The early history of Totnes

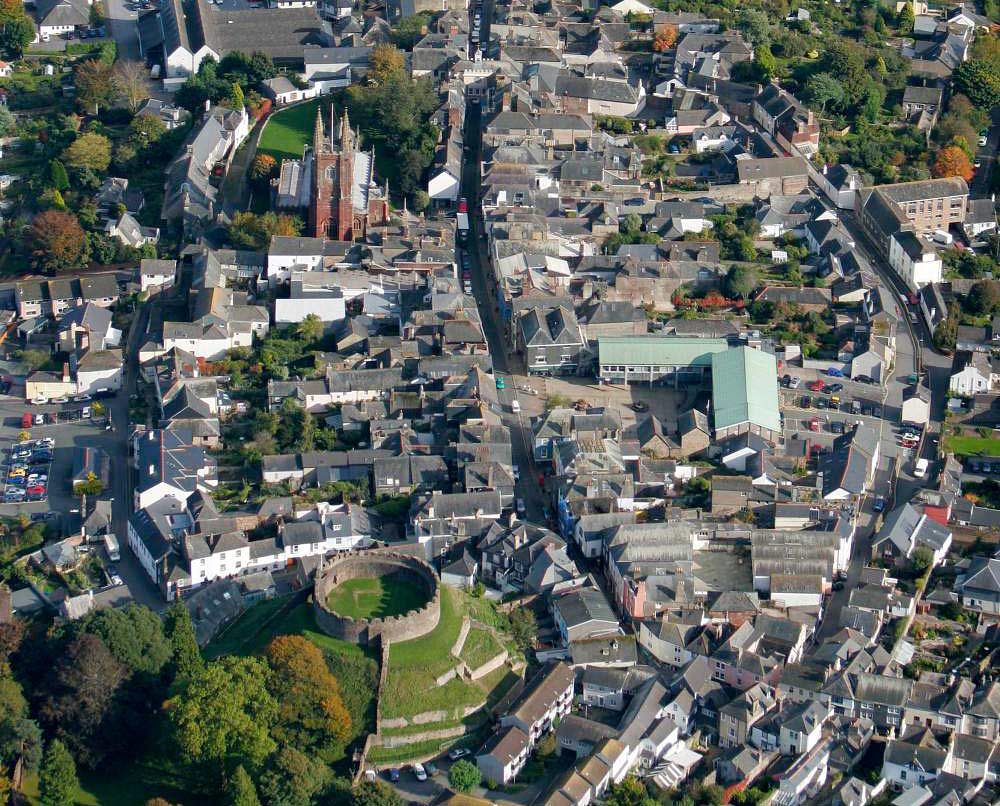

Totnes is the lowest bridging point of the river Dart and the highest point that sea-going ships could reach. Its name refers to a ‘nose’ or promontory – a high ridge along which the main street descends to the crossing-point.

According to the 12th-century historian Geoffrey of Monmouth, Totnes was the first landing-place of Brutus, legendary founder of the kingdom of Britain and descendant of a prince fleeing from the fall of Troy. A granite boulder, now set in a pavement in Fore Street, has been claimed since the 16th century as the place where he first commanded the foundation of the town.

The earliest genuine history of Totnes is obscure, but it is likely that a settlement existed in the Iron Age and Roman periods. Roman materials have been found in the area of the castle.

From the 10th century, the town’s history is better known. Totnes was one of four burhs – fortified settlements offering protection from Viking raiders – in Devon. By the mid 10th century it possessed a mint, issuing coins, and in the early 11th century was a place for royal assemblies, though its mercantile economy was in decline.

The town’s layout above the East Gate still bears the imprint of late Anglo-Saxon planning, with narrow property plots on either side of the High Street, contained within curving boundaries to north and south. The castle, established at the town’s highest point, disrupts this plan, proving that it was imposed on a town that already existed.

The motte-and-bailey castle

The foundation of the castle was a direct consequence of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. William the Conqueror gave one of his supporters, Judhael of Brittany, a large estate in Devon, with Totnes as its chief town, and it was Judhael who established a castle there. He also founded a Benedictine priory where St Mary’s Church now stands.

Probably from the outset, the castle took the form of a ‘motte-and-bailey’: a high conical mound, or motte – thought to be a natural outcrop, artificially heightened – and a larger enclosure on level ground below it (the bailey), in which the castle’s principal buildings, such as the hall, chambers, chapel and kitchens, were sited. The deep ditches around the north side of the bailey were probably first excavated as part of the initial construction of the castle. There was formerly also a ditch around the motte, though this has since been filled in.

The first defences of the bailey, and on top of the motte, were built in timber. The stone walls of the bailey and the ‘shell-keep’ (a circular or oval wall enclosing a courtyard and buildings, on the summit of a motte) were later medieval replacements. Excavation in the 20th century, and comparison with other castles, suggest that originally the motte was crowned with a tall timber watchtower, protected within a timber palisade – a high wooden fence, composed of upright beams.

More than 950 years after its foundation, Totnes Castle remains one of the most imposing castles in England, as its Norman and later lords intended it to be.

