Invention and Importance

Bathing was central to Roman life in a way that is quite different from today. Roman bathing was communal. Families, friends and communities spent time together in bath-houses containing shared baths and rooms heated to different temperatures. They were built first in the 3rd to 2nd centuries BC in Campania (the area around Naples), a cultural melting pot of Roman, Etruscan and Greek cultures. They had became a common sight in Rome by the 1st century BC and spread across the empire.

By the time the Romans conquered Britain from AD 43, bathing was practised by men and women at all levels of society including the enslaved. As a result, bath-houses have been discovered by archaeologists across Roman Britain, from the large public baths of towns and cities, to the private bathing suites of the Roman elite. Even the forts along Hadrian’s Wall had their own baths, so the soldiers who protected the frontier could bathe in the same way as Romans living in the city of Rome itself.

Why did the romans bathe?

A trip to the baths was ideally something a Roman might do daily, although it depended upon their status. For the wealthy, the working day was over by lunchtime, so there was plenty of time for a leisurely visit to the baths in the afternoon. It might be more difficult for those who worked long hours – the poor and enslaved – who might only get a chance infrequently.

The Romans regarded bathing as essential for many reasons. They believed that there was a close connection between bathing and health. Experts often recommended bathing to prevent illness, and medical practitioners prescribed different types of bathing to treat specific ailments. The great Roman orator Cicero once wrote that bathing was one of ‘the necessities for life and health’.

Bathing was also socially important: the bath-house was where one met friends and socialised but also made an important statement of one’s ‘Romanness’. In the minds of the Romans, bathing marked an important difference between themselves and non-Romans, whom they considered to be ‘barbarians’. The emperor Justinian’s Digest – a codification of the laws of the empire – defined a Roman’s home as the place where ‘one conducts business, visited the forum and the theatre, celebrates religious festivals, and goes to the baths’. Bathing was fundamental to Roman identity.

This mosaic from the Roman Piazza Armerina in Sicily depicts women playing a number of different sports such as discus, ball-throwing and running. Exercise was an important part of Roman daily life and was generally followed by a visit to the baths

© Julian Money-Kyrle / Alamy Stock Photo

Bathe like a Roman

Roman bathing followed a specific process. Bathers would get undressed and then progress from an unheated room (frigidarium) to a warm room (tepidarium) and then to a hot room (caldarium) before heading back to an unheated room and taking a refreshing cold plunge. Bathers wore special bathing clothes and carried a toilet kit that included bottles of oil and curved metal blades called strigils for scraping oil and dirt from the skin.

In a smaller bath-house a single suite of rooms might be the extent of the experience, but larger bath-houses allowed bathers a choice of different types of heat. Sudatoria, for example, were dry sweating rooms like a modern-day sauna. In addition, there might be separate changing rooms, indoor and outdoor exercise facilities for ball games and wrestling, and even a swimming pool.

The process itself could be quite quick, but much like in a spa or a Turkish bath today, those who had the time or were enjoying the company might spend hours enjoying the heat of the baths. There were also plenty of other services on hand. Massages were common and popular, and body treatments like depilation (hair removal) were a must. Roman accounts recommend the baths as the place to discuss literature and philosophy, and also describe entertainment, such as poetry readings, and refreshments being delivered in the bath-house.

The Hypocaust System

The crucial component of Roman bathing was heat. Heating in the bath-house was achieved through a system called a hypocaust (literally ‘a place heated from below’). This was probably invented in the 1st century BC and used for baths but also other spaces, such as the reception rooms of Roman homes.

Rooms that required heating had the floor raised up on stacks (called pilae), usually of stone or ceramic tiles. This created a basement cavity into which heat was fed by a furnace (praefurnium) via a stokehole. The hottest room, kept at roughly 40°C, was normally directly joined to the furnace so it would get the most heat. The warm tepidarium, usually about 30°C, was further away and slightly cooler, since the air had further to travel. The furnace could also warm a water tank to feed the hot bath, which was often positioned directly above the point at which the hot air entered the building so the bath could be at its hottest.

The heat would be drawn up from the basement through the building via flues located in the walls, built of special ceramic ‘box tiles’, before venting through the roof. As a result, the floors, baths and walls of the caldarium would have been too hot to touch, and bathers wore wooden sandals to protect their feet.

Image: An artist’s reconstruction of the hot room of the baths at Chesters Roman Fort

© Historic England/English Heritage Trust (illustration by Mikko Kriek)

Public baths

Many large public bath-houses (thermae) were built in towns and cities and were some of the most spectacular buildings in the Roman Empire. Some of the most famous, like the baths of Caracalla, were bestowed by emperors as a gift to the people of Rome. During the conquest of Britain, the Romans constructed new towns to secure their rule and bring the Roman style of life to the province. All new towns were ultimately based upon Rome and had similar amenities albeit on a smaller scale.

The public baths in towns and cities, such as Wroxeter, were built at the expense of the wealthy as centrepieces to the new style of urban life. They were run on behalf of the town council and provided at a nominal fee so that all residents could afford to attend.

The baths at Wroxeter Roman City took up an entire city block and were at the heart of the community for over 200 years. Different parts of the complex had different functions. In the large hall (basilica) patrons could exercise or socialise before heading into the bathing suite next door. They could also purchase the services of medical and spiritual specialists who occupied small cubicula (booths) in the aisles, or get hair and beauty treatments.

