The Bobbin Industry

Lake District bobbin making began in the 1780s[1] and flourished throughout the 19th century. Its expansion was driven by the rapid growth of the Lancashire textile industry, for which the wooden bobbins – the spools or reels around which yarn is wound – were vital. Over the course of the century more than 100 bobbin mills went into production, peaking in about 1860, when about 60 mills were active.

The remote and rural Lake District provided the industry with the resources it needed. Water power was readily available, and transport routes already existed for the export of iron. Coppiced woodland – small trees regularly trimmed back to encourage the growth of long, straight poles – was the characteristic feature of the local landscape, and coppice poles were the industry’s main raw material throughout its history.

Mills generally acquired their supplies of poles from within a 20-mile radius. The poles were bought as a standing crop and then seasoned (dried) at the mill for about a year before use. The most common species of wood used were alder, ash, birch and willow.

A Speculative Venture

Some bobbin mills were converted textile or corn mills, but others were specifically built for bobbin manufacture.[2] Stott Park was a speculative venture by the local landowner, John Harrison, of The Landing, near Lakeside. When it was first advertised to be let in late 1835, it was described as ‘newly erected’,[3] although as the adjoining coppice is called Smithy Haw Wood it is possible that the site had been used before for ironworking.[4]

A series of advertisements specified that the mill could house 25 to 30 lathes.[5] Harrison sought a tenant who would provide the tools, labour and stock in trade, and would bear the risk of taking the mill into production. A house was available if needed.

The next 30 years saw a succession of tenants, or bobbin masters, take on the lease for relatively short periods.[6]

The Early Bobbin Masters

John Harrison, Stott Park’s owner,[7] was a well-established yeoman (a small landowner), whose family had lived for generations in Furness, then part of Lancashire.[8] On his death in 1843[9] the estate passed to his brother Myles,[10] then to Myles’s widow, Elizabeth, in 1848, and in turn to her grandson, Thomas Newby Wilson, who died in 1917.[11]

By contrast the bobbin masters were generally artisans or tradesmen, and the Stott Park tenants came from local manufacturing families. The lessee until 1839 was named Rushworth,[12] followed by James Bethom during the 1840s[13] and then his cousin William Wharton, who died in 1855.[14]

Take a virtual tour of Stott ParkThe mill and the Coward family

Thomas Eyers, the bobbin master until 1864, began the mill’s connection with the Coward family of Skelwith Bridge, near Ambleside. Eyers was conspicuously upwardly mobile, having married Susannah, Jeremiah Coward’s second daughter, when he was a journeyman bobbin turner at the Cowards’ Skelwith Bridge bobbin mill.[15]

Jeremiah Coward was an astute businessman who owned the Hare and Hound inn (now the Skelwith Bridge Hotel) and a corn mill as well as two bobbin mills.[16] His son John ran the family bobbin mill business at Skelwith Bridge. When John died suddenly in 1858 aged 44, Jeremiah advertised for tenants, but apparently the mills then stood idle for some time.[17]

In 1864 Thomas Eyers gave up the Stott Park lease in order to buy a large bobbin mill at Crooklands.[18] John Coward’s widow, Elizabeth, and her elder son, William, who had been a clerk in the Skelwith Bridge bobbin mill, moved to Stott Park and took on the lease there from Eyers. Elizabeth and her two sons initially lived in Bobbin Mill House.[19]

When William died in 1882 his younger brother, John, succeeded him as bobbin master and ran the business rigorously until the early 1900s. He lived at Plum Green in Finsthwaite village until moving to The Copse, a nearby house he had built in 1903.[20]

