‘White daisies, red poppies…’

The devastation of the First World War changed not only the lives of those caught up in the war but also the landscape where the battles were fought. The countryside was churned up by tanks, trenches and bombs. Woods, meadows and farmland were changed beyond recognition.

Those who saw the battlefields after the fighting had ended marvelled at their speed of regeneration. Soon after the fighting stopped, natural growth started to reclaim these battlefields.

The war artist William Orpen and poet John Masefield were both overcome by the floral spectacle that arose shortly after fighting ceased. Orpen commented ‘White daisies, red poppies, and a blue flower, great masses of them, stretched for miles and miles’. Masefield mentioned ‘one summer with its flowers will cover most of the ruin that man can make’.

Ernest Owen Johnson, 1875-1917

Employed as a garden labourer at Osborne at the outbreak of the First World War, Ernest Johnson was drafted into the Royal Naval Division (Royal Naval reservists who could not be found a ship to serve on) on 17 August 1916.

After an illness which took Ernest away from his battalion, he returned to the front on 10th November 1917 at the end of the Second Battle of Passchendaele. The Battle of Cambrai started on 20 November 1917 and at 6.30am on 30 December Ernest’s division was heavily bombed for 15 minutes.

Ernest died that day, less than a year and half after he was drafted. His remains are buried at Flesquières Hill British Cemetery, Cambrai, France, in grave V.C.13.

English Heritage remembers

In 2018, to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War, English Heritage gardeners, volunteers and local schoolchildren worked together to remember those lost.

At Osborne, a flower bed was created for the summer. It was sown with plants that were recorded growing in the Somme area of northern France during 1916–17, and illustrated how nature reclaims the sites of warfare.

The flower bed bloomed with wildflowers to waist height. Poppies and cornflowers blossomed among barbed wire, and small white crosses were visible through the plants. The bed was dedicated to the garden staff of the Royal Parks (Osborne was a Royal Park at the time of the war) who lost their lives at war.

A place of recovery

Osborne has further good reasons to mark the First World War. The house itself was a convalescent home for casualties for many years after 1904. In the First World War officers were not allowed home to convalesce as it delayed their return to the Front; many were sent to Osborne.

Those recovering there included AA Milne, of Winnie the Pooh fame, and novelist Robert Graves. They would have walked in the walled garden to aid their recovery.

Very few families on the Isle would not have been impacted by the war. The Isle of Wight County Press estimated at least 1,650 islanders died, based on casualty reports in The Times. It is this number whose names appear on the County War memorial at nearby Carisbrooke Castle.

More First World War history at our sites

-

A soldier's letters

How John Glasson Thomas's letters to Gertie Brooks offer a very special record of one man's Great War.

-

The Shelling of Scarborough in 1914

Read about the devastating attack on Scarborough by German warships in 1914 – the first targeting of civilians on English soil during the First World War.

-

The Richmond Sixteen

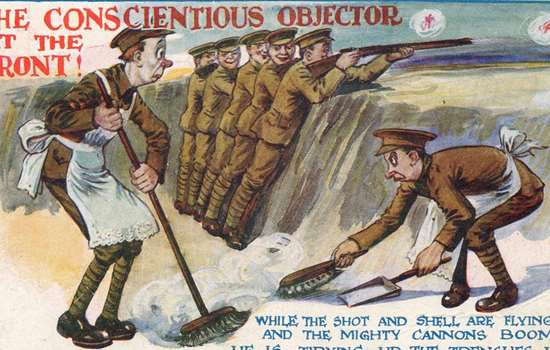

How 16 First World War conscientious objectors detained at Richmond Castle were taken to France and sentenced to death for refusing to obey orders.

-

Attitudes to Conscientious Objection and Conscription

Find out how conscription came about during the First World War, and what happened to the men who applied for exemption.