The Roman Fort

We know little about the early history of Anderida, the Roman fort at Pevensey. Tree-ring dating of wooden piles sunk into the wall foundations suggests that it was built in about AD 290.[1]

At that time the coastal defences of Roman Britain seem to have been systematically strengthened, and a number of other forts around the south and east coasts, such as Portchester, Burgh, Richborough and Lympne, were built or reconstructed. These share many architectural features with Pevensey, particularly the D-shaped wall towers which were a new feature of Roman fortifications at this time.

One explanation for this sudden burst of building activity is the usurpation of Roman rule in Britain between AD 286 and 296 by the military commander Carausius and his successor, Allectus. Both were self-proclaimed emperors of Britain and parts of Gaul (France), and had a strong motive to fortify the coast against reconquest by the central Roman government. Coins of this period have been found in the wall foundations.[2] However, when the Emperor Constantius invaded Britain in 296 there is no indication that the coastal forts, including Pevensey, played a part.

Anderida is first documented a late Roman document, the Notitia Dignitatum, which lists all civil and military posts in the Roman empire.[3] It was one of nine forts around the south and east coasts commanded by the Comes Litoris Saxonici per Britanniam, or the ‘Count of the Saxon Shore’. Whether or not these forts were established as a coherent defensive system is not clear, but some may have had naval detachments, working also with ships based at coastal forts in northern France. The Notitia mentions a fleet, the classis Anderidaensis, which took its name from Anderida. The date and circumstances of compilation of the western empire section of the Notitia are uncertain but it usually regarded as late 4th or early 5th century, though some out-of-date information may have been included.

After the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain in the early 5th century, Anderida’s walls continued to shelter a community. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 471 the fort was besieged and its population slaughtered by Saxon raiders.[4]

The fort was abandoned for around a century before it was inhabited again. Little is known about it in Anglo-Saxon period, though traces found by archaeologists such as fragments of glass suggest it was a high-status place. It may even have acted as a royal centre.

Read more about the Saxon Shore fortsThe Norman Landing

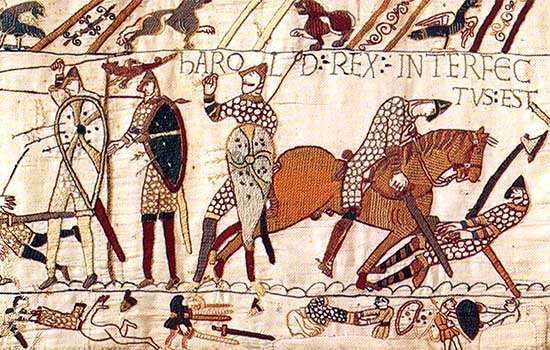

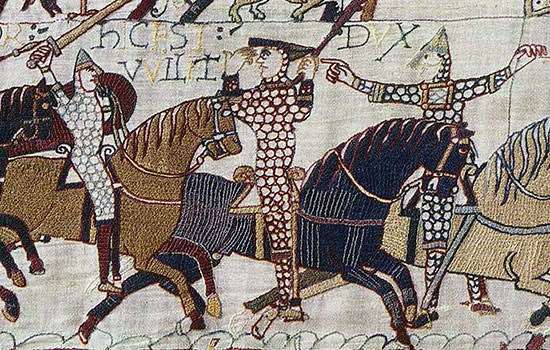

Pevensey’s history changed dramatically when, before dawn on 28 September 1066 – three days after King Harold’s victory at Stamford Bridge – William, Duke of Normandy, sailed his invading fleet of about 700 ships into the Bay of Pevensey. After landing, he immediately built a temporary fortification, almost certainly within the walls of the Roman fort, to shelter his troops.[5] He cut a ditch across the peninsula to isolate the ruins from the mainland and repaired the walls to create a castle.

The next day William marched his army away along the coast to Hastings, and waited for Harold to arrive from the north – in the meantime pillaging and burning the surrounding countryside. His subsequent victory over King Harold at the Battle of Hastings and coronation as King of England heralded a new era in English history.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE NORMAN CONQUESTThe Norman Castle

When William left England in 1067 to make a triumphal tour of Normandy, he chose to sail from Pevensey. He seems to have made a show while at Pevensey of distributing lands to his victorious followers, before a collected body of defeated Anglo-Saxon nobles. It was probably on this occasion that he gave the castle with its hinterland, known as the ‘Rape’ of Pevensey, to his half-brother Robert, Count of Mortain (d.1095).