Expansion

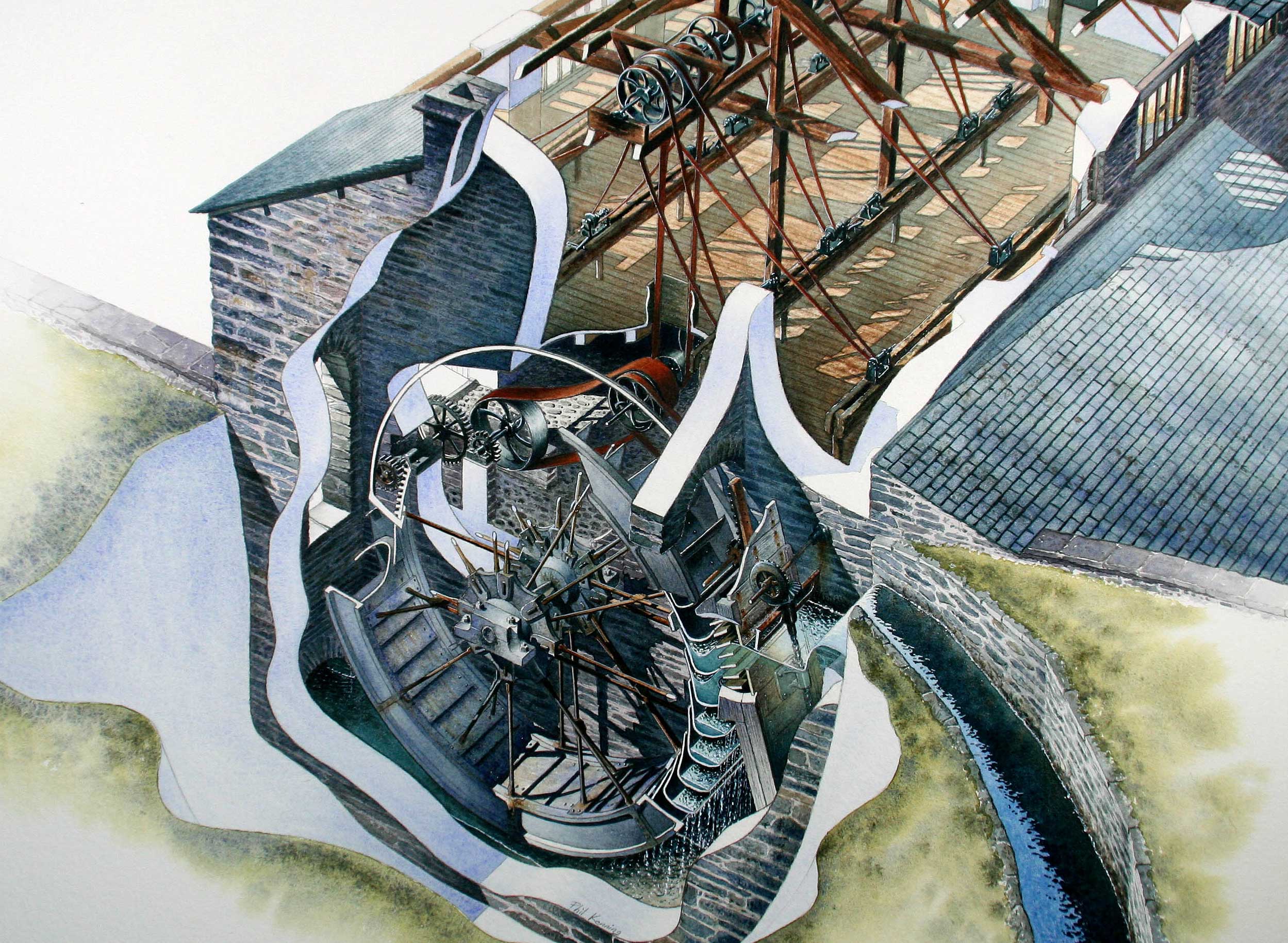

In 1858 the mill’s waterwheel was replaced – after more than 20 years’ use it would have been worn out. It had been fed by a pond beside the mill, which drew its water from High Dam, an artificial tarn half a mile north-west.[21]

The wheel was replaced by a water turbine, newly invented and more efficient. The old pond was filled in and a new header pond created to provide greater water pressure.[22]

At about this time the bobbin manufacturers faced a series of challenges from which many never recovered. First, there was a severe drought in 1859, which stopped many mills for weeks. Secondly, a government inquiry during the 1860s led to the regulation of child labour – on which the mills depended heavily – pushing up labour costs. Finally, the Lancashire Cotton Famine (1861–5) badly disrupted the bobbin mills’ main market.

At Stott Park, the Cowards responded by modernising. In 1876 the owner enlarged the mill by building two coppice barns and a new lathe shop[23] to house more modern machines. These were heavier and faster, and had to be fixed to the ground.

When the lathe shop came into use, however, it seems that there was not enough power to drive these new machines. By the early 1880s a steam engine had been installed to supplement the turbine’s output when needed.[24] Water then remained the primary source of power in the mill right up until 1941, when the first electric motor was installed.

Diversifying

By the 1890s, when the textile industry standardised its requirements, one fully automatic bobbin machine could equal the output of a whole mill.[25] Stott Park, however, after the expansion of the 1870s, did not modernise by converting to these machines. Its lathes and saws continued to be driven by belts from line shafting.[26]

Under this system a revolving shaft, originally powered by a waterwheel, was connected to each of the machines by an unguarded leather belt. This form of power transmission was commonly used in factories in the 19th century, though it had the disadvantage of causing a total stoppage for maintenance or malfunction.

The original turning and boring lathes had required the use of considerable judgement by a skilled operator. However, the new lathe shop housed lathes that had pre-set operations and semi-automatic borers, as well as a new type of machine known as the blocker or blocking machine.[27]

During most of the 19th century the staple products of the mill were small bobbins and pirns (used for spun yarn), which were turned from a single cylindrical length of coppice (a ‘block’), and reels or larger composite bobbins made up from a shank to which two ends were glued.