Move the sliding bar to compare a reconstruction of the castle and town as they may have looked soon after the castle was first built (left) with how they had probably developed by the 14th century. By the later date the castle had been rebuilt in stone, the town had grown, the Dart had been bridged, and a tidal inlet in the river had been drained to form farmland. © Historic England (illustrations by Ivan Lapper)

Totnes Castle in the Middle Ages

The story of Totnes Castle is not one of sieges or captures, and throughout the Middle Ages it performed essentially peaceable roles in the government of its district.

It was presumably here that rents were paid to the lord, and offenders were tried and imprisoned. Documents relating to the lordship of Totnes frequently mentioned the castle: tenants were obliged to supply bread, wine and ale for the lord’s use, provide men to guard the castle, and pay for repairs to a specified number of battlements on the castle wall.

The castle changed hands several times, either because a lord fell out of royal favour, or more often because the lord’s family had no heir. Thus the castle was held through the 12th century by the Nonant family; by the Briouze and Cantilupe families through the 13th century; and the Zouches, a Northamptonshire family, until 1485.

Occasional descriptions reveal a castle in disrepair, presumably little used, because its owners had other more comfortable residences elsewhere. In 1273, a survey revealed that the hall, chamber and chapel in the bailey were weak or ruinous, the stone walls around the bailey were in the same condition, and the stone defences on the motte were near to collapse.

In the 1320s, William, 1st lord Zouche, replaced the derelict structure on the motte with the shell-keep we see today. In 1326, Lord William had supported the nobles who deposed Edward II (1307–27) and imprisoned the king at Kenilworth Castle. It may have been the political instability at the end of Edward’s reign that encouraged Lord William to strengthen Totnes with this new shell-keep.

The stone wall protected one or more buildings inside, standing beside an open courtyard. Evidence can be seen for a building against the wall, on the north-west side. The wall is capped with battlements and a wall-walk, allowing defenders to shoot in all directions.

But in time, the castle again became neglected. By the late 15th century it was reported that the motte was overgrown with trees and shrubs.

A declining castle in a thriving town

After the accession of Henry VII as the first Tudor king in 1485, Totnes was awarded to the Edgecumbes, who had supported him against King Richard III. Once again, nothing was done to repair the castle, which by 1538 contained no intact buildings. But even though the castle was no longer habitable or defensible, tenants in the region still held property nominally in exchange for services to it: its survival was required almost as a legal fiction, as it underpinned the whole system of land tenure.

In the mid 16th century the castle was sold to a Totnes merchant family, and it was then sold again in 1591 to the Seymour family, owners of the nearby castle at Berry Pomeroy.

The proximity of Berry Pomeroy, which the Seymours were converting into a fashionable and comfortable residence, made it even less likely that Totnes Castle would return to favour.

But this was the period when the town of Totnes reached its zenith, as merchants exported commodities such as cloth and tin to France and Spain. Some of their profits were used to rebuild numerous houses in the town centre, and civic buildings such as the Guildhall, which occupied part of the site of the medieval priory. Many surviving buildings on Fore Street and the High Street date to this period.

This prosperity was short-lived, however, and by the end of the 17th century exports from Totnes had shrunk considerably.

Later history

After the 18th century, the castle was solely an ancient monument and place of recreation. Trees were planted around the site, and a gently sloping path was created to the top of the motte (replacing the steep direct stairway of the Middle Ages). The castle was only formally opened to the public as a pleasure-ground in the 1920s, with facilities for selling cream teas, and a tennis court in the bailey.

By 1947, the historic stonework of the castle was threatening to collapse in parts of the site, and the Duke of Somerset placed the ruins in the guardianship of the Ministry of Works. The motte was restored to its medieval appearance, without trees, and archaeological excavations took place in various locations, notably the top of the motte. Here the archaeologists found the base of a watchtower, which was probably built in the 11th century when the castle was newly established. Investigations in the bailey suggested that the remains of important buildings may survive below the lawn, though this has not yet been pursued.

Since 1984, Totnes Castle has been under the care of English Heritage.

Related content

-

Visit Totnes Castle

Get great townscape views from this lofty Norman castle

-

Download a plan of the castle

Download this pdf plan to see how the castle buildings have developed over time.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook explains the castle’s history and provides a tour of the castle remains, together with an outline of the town’s development.

-

Berry Pomeroy Castle

Find out more about the history of nearby Berry Pomeroy Castle, once owned by the most powerful man in England.

-

BERRY POMEROY TO TOTNES CASTLE WALK

Download this walk itinerary to guide you on a 4-mile walk through gorgeous countryside between Berry Pomeroy and Totnes castles.

-

Medieval Castles

Discover the stories held within the walls of England’s greatest fortifications and learn about the rise and fall of the medieval castle.

Further reading

S Brown, Totnes Castle (London, 1998)

SE Rigold, Totnes Castle (London, 1952)

SE Rigold, ‘Totnes castle: recent excavations’, Transactions of the Devonshire Association, 86 (1954), 228–56

S Toy, ‘The Round Castles of Cornwall’, Archaeologia, 83 (1933), 203–26

HR Watkin, History of Totnes Priory and Medieval Town, 2 vols (Torquay, 1914)