Medieval Religion

William the Conqueror imposed a total reorganisation of the English Church after the conquest of 1066. He had secured the Pope’s blessing for his invasion by promising to reform the ‘irregularities’ of the Anglo-Saxon Church, which had developed its own distinctive customs. The Church was a pervasive force in people’s lives, with the power and influence of the Catholic Church – then the only Church in western Europe – reaching its zenith in England in the Middle Ages.

The Norman church

William I’s reforms of the church were almost as much of an instrument of conquest as his knights and castles.

Within a decade nearly all Anglo-Saxon bishops and abbots had lost their positions to Normans. Even native saints came under attack, as some churches were rededicated to Norman favourites – although certain saints, such as Cuthbert, Swithun and Etheldreda, were to some extent adopted by the invading force.

The century and a half after the Conquest also saw a campaign of church, cathedral and monastery building on a scale never before seen in England.

Monastic revival

Existing English monasteries, such as Muchelney Abbey, Somerset, were reformed on Norman lines, and many new monasteries were established. In the north, Lindisfarne Priory, Tynemouth Priory and Whitby Abbey were refounded on monastic sites abandoned during 9th-century Viking raids. These monasteries belonged, like prestigious Battle Abbey in the south, to Benedictine monks, initially the only religious order in England.

The monastic life appealed to a wide range of people. Those who embraced it included aristocrats and knights, a retired ‘pirate’ (St Godric of Finchale Priory, who kept adders as pets), and the illiterate peasants permitted to join the Cistercian order as ‘lay brothers’.

As enthusiasm spread, so from the late 11th century did the Cistercians and other new religious orders, which often set out to reform the practices of their predecessors. Each offered its own version of communal living.

New orders

Cistercian ‘white monks’ (named after the colour of their habits) established, as their rule demanded, monasteries ‘far from the haunts of men’. These included Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire, which by the 1160s housed 650 monks. The plainness of early Cistercian architecture reflected the austerity of their lives. But other monastic orders allowed more elaborate decoration, as at Cluniac Castle Acre Priory, Norfolk, and Wenlock Priory, Shropshire.

‘Canons regular’ were communities of priests who often ministered as vicars of parish churches. The early 12th century saw a huge surge in the popularity of communities of Augustinian ‘black canons’, such as Kirkham Priory, North Yorkshire, and Lanercost Priory, Cumbria.

Little Mattersey Priory in Nottinghamshire is one of the few surviving relics of the only exclusively English order, the Gilbertines. Some of their other foundations were ‘double monasteries’, housing both men and women.

Quite distinct from monks because they worked ‘in the world’ (rather than abbeys and priories) were the four orders of friars: the Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Augustinians. They were inspired by the teachings of St Francis of Assisi to commit to a life of evangelical poverty, living among the poor.

In the later medieval period few new monasteries were founded, with the exception of those of Carthusian hermit-monks, such as Mount Grace Priory, North Yorkshire, in 1398. But despite the crisis of the Black Death, many older monasteries revived and thrived, often commissioning lavish new building works.

The Crusades

Different again were the military orders, the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, whose English properties essentially financed their activities in the Holy Land.

Both were born out of the Crusades, which began in 1095 and in which many Englishmen took part. Though ultimately unsuccessful in their stated goal of wresting Jerusalem from its Islamic rulers, the Crusades had a profound impact on many aspects of life and thought in western Europe. Returning crusaders brought back from their travels new ideas about architecture, health and science.

Belief and prayer

For most people, however, the parish church was the focus of religious life. Here they heard Mass each Sunday and celebrated the many saints’ days and festivals interwoven with daily life and the agricultural year. Church rituals marked life events from cradle to grave, and the local parish church dominated the spiritual – and indeed physical – landscape for the vast majority of ordinary people.

Some might bequeath money for the priest to pray for their souls after death. They hoped that prayer might shorten their time in Purgatory, where souls not condemned to Hell were ‘purged’ of their sins until they were fit for Heaven.

The wealthy could endow permanent chantry chapels (like the splendid Percy Chantry at Tynemouth Priory, Tyne and Wear, and the chapel at Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset). Chantry priests were employed solely to pray for the salvation of these benefactors and their families

Pilgrimage

Many people similarly hoped to achieve spiritual merit or cures for poor health by making pilgrimages to holy shrines. For others, like some of the tale-tellers immortalised in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, pilgrimages were an excuse for an enjoyable outing.

The goal of Chaucer’s characters was the most renowned English shrine: that of St Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral, where he was martyred in 1170. Pilgrims flocked to it from all over Britain and Europe.

This was part of a wider pattern of pilgrimage across England, often to places claiming to house saints’ relics. Hailes Abbey, Gloucestershire, boasted no less a relic than a phial of the supposed Blood of Christ. The ‘Holy House of the Virgin Mary’ at Walsingham in Norfolk brought prosperity to monasteries like Castle Acre Priory and Binham Priory, as pilgrims sojourned along the ‘Walsingham Way’.