Pevensey offered a natural anchorage facing the Normandy coast, and any castle with command of this was of obvious strategic importance. Control of it not only ensured lines of communication with the Continent, but prevented it from being used as the base for another seaborne invasion. It was probably Robert who created the first permanent defences, refortifying the Roman perimeter wall and creating two enclosures (or baileys) within it, divided by a ditch and a timber palisade.

In 1088, the year after William’s death, Pevensey’s strategic importance was demonstrated again during the war between his eldest son, Robert Curthose, who succeeded William as Duke of Normandy, and Robert's younger brother William Rufus, who succeeded to the English throne. When an attempt was made to make Robert king of England in William's place, the Count of Mortain and his brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, supported Duke Robert and held Pevensey Castle against the king.

There was a real danger that Robert would invade England in the footsteps of his father. To prevent this, William Rufus personally led a siege of Pevensey by land and sea. The castle’s powerful defences resisted every assault, but after six weeks food was running short, and with no prospect of reinforcements from Robert the rebels agreed a truce.

Despite this rebellion the Count of Mortain was allowed to keep Pevensey. But his son subsequently lost it, along with the other family estates in England, as a result of his opposition to William Rufus’s successor and younger brother, Henry I (r.1100–35). Henry granted most of this confiscated property to a Norman lord, Gilbert Laigle.

Nevertheless, the castle seems to have been retained in royal hands for security. In 1101, when Duke Robert again threatened to invade England, Henry I spent the summer at Pevensey in anticipation of an attack.

Buy The Guidebook to Pevensey Castle

The Development of the Castle

During King Stephen’s reign (1135–54) the Laigle family lost possession of Pevensey, and the castle was granted to Gilbert de Clare, 1st Earl of Pembroke. When Gilbert rebelled in 1147 Stephen blockaded the castle until its inhabitants were starved into submission.[6] The Crown then directly repossessed it.

Royal records of repairs made to palisades in the 1180s suggest that at this date, aside from the Roman walls, Pevensey’s defences were still largely of earth and timber.[7] The first major stone buildings may date from the 1190s, when regular and substantial payments were made towards unspecified works by Richard I (r.1189–99).[8] He may have built the keep and the gatehouse, although the ruins of the former could belong to a ‘Tower of Pevensey’ described in 1129–30.[9]

The castle Richard developed may have been deliberately destroyed during the turbulent reign of his successor, John (r.1199–1216). By 1216 he was desperately fighting off an invasion led by the French king’s son, Prince Louis, and as he retreated through Sussex he gave orders to destroy the castles of Pevensey and Hastings (an act known as ‘slighting’). Though the castle played no part in Louis’ invasion, it is uncertain whether John’s orders were ever followed.

Baronial Conflicts

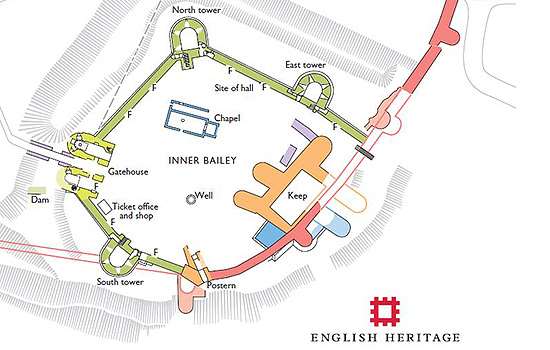

After 1230 the castle passed to a sequence of royal favourites, including Peter of Savoy, who was granted it in 1246. He was the uncle of Eleanor of Provence, Henry III’s wife. By 1254 Peter had probably replaced the inner bailey's timber defences with the present stone walls and towers. The inner bailey was the heart of the medieval castle with a chapel, a well, a great hall for communal dining, and living quarters, as well as the impressive keep.

These new defences were soon put to the test during the baronial conflicts of Henry III’s reign (1216–72). On 15 May 1264 an army led by Simon de Montfort inflicted a crushing defeat on the king’s forces at the Battle of Lewes, after which the royalist constable of Pevensey was ordered to surrender the castle.

