Augustine’s Mission

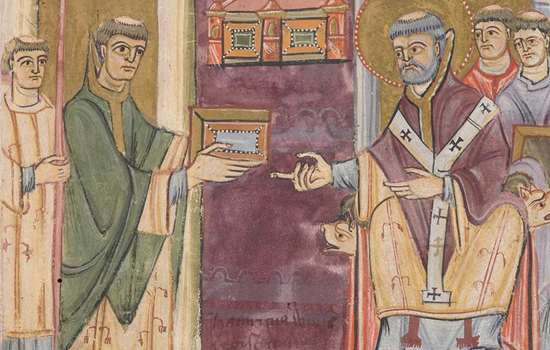

In 597 St Augustine landed on the shores of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent at Thanet. He was on a mission from Pope Gregory the Great to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Christianity had first been introduced to Britain by the Romans, but survived only in the west after the invasions of pagan peoples from northern Europe in the 5th century.

King Æthelberht of Kent was one of the most powerful men in England. While he did not immediately convert to Christianity, Æthelberht welcomed Augustine and his fellow missionaries and granted them land on the east side of Canterbury, just outside the city walls. Kent had been chosen as the starting point of Augustine’s mission in part because Æthelberht’s wife, Queen Bertha, a Frankish princess, was already a Christian. The new abbey was founded close to St Martin’s, an ancient church where Bertha worshipped.

The abbey was probably founded in 598 and consisted of an inner precinct containing the abbey’s main buildings and cemetery, and an outer precinct containing vineyards, orchards and gardens. Building of the main church, dedicated to St Peter and St Paul, started almost immediately. A second, smaller church was constructed to the east of the site and dedicated to the Virgin Mary, with a third church, built between the mid-8th and 10th centuries, dedicated to St Pancras.

The abbey was rapidly established as an important centre of learning and monks travelled long distances to study at its school.

Read more about St Augustine and his missionReforms, raids and relics

Starting in the mid-10th century, attempts were made to reform English monasticism through the adoption of the Rule of St Benedict. This was written in the 6th century by St Benedict for his monastery at Monte Cassino, near Rome. The Rule concerned all aspects of monastic life, imposing a strictly vegetarian diet and insisting that the monks should sleep together in the dormitory as a community. The monastic day was divided into periods devoted to communal prayer in the monastic church, reading and manual labour. The ethos of Benedictine monasticism is summed up by the motto adopted by the Order in the late Middle Ages: Prayer and Work.

One of the key reformers to promote the Benedictine Rule was Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury and later Archbishop of Canterbury. He greatly revered Augustine, and in 978 he changed the dedication of the church of St Peter and St Paul to include St Augustine. From this time onwards, the monastery was known as St Augustine’s Abbey.

Like many other monasteries, St Augustine’s suffered at the hands of the Vikings. In 1011, they raided Canterbury, capturing Abbot Aelfmaer and holding him hostage. Peace was restored with the crowning of the Danish invader Cnut as king in 1016. He granted important new privileges to the abbey.

Its prestige was also enhanced by the translation (moving) of the relics of the 8th-century St Mildred from Minster-in-Thanet to St Augustine’s. Mildred was the great-great-granddaughter of King Æthelberht, and the translation affirmed the historical importance of the abbey and its connections with Kentish royalty.

Norman rebuilding

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, St Augustine’s, unlike some other abbeys, was allowed to keep most of its land and possessions. However, the last Anglo-Saxon abbot, Aethelsige, was forced to resign in 1070. He was replaced by Scolland, a monk from Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy.

Both St Augustine’s Abbey church and Canterbury Cathedral were extensively rebuilt within 40 years of the Norman Conquest, in a new architectural style, now known as Romanesque, brought by the Normans from France. Scolland instigated works that saw the abbey’s three separate Anglo-Saxon churches replaced by a grand new abbey church. Over 100 metres long – about the length of a modern football pitch – it was almost two-thirds the size of Canterbury Cathedral.

By the mid-11th century, the abbey had been transformed into one of the most architecturally impressive monasteries north of the Alps.

The late middle ages

There were occasional disputes between the monks of St Augustine’s and those of nearby Canterbury Cathedral and the city’s archbishop, who wanted to assert their jurisdiction over the running of the monastery. This was bitterly resisted by the monks of St Augustine’s, whose abbots secured special privileges from the Pope guaranteeing the independence of the abbey. The abbots of St Augustine’s also received papal permission to use the mitre and other ornaments normally reserved for bishops.

