund Ludlow. A three-month siege ensued, which finally ended in March 1644 when Henry Arundell blew up one side of his own castle with a mine and Ludlow surrendered.

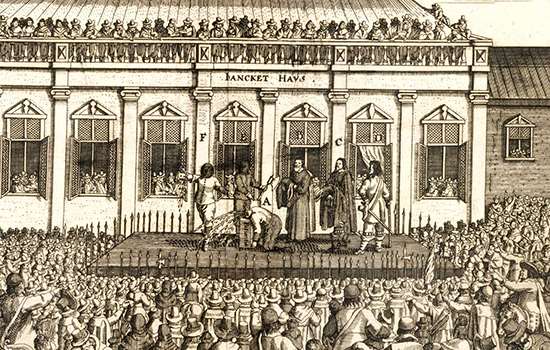

The ruined castle was later confiscated, after the final victory of the Parliamentarians in 1648 and the execution of Charles I in 1649. Henry eventually recovered his estates in 1660 when the monarchy was restored. Instead of rebuilding the castle, however, he built a smaller house, now known as Old Wardour House, just to the south (now in private ownership).

Read more about the siegesA picturesque ruin

In 1763 Henry, 8th Lord Arundell (1740–1808), married the wealthy heiress Mary Conquest and they decided to build a new home. New Wardour Castle, a classical building designed by James Paine (and now privately owned), lies a few hundred metres west of Old Wardour. But the Arundells did not simply abandon Old Wardour. In 1764 they commissioned a landscaped park design for the new house, featuring woods, a lake and a picturesque ruin – the old castle.

Landscape architects such as Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown had made this style of English garden fashionable. Instead of straight avenues and walled gardens, the new style improved nature with lakes, winding roads, clumps of carefully sited trees and viewpoints. Capability Brown had been engaged by the previous Lord Arundell to design a landscape at Wardour, but the works carried out were in fact by a less famous designer, Richard Woods.

The Arundells gradually added other features to their picturesque landscape, including a banqueting house probably designed by James Paine (in 1773), a grotto of stone seats (in about 1770), and a larger stone grotto by the local designers Josiah and Joseph Lane (in 1792). All these features played with the Gothic theme of the ruined castle – the banqueting house with its battlements and ogee-arched doors, the grottoes with their reused medieval (and prehistoric) stones.

19TH- AND 20TH-CENTURY WARDOUR

In the 19th century the romantic creeper-clad ruins of the old castle were opened to the public, and became a popular tourist attraction. By 1836 the banqueting house had been set up to provide refreshments.

Gerald, 15th Lord Arundell, gave the old castle into the guardianship of the state in 1936. His son John, 16th and last Lord Arundell, was released early (but ill and dying from tuberculosis) from a German prisoner-of-war camp in 1944. He died days after reaching Britain.

The Arundell family still own the site and much of the surrounding parkland, and the castle ruins are maintained by English Heritage.

Further reading

M Girouard, Old Wardour Castle (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2012)

Historic England, listed building description (accessed 16 Sept 2020)

Historic England, listed park and garden description (accessed 16 Sept 2020)

Historic England, scheduled monument description (accessed 16 Sept 2020)

Historic England, descriptions for the grotto, [New] Wardour Castle, banqueting house and other park features (accessed 16 Sept 2020)

A Plowden, Women All on Fire: The Women of the English Civil War (Stroud, 1988) [includes an account of the two Civil War sieges of Wardour]

Find out more

-

Visit Old Wardour

Showpiece house to romantic ruin

-

Blanche Arundell, Defender of Wardour Castle

Read about how Lady Blanche Arundell heroically led a small band of men and women in defence of her home, Old Wardour Castle, when it came under siege during the English Civil War.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from sieges to the Isle of Wight castle where Charles I was imprisoned.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of Old Wardour to discover how the castle’s buildings have changed over time.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook gives a full tour and history of the site, and is richly illustrated with historical images, maps, plans and photographs.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.