The Romans in the Lake District

Hardknott was one of three forts joined by a road that secured Roman control of the Lake District. The Roman army had rapidly established control over the south and east of Britain after the invasion of AD 43, and from around AD 70 they advanced into northern England. However, at this stage they bypassed the Lake District, instead marching north from Chester into Scotland.

It was only after the Romans retreated in around AD 90 to a frontier between the river Tyne in the east and the Solway Firth in the west that the army pushed into Cumbria. Initially they built forts at Ambleside and Watercrook.

Emperor Hadrian overhauled the empire’s frontier strategy and completely reorganised the garrison of Roman Britain. Most dramatically, from AD 122 Hadrian’s Wall was built to control access from the north. It included a chain of installations protecting the Cumbrian coast. Early in Hadrian’s reign, forts were also built at Hardknott and Ambleside (replacing the earlier fort there), along with a small fortlet at Ravenglass on the coast. These forts controlled the route down the Esk Valley, and access to the coast and the wider road network.

Later in Hadrian’s reign the fortlet at Ravenglass was replaced by a large permanent fort. It is not entirely obvious why, but Hardknott Fort then went out of use. Perhaps the large garrisons at forts at either end of the road were more strategically useful, making Hardknott redundant. The forts at both Ambleside and Ravenglass remained thriving communities until Roman rule in Britain ended in about AD 400.

The Hardknott garrison

The only known garrison stationed at the fort was the Fourth Cohort of Dalmatians, who were originally recruited from what is now Croatia. Although little is known about the garrison, the size of the fort suggests that they were 500 strong. They would have monitored travel along the road, enforced Roman law and responded to any trouble from the local population.

The Dalmatians were auxiliaries – soldiers recruited from the large population of non-citizens living within the Roman Empire. They were usually transferred across the empire to serve. The forts at Ravenglass and Ambleside also housed auxiliaries, as did the forts of Hadrian’s Wall.

Alongside the units of citizen soldiers – