First World War Conscientious Objectors at Richmond Castle

How 16 conscientious objectors detained at Richmond Castle during the First World War were taken to France, and sentenced to death – a sentence commuted to ten years’ hard labour – for refusing to obey orders.

CONSCRIPTION AND CONSCIENCE IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Covering the delicate lime-washed walls of the 19th-century cell block at Richmond Castle, North Yorkshire, are thousands of graffiti. Many of these were drawn by conscientious objectors (COs) who were held at the castle for refusing to participate in the First World War on moral, political or religious grounds.

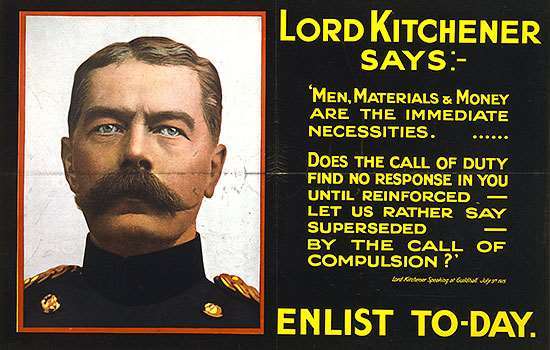

By 1916, confronted by falling numbers of volunteer recruits and high casualty rates, the British army faced a crisis in manpower. As a result, military conscription was introduced.

The conscription laws allowed men to apply for exemption from military service on the grounds of ill-health, hardship, occupation, or conscientious objection. Thousands did so. Of the relatively small numbers who applied on the grounds of conscience, however, few were granted total exemption from serving in the war. Instead, many were ordered to join the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC). This was a military unit in which they could work in support roles that did not involve fighting or the use of arms. In 1916 Richmond Castle became a base for the NCC, and COs – mainly from the Midlands and north of England – were sent there in their thousands.

Some men willingly enlisted in the NCC. But for a handful, contributing to the war effort in any way went against their fundamental beliefs. These men resisted enlistment and were often severely treated as a result. At Richmond, some were confined to barracks or detained in the castle guardroom or cells.

THE CELL BLOCK AT RICHMOND CASTLE

Originally built as a storage block in the 19th century, the cell block consists of eight small cells over two floors.

Men held in these cold, dark, cramped cells were sometimes put on a punishment diet of bread and water. Yet despite these harsh conditions, accounts written by some of the men reveal their optimism, solidarity and strong convictions. They sang hymns, recited from the Bible and debated political and religious matters. Two COs even played chess on a pocket board passed through a hole in the wall.

The most remarkable expressions of their convictions, however, are the hundreds of graffiti they left behind. The walls of their cells are covered with portraits of loved ones, religious verses, political slogans and hymns.

THE RICHMOND SIXTEEN

Among the COs detained at Richmond Castle were the men who have become known as the Richmond Sixteen. They included Methodists, a Congregationalist, a Quaker, International Bible Students (later known as Jehovah’s Witnesses), a lay reader, and socialists:

- Norman Gaudie, a clerk for the Eastern Railway, Newcastle, and reserve Sunderland FC footballer

- Alfred Martlew, a clerk at the Rowntree’s chocolate factory in York

- Alfred Myers and Charles Ernest Cryer, ironstone miners from Skinningrove, North Yorkshire

- John Hubert (Bert) Brocklesby, a schoolteacher from Conisbrough

- Leonard Renton, a draughtsman from Leeds

- Charles Rowland Jackson, a clerk at a Leeds wool merchant

- Robert Armstrong Lown, a bookseller from Ely

- Clifford Cartwright, a printer from Leeds

- Charles Herbert Senior, a carpenter and cabinet maker from Leeds

- Ernest Shillito Spencer, a clerk in a Leeds clothing factory

- the Hall brothers – Clarence, a joiner’s clerk, and Stafford, a draughtsman for Leeds Corporation sewage works

- the Law brothers from Darlington – William Edwin (Billy), a painter and decorator, and Herbert George (Bert), a share broker’s clerk

- John William Routledge, a clerk at the Leeds steel works.

