Context: Freedom, slavery and oppression

For people of colour living under colonial rule in the 18th-century Caribbean, life choices were limited and precarious. Most lived in slavery working on plantations owned by white Europeans, although there were also smaller numbers who were free. The free population were often the children of enslaved women and white plantation owners, but despite their freedom, they could still be subject to white authority. The institution of slavery permeated every facet of Caribbean life, and racism and discrimination were part of everyday life for people of colour. Despite this, many found ways of challenging white authority and oppression by both passive and active forms of resistance.

In 1794 slavery was abolished on the French island of Guadeloupe in the eastern Caribbean. Many slaves left the plantations but a system of low paid obligatory plantation work was maintained – work that was often undertaken by women. Many newly freed men joined French military units and fought against Britain in the war that had broken out in 1793. Participation in military service enabled former slaves to establish their identity as free French citizens and offered the prospect of a career, promotion and marriage. Opportunities that, as slaves, would have been unthinkable. Those who did not join the military were coerced for the good of the new Republic to continue working on plantations as cultivateurs with little or no pay, and very little time off.

As the idea of emancipation spread through the Caribbean, many of the newly enlisted soldiers of colour from Guadeloupe went on to fight Britain on other islands including St Lucia and St Vincent. Some were then captured as military prisoners of war and, imprisoned in Portchester Castle, they awaited their release into the turbulent theatre of war.

Follow our thread on Twitter, where you can trace some of the options available to a Caribbean person of colour at this time, and read more about some of their journeys below.

Follow the Twitter threadJourney one: Returned to slavery

It is 1794 and you have been emancipated from slavery on the island of Guadeloupe. Rather than join the military and fight against Britain, you choose to stay in Guadeloupe and work as a ‘free’ cultivateur. However, your status as a free person of colour does not last long.

As the French Revolution evolved, ideas about freedom and equal rights for people of colour began to shift back towards their pre-Revolution status. As a result, men and women of colour, including soldiers, were at risk once more of having their status as free citizens of the French Republic challenged by those who had previously owned them.

Those who did not or could not go into the French Army experienced a more restrictive form of freedom. Many were coerced into returning to the plantations to continue working on the land, often for little or no reward. The abolition of slavery had, for these workers, brought little benefit beyond the hope of change. Change was, in the end, short lived. By 1802 the political landscape had changed and Napoleon had begun to re-establish a system of slavery once more on French islands.

Journey two: Enlisted into the British military

After slavery is abolished in Guadeloupe in 1794 you choose to fight for France against Britain. You are captured and taken to Portchester Castle in England as a prisoner of war, but are discharged into the British Army.

Once imprisoned in Portchester there were opportunities for some of the Caribbean prisoners to change sides and fight for Britain. The British armed services were always in need of skilled soldiers and sailors, and prisoner of war depots provided opportunities for recruitment. We know, for instance, that a prisoner named Modeste, who was captured in St Lucia in May 1796, was discharged into the British Royal Artillery from a prison ship in July 1797.

Foreign prisoners of war, including soldiers of colour from the Caribbean, were also recruited onto the ships of the British Navy. Nelson’s flagship, Victory, relied upon foreign sailors and it is possible that some of his sailors were recruited from prisoner of war depots such as Portchester.

It’s likely that many of these soldiers would have stayed in Britain after service, perhaps starting families of their own in their new country.

Journey three: Enlisted into the French military

After several months as a prisoner of war at Portchester Castle, you are eventually released and sent to France. There you are consolidated into the Black Pioneers, a new battalion in the French military.

Towards the end of 1797, almost a year after they had first arrived at Portchester, the soldiers from the Caribbean began to be released from prison and sent to France as part of prisoner exchanges. Once in France, some may have returned to the Caribbean to continue fighting in the military campaigns there. Most remained in France, and were ordered to the Île d’Aix, off the west coast of France. On the island many had their ranks and commissions taken away and there were continual problems with providing supplies for them and paying them.