Dissent and heresy

Those who disputed the Church’s teaching were seen as heretics, while other faiths were barely tolerated. During anti-Semitic riots in 1190, the Jews of York took refuge in the royal castle where Clifford's Tower now stands. Many took their own lives instead of risking them with the mob outside, and then set fire to the castle; the few who survived were murdered by the rioters. A century later Edward I expelled all Jews from England.

Though many complained about the clergy, few in England openly questioned the Church’s teachings until the later 14th century.

The Oxford academic John Wycliffe (d.1384) famously denounced the Church’s possessions and influence. He questioned un-biblical beliefs in Purgatory, pilgrimages and the cult of saints. Most crucially, he also disputed the power of priests to create the Body and Blood of Christ at Mass.

Wycliffe also pioneered the hitherto forbidden translation of the Bible into English, and though contemptuously nicknamed Lollards (meaning ‘mumblers’), his ‘heretical’ followers initially gained some support in high places. This prompted an alarmed Church to pass the law De Heretico Comburendo in 1401, allowing obstinate heretics to be burned. And after an abortive Lollard conspiracy in 1414 failed to kidnap Henry V at Eltham Palace in Greenwich, heresy was equated with treason against the state and lost all political credibility.

Not until the Reformation under the Tudors did the state itself overturn the power of the Catholic Church in England.

Medieval stories

-

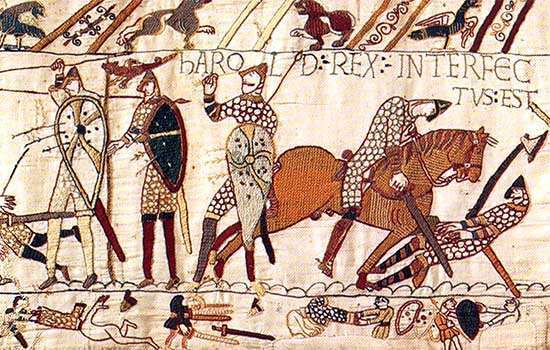

What Happened at the Battle of Hastings?

In the early morning of 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Find out what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

Piers Gaveston and the Downfall of Edward II

Discover how Edward II’s reliance on his ‘favourites’ and possible lovers led to his abdication and death.

-

The Massacre of the Jews at Clifford's Tower

One of the worst anti-Semitic massacres of the Middle Ages took place in York in 1190. The city’s entire Jewish community was trapped by an angry mob inside the tower of York Castle.

-

Lord Hastings, Richard III and an Unfinished Castle

How William Lord Hastings’s ultra-fashionable castle at Kirby Muxloe, Leicestershire, was left incomplete following his summary and shocking execution by the future Richard III.

-

Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Why did Richard, Earl of Cornwall and one of the richest men in Europe, swap three castles for a rock?

-

Where Did the Battle of Hastings Happen?

Historians have long accepted that Battle Abbey was built ‘on the very spot’ where William the Conqueror defeated King Harold. Is there any truth in claims that the battle took place elsewhere?

-

The Misbehaving Monks of Hailes Abbey

Visitation records from abbots who came to inspect Hailes Abbey offer tantalising glimpses into the lives of the monks who lived there and the vices that may have tempted them.

-

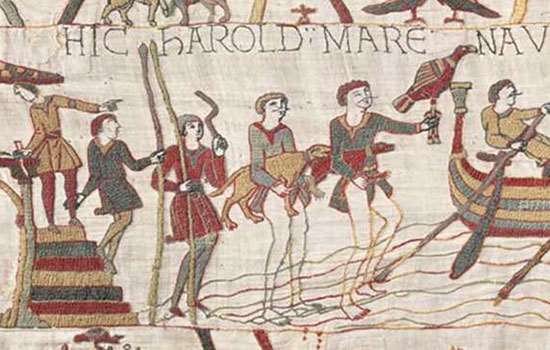

A Canterbury Tale: The Bayeux Tapestry and St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine’s Abbey has long been celebrated for its contribution to English Christianity. But could it also be the birthplace of one of the most famous artefacts in history?

More about medieval England

-

Medieval: Architecture

For more than a century after the Battle of Hastings, all substantial stone buildings in England were built in the Romanesque style, known in the British Isles as Norman. It was superseded from the later 12th century by a new style – the Gothic.

-

Medieval: Religion

The Church was a pervasive force in people’s lives, with the power and influence of the Catholic Church – then the only Church in western Europe – reaching its zenith in England in the Middle Ages.

-

Medieval: Warfare

The Norman Conquest was achieved largely thanks to two instruments of war previously unknown in England: the mounted, armoured knight, and the castle.