Ironically, Stott Park survived because its old-fashioned machines could be adapted to make alternative products when demand for bobbins fell away. By 1900 ‘spout washers’,[28] duffle-coat toggles, yarn and wire reels and tool handles were its main products.[29]

The Workforce

The key workers at the mill were apprentices and bobbin turners, supported by sawyers and labourers. When apprenticeships died out in the early 20th century, production relied on the skilled bobbin turners or journeymen.

Until the introduction of the Factory and Workshop Act of 1878, boys as young as eight were employed in the mills. After the Act was introduced, 10 years old was, in theory, the lowest age at which work was permitted, and then only half-time up to age 14, to allow attendance at school. The boys worked up to 16 hours a day in often repetitive manual tasks.[30]

At 14, youths were indentured to serve a seven-year apprenticeship – a very long time considering the limited range of skills required. Apprenticeships were popular with the masters, however, being a source of labour that was both cheap and captive. Apprentices could be released before their time only by a magistrate, and the punishment for running away could be severe.[31]

In the 1870s Stott Park was one of a number of local mills which indentured boys from Ulverston workhouse. This created a local scandal when a member of the workhouse board of guardians accused the bobbin masters of mistreating the boys.[32] However, calls for a government inspection went unheeded.

read more about child labour in the Lake DistrictLiving conditions

Young men became journeyman bobbin turners when they completed their apprenticeship. Throughout the 19th century they worked mainly on the finishing lathes, and were paid for what they produced.[33] At Stott Park the numbers of bobbin turners varied over the years.[34] The mill was a male preserve, although one female worker is recorded in the 1890s.[35]

As the composition of the workforce changed, so too did their living arrangements. For most of the 19th century apprentices and unmarried journeymen lived with the bobbin master and his family at Bobbin Mill House. By the 1850s the married journeymen were living in cottages rented from the Harrison estate at Plum Green, Finsthwaite.

John Coward started buying these properties in 1868,[36] and his tenants were obliged to use his shop there, which was run by his sisters, Margaret and Eliza.[37] At least six families were established at Plum Green by the 1890s, while Bobbin Mill House had been split among four households, one of them Elizabeth Coward’s. The unmarried men now found lodging with families.[38]

Later years and conservation

Until the outbreak of war in 1914 the mill was sending products as far afield as India. During the war the Admiralty was a major customer for duffle-coat toggles. The old-fashioned machinery was flexible and could produce short runs of a wide variety of simple products, enabling it to remain in business until the use of plastics became widespread in the 1960s.

In 1917 the estate owner, Thomas Newby Wilson, died without heirs. In 1921 the Cowards bought the mill, including High Dam, from the estate’s trustees. They began selling off the Plum Green cottages in the 1920s,[39] and the family eventually moved away from the village, to Cartmell Fell.

Jack Ivison, who had started work at the mill in 1927, was left as managing partner and was still living in Finsthwaite when the mill closed in 1971. He enthusiastically supported the mill’s preservation. By now the buildings were in a poor state – two coppice barns had to be demolished, and all the machines had to be dismantled and moved out of the main buildings to enable the roofs to be repaired. During this time Ivison recorded his experiences of working at the mill, together with detailed descriptions of the working of each machine and the mill itself.[40]

The Department of the Environment opened Stott Park to the public as a working mill in 1983, enabling visitors to appreciate this vanished Lakeland industry. It passed into the care of English Heritage in 1984, and research into the working of the mill and its people continues.

About the author

Peter White OBE FSA was the Inspector of Ancient Monuments who recommended the purchase of Stott Park Mill for preservation in 1971 and was a member of the project team that restored the mill for public access. He continues to research the history of the bobbin industry.

Find out more

-

Plan your visit

Experience the Industrial Revolution brought to life at the mill, where you can see demonstrations of bobbin making as part of a guided tour.

-

Walk from Stott Park to High Dam

Use our walking guide to take a 4-mile circular walk from Windermere around Stott Park Bobbin Mill and the dam that powered it.

-

Spotlight on Stott Park

Discover what makes Stott Park – the only working bobbin mill left in the Lake District – so different from other English Heritage sites.

-

Buy the guidebook

This guide provides a full history and tour of Stott Park, and investigates the lives of the men and boys who worked there.

-

Feeding the Textile Industry: From Coppice to Bobbin

Explore Stott Park Bobbin Mill with this virtual tour on Google Arts and Culture.

-

Child Labour in the Lake District

Find out more about the ‘bobbin boys’ who worked at the Lakeland bobbin mills in the 19th century.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites and who made them what they are today.