Eventually they were formed into a new fighting force, the Bataillon des Pionniers Noirs (Black Pioneers), before becoming le Royal-Africain regiment. In around 1806 they were sent to Italy to provide military support to the Kingdom of Naples, and they also fought for Napoleon across Europe and Russia.

These well trained and experienced soldiers fought and died in the Caribbean and in Europe to earn their right to be considered free citizens of the French Republic. New research is beginning to reveal that some may have settled in France, where they married and started a new life in towns and villages across France.

Journeys Four and Five: Divided Loyalties in the Caribbean

From Portchester you are sent to France, and you eventually return to the Caribbean. However Napoleon attempts to re-establish slavery on the French Caribbean islands and you have to decide whether to fight for or against France.

In 1800 two soldiers returned to the Caribbean but met with dramatically different fates. The diverging lives of Captain Louis Delgrès and Magloire Pélage demonstrate how political upheaval and changing ideologies could divide loyalties in the Caribbean at this time.

At the start of the French Revolution in 1789 both men had army careers in the Caribbean. In 1795 they fought the British on St Lucia and were promoted on the battlefield: Pélage to Chef de Bataillon and Delgrès to Captain. In May 1796 both men were captured by Britain on St Lucia and brought to Portchester along with the other soldiers from St Lucia, St Vincent and Grenada. Once released from prison they eventually returned to the Caribbean but by this time the political situation on many of the French islands was changing and the rights of people of colour were being revoked.

When Napoleon began to re-establish slavery on Guadeloupe, Delgrès and other soldiers and civilians tried to resist the changes and eventually took up arms – this time against France. On 28th May 1802, Delgrès made his last stand against the French army at Matouba, where he would have seen a familiar face among the ranks of his enemy.

Leading the military campaign against him was his former comrade in arms, Magloire Pélage. Pélage had initially stood against Napoleon too, but as the situation grew more complex he eventually decided that siding with the French was the best option.

With Pélage and the French army closing in on them, Delgrès and his followers lit their gunpowder stores and blew themselves up rather than be captured and enslaved. There is a memorial to Delgrès on Guadeloupe and an inscription honouring him in the Panthéon in Paris where distinguished French citizens are buried or commemorated.

For Pélage, fighting for France in a world of changing ideologies and witnessing the violent death of a former comrade must have left its mark. Little is yet known about his life after the war, but some years later he is recorded as living in a town to the north of Paris with his family.

Find out more

-

Black prisoners at Portchester Castle

Read the extraordinary story of a group of over 2,500 prisoners of war who were brought to Portchester Castle in 1796 from the Caribbean island of St Lucia.

-

Black people in late 18th-century Britain

How much do we know about other black people living in Britain around the time the prisoners from the Caribbean were being held at Portchester?

-

Listen to Speaking with Shadows

In the episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast, Josie Long visits Portchester Castle to learn about the black prisoners of war who were imprisoned there in the 18th century.

-

The prisoners' theatre at Portchester Castle

Find out about the theatre set up and run by French prisoners of war at Portchester Castle between 1810 and 1814.

-

History of Portchester Castle

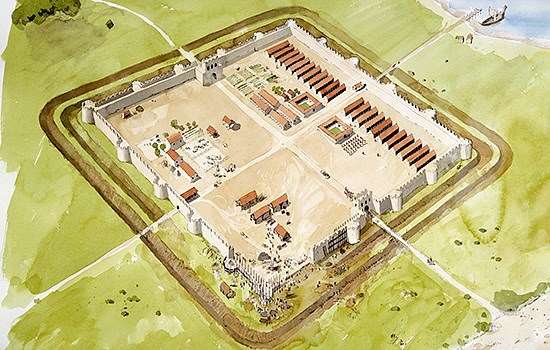

Read a full history of the castle, from its origins as a Roman fort, through its development as a medieval castle and its role as a prison, to the present day.

-

Visit Portchester Castle

Plan your visit to the castle, where you can explore the exhibition in the keep and wander around the impressive grounds on the edge of the Solent.