The bathing suite itself had large rooms with high-vaulted ceilings to accommodate hundreds, possibly thousands of bathers each day in its hot and cold rooms. The suite was lavishly decorated with mosaic on the floors and walls and had a painted ceiling. Finally, a food market sold choice cuts of meat for fine dining while inns provided a dinner for those without cooking facilities at home. A meal with friends that you had met during your bath completed the Roman bathing experience.

Bathing on the Frontier

A bath-house was also a very typical site in Roman forts. Chesters Roman Fort on Hadrian’s Wall has one of the best-preserved military bath-houses in Britain. Ideally located next to the refreshing waters of the North Tyne river, the baths had a large changing hall, with niches that once held statues of the gods, and plenty of room for the sociable activities associated with bathing: gambling, socialising and exercise. Bathers then entered either a suite of warm, hot and cold rooms ending with a cold plunge pool or alternatively the dry heat of the sudatorium.

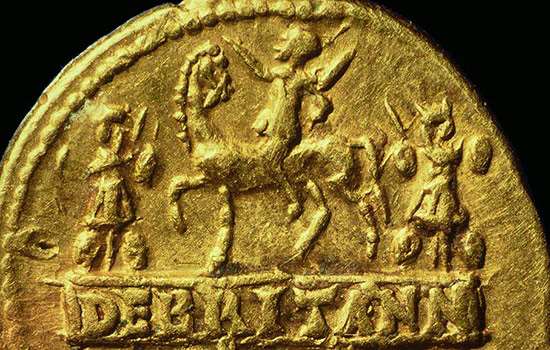

The well-equipped baths served the garrison of around 500 soldiers whose job was to patrol the frontier and protect against raiding. From the late 2nd century the garrison was the second Asturian cavalry unit. Originally raised in northern Spain, the soldiers were auxiliaries – non-Roman citizens, serving the empire for 25 years in return for the gift of citizenship. By providing such facilities, there was an expectation that the would-be citizens would adopt standard Roman cultural practices.

But forts such as Chesters were not just military communities; they were often surrounded by settlements for local populations who gravitated to the opportunities for trade. Intriguingly, like other baths associated with the forts of Hadrian’s Wall, Chesters’ baths were located outside the fort walls within the settlement, and therefore potentially available to the local population.

Private Bath Suites

A personal bathing suite was also an essential part of a Roman elite house. Lullingstone Roman Villa in Kent was one of many homes built by wealthy Romans at the centre of their country estates. Its bathing suite took up an entire wing, consisting of a warm room, two hot rooms and an unheated room with cold plunge. It was as large as some fort bath-houses.

The purpose of villas was not just to provide comfortable living, but to demonstrate the status of their owners. The owner of Lullingstone was probably a wealthy and powerful official, perhaps even the governor of Britain himself. Its dining room was used to entertain prestigious guests and featured spectacular mosaics, depicting scenes from Roman mythology. The private bath suite was essential for entertaining the select few who were welcomed into the private areas of the villa, where more intimate meetings and gatherings took place.

Finding Roman Baths

Bath-houses can often be spotted by the distinctive stone or ceramic pilae used to support the floors of the hot and warm rooms. Sometimes it is possible to spot the pinkish hue of the waterproof cement (opus signinum) used to line the walls or even the tiled surfaces of the baths, such as in the cold plunge at Richborough Roman Fort.

In addition to those discussed above, military bath-houses can be seen at Housesteads along Hadrian’s Wall, Ravenglass on the Cumbrian coast, and most spectacularly at Hardknott Fort in Cumbria, where the remains of a laconicum (circular sweating room) loom above the majestic Esk Valley.

Part of a public bath-house can be seen at Jewry Wall in Leicester, and at Wall Roman Site there once stood a bath-house provided for officials staying the night at the mansio (official hotel), while travelling on Rome’s business. A luxurious private bathing suite, including a spectacular mosaic floor featuring exotic sea creatures, is visible at Great Witcombe Villa. Together these bath-houses offer a slice of Roman bathing culture, which was central to the society of Roman Britain for over 350 years.

Header image: A reconstruction of the main bathing suite at Wroxeter in about AD 200 © Historic England/English Heritage Trust (illustration by Mikko Kriek)

Explore more on Roman Britain

-

Explore Roman Britain

Learn more about Roman daily life, politics, religion, art and commerce from our articles about Roman Britain.

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall and the people who lived there than any other site along the Wall.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads that the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

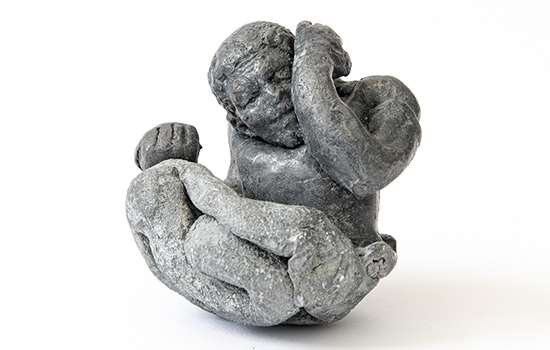

Figurine of an African warrior

Recent research into a lead figurine of a black African discovered at Wall Roman Site has led to a reinterpretation of its identity.

-

Emperor Hadrian

Emperor Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

Septimius Severus

Learn about the Roman emperor who conducted brutal military campaigns in Parthia and Britain, and left a lasting mark on Hadrian’s Wall.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.