The monks of St Augustine’s were very proud of their abbey’s history and fiercely defensive of its rights and privileges. These were detailed in chronicles, or histories, of the monastery, several of which survive including that of William Thorne, a monk of St Augustine’s in the 1390s.

The late Middle Ages also saw an increase in the number of monks living and worshipping at the abbey, from 61 monks in 1146 to 84 in 1423, a very large community for the time.

There were sustained building works at the abbey, including the construction of an impressive new Lady Chapel between 1496 and 1510, which was added to the east end of the church. The monks remained deeply devoted to their founding saint and in 1530 published a pamphlet describing the miracles associated with him.

The monks cannot have guessed that within a decade, almost 1,000 years of monastic life at their abbey would have been brought to an end, with many of its buildings reduced to ruins.

Suppression

In 1535, King Henry VIII broke with Rome and declared himself head of the Church of England after the Pope refused to grant him a divorce from Katherine of Aragon. The riches of the monasteries were soon in Henry’s sight, resulting in the Suppression of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1540.

The end for St Augustine’s came on 30 July 1538. Perhaps mindful of the brutal execution of the small number of abbots and monks who resisted the closure of their monasteries, the monks of St Augustine’s offered no resistance. Abbot John Essex and his 30 brethren signed the document voluntarily surrendering the abbey to the king. The abbot was awarded a generous pension and retired to a former manor of his monasteries. The monks also received pensions, with many also finding works as parish priests.

Several of the abbey’s buildings were rapidly reduced to ruin. Everything of value was seized by Henry’s henchmen, including silver-gilt images of St Augustine and King Æthelberht (by then venerated as a saint), and a reliquary containing part of Æthelberht’s skull. The shrines of St Augustine and the abbey’s other saints were destroyed, as were the tombs of the Anglo-Saxon kings of Kent who were buried in the church. The abbey’s magnificent library was dispersed, and although 283 volumes survive, they represent a small fraction of the books once in the abbey’s possession.

A Royal Palace

In 1541, Henry personally ordered the demolition of the abbey’s church. But not all the abbey’s buildings were targeted for destruction. From 1539, the former abbot’s apartments were converted into a royal palace. Renovation of the site took over a decade to complete and included the construction of a walled courtyard and a private garden. Nevertheless, St Augustine’s never gained favour as a royal residence and by 1564 it was being let to nobles and gentry.

In 1612, the site was sold to Edward, Lord Wotton, a prominent figure at the court of James I. Wotton employed the noted gardener John Tradescant the Elder to lay out three ornamental gardens to the north and east of the palace.

When Wotton’s widow died in 1658, the palace and gardens were inherited by his great-grandson Sir Edward Hales, a trusted companion of the future James II. The abbey would remain in the Hales family until 1804–5.

During the Wotton and Hales occupancy, some of the buildings of the abbey decayed and their use changed. The chamber over the Great Gate was used for cockfighting with other parts of the building turned into an inn called the Old Palace. In 1793 a poorhouse was built within the medieval lay cemetery, and a new gaol was built in the same location in 1808.

St Augustine’s College

In the 1840s, most of the site was purchased by Sir Alexander James Beresford Hope, a politician and art collector. Beresford Hope formed a partnership with Edward Coleridge, a master at Eton, to establish a missionary college on the site of St Augustine’s.

William Butterfield, who would later be hailed as one of England’s great Gothic Revival architects, was appointed to design the college buildings. During their construction, some of the abbey’s medieval remains were revealed and archaeological exploration of the site was started, with periodic excavations continuing until the 1980s.

St Augustine’s College operated from 1848 until 1947, when its buildings were let to the King’s School. In 1938, the Office of Works (a predecessor of English Heritage) took over guardianship of the site, allowing public access to the areas not then privately owned. In 1989, UNESCO declared St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury Cathedral and St Martin’s Church a World Heritage Site, in recognition of their importance to the history of Christianity in England.

Find out more

-

Who was St Augustine?

In the late 6th century, a man was sent from Rome to England to bring Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons. But who was St Augustine, and how did his mission succeed?

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of St Augustine’s Abbey to discover how its buildings developed over time.

-

Monasteries and abbeys

Learn more about England's medieval monasteries and abbeys and uncover the stories of those who lived and prayed in them.

-

A mini guide to medieval monks

Do you know the difference between the Benedictines, Cluniacs, Carthusians and Cistercians? This short animation will guide you through the different religious communities in medieval Britain.