When he refused to do so, a siege ensued. In September local knights were called upon to help stop the garrison raiding the surrounding countryside. Though parts of the Roman outer walls were damaged during the siege, ultimately the castle held out, and the siege was only finally lifted in July 1265, making it the longest siege in medieval England.

Ruin and Repair

The castle was handed back to Peter of Savoy after the king’s victory at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. On Peter’s death in 1268 it passed to Eleanor of Provence, and then descended as Crown property for about 100 years, often being given to queen consorts as part of their dowry.

Royal accounts from the 1270s onwards show that the buildings were continually on the verge of ruin despite regular and extensive repair.[10] Limited use contributed to their rapid decay, while corrupt officials also played their part. In 1306 the constable Roger de Levelande was accused of breaking up and selling the wooden bridge over the moat, and some ‘warders’ of burning the timber from a disused barn.[11] The cost of repairs was estimated at more than £1,000.[12]

Archaeological excavation has also shown that the keep was partially demolished and rebuilt in about 1325.[13]

Pevensey and John of Gaunt

In 1372 John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, took ownership of Pevensey. He refused to garrison the castle against French attacks in 1377, claiming that if it were destroyed he had enough money to rebuild it. Such actions fuelled his unpopularity and in 1381, during the Peasants’ Revolt, a mob broke into the castle, burnt the court records held there, and attacked Gaunt’s steward.[14]

In 1394 Gaunt appointed Sir John Pelham (d.1429) as constable of Pevensey. Pelham supported Gaunt's banished son, Henry Bolingbroke, when the latter returned from exile to claim his inheritance in 1399 and to usurp Richard II (r.1377–99).

After Bolingbroke landed, Pelham held Pevensey on his behalf. On 25 July 1399 Pelham wrote to Bolingbroke reporting that he was under heavy siege by local levies from three counties, and asking him ‘to give remedy to the salvation of your castle’.[15] His gamble in supporting Bolingbroke paid off: when Henry was crowned king as Henry IV, he granted Pelham the castle and honour of Pevensey in reward for his services.

Later History

During the 15th century the castle became a state prison. Among those held there were James I, King of Scotland, and Joan of Navarre, the second wife of Henry IV, who was accused by her stepson Henry V of plotting his death by witchcraft. Under the Tudors the castle fell out of use altogether, and a survey of 1573 records that the buildings were totally ruined.[16] The threat of the Spanish Armada (1588) led to the construction of a gun emplacement in the outer bailey armed with two cannons, one of which survives at the castle.

After centuries of decay, in 1925 the castle’s then owner, the Duke of Devonshire, gave the site to the State and it was repaired as a historic monument.

The events of the Second World War gave a strange twist to Pevensey Castle’s history. After the fall of France in 1940, Pevensey once more became a potential landing place for an invasion. A command and observation post was set up, the perimeter defences were refortified, pillboxes for machine-gun posts were built, and a blockhouse (for anti-tank weapons) was constructed in the mouth of the Roman West Gate. The towers of the inner bailey were refitted as barracks for the garrison, which included the Home Guard, British and Canadian soldiers and US Army Air Corps units.

The Ministry of Works supervised these alterations to ensure the new work blended with the old (and so was camouflaged). After 1945 the townspeople of Pevensey petitioned for the new works to be left in place as a monument to this important episode in the castle’s history.

Related Content

-

Visit Pevensey Castle

With a history stretching back over 16 centuries, Pevensey chronicles more clearly than any other fortress the story of Britain’s south coast defences.

-

Pevensey Castle Collection Highlights

Explore Roman and medieval finds from Pevensey Castle that reveal the everyday lives of the people who lived and worked there.

-

Joan of Navarre

Read about Joan of Navarre, who was imprisoned at Pevensey Castle in 1420 accused of witchcraft and plotting to kill the king.

-

Listen to Speaking with Shadows

In this episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast we visit Pevensey Castle, to discover the story of Joan of Navarre’s imprisonment there.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan to discover how Pevensey Castle developed from Roman fort to medieval castle.

-

Where did the Battle of Hastings happen?

Was Battle Abbey built ‘on the very spot’ where Harold fell, or was the Battle of Hastings fought elsewhere? Discover the latest thinking about the battle’s location.

-

What happened at the Battle of Hastings?

On 14 October 1066, two closely matched armies fought each other for the throne of England. Find out what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.