SENTENCED TO DEATH

On 29 May 1916 the Richmond Sixteen were taken from Richmond Castle and, with serving members of the NCC, transported to Henriville military camp, near Boulogne, France. Once there, they were considered to be on active service, which meant that they might face a firing squad if they refused to obey orders.

After arriving at the camp, they were given 24 hours to decide whether to follow orders or risk being shot. ‘How far are you prepared to go?’ Brocklesby asked Renton. ‘To the last ditch!’ Renton replied. Soon afterwards, the men were asked to move supplies at the nearby docks, but refused. They were then court martialled and found guilty.

The day of sentencing was set for 24 June. As Senior later recalled, the army ‘made a great show of the proceedings’. Hundreds of NCC soldiers were lined up to form three sides of a square. On the fourth, the COs stood on a large platform to hear their sentences read out, one by one. Each was ‘sentenced to suffer death by being shot’ – a sentence commuted, after a short pause, to ten years’ hard labour.

ASQUITH’S SECRET ORDER

As well as the Richmond Sixteen, 19 other British COs from Harwich and Seaford sent to France during May 1916 received the same sentence.

Why were they treated in this way? These men presented an affront to military authority. It seems that some members of the War Office, as well as some commanders in the field, wanted to make an example of them by having them shot.

Yet it’s possible that the government never intended the death sentences to be carried out. In the days that followed the removal of the first group of COs to France in early May, Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, gave a secret order to the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, that no CO in France was to be shot for refusing to obey orders.

Perhaps Asquith hoped, by keeping this order from the public (and even some members of his War Cabinet), that until the men’s sentences were read out, the threat of being shot would deter further men from seeking exemption from military service.

CHANGING ATTITUDES

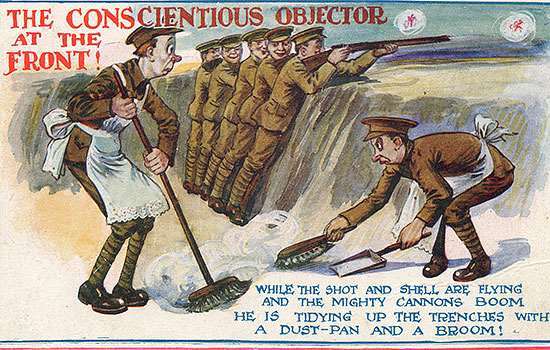

The 35 men sentenced in this way were not the last COs sent to France, and this episode did not mark the end of their harsh treatment. On their return to England, they faced years in civil prisons and work centres. Even after their release, some found it impossible to continue their normal lives in the face of hostility from local communities and employers.

Yet the publicity surrounding the Richmond Sixteen’s court martial brought to the public’s attention the dramatic lengths to which COs were prepared to go in order to uphold their beliefs, and helped to change public attitudes towards their stance.

By Dr Megan Leyland

More about the Richmond Sixteen

-

Conscription and Conscience in the First World War

Find out more about how conscription came about, and what happened to the men who applied for exemption.

-

Conscientious Objectors’ Stories

Read about the individual experiences of some of the conscientious objectors before, during and after the war.

-

Attitudes to Conscientious Objection

‘Pansies’, ‘cissies’ and ‘conchies’: find out more about how COs were treated, and how attitudes have changed since 1916.

-

Listen to the Speaking with Shadows podcast

Find out more about the Richmond conscientious objectors in this episode of our podcast Speaking with Shadows.

More First World War Stories

-

A Soldier's Letters: Pendennis to the Western Front

How one man's letters to his sweetheart offer a very special record of the Great War.

-

Blue Plaque: Edith Cavell

Read the story of pioneer of modern nursing and heroine of the First World War Edith Cavell. And discover where you can find her London blue plaque.

-

The WWI Stonehenge Aerodrome

Few of today’s visitors to Stonehenge realise that they are crossing the site of a First World War airfield, where trainee pilots honed their flying skills before being posted to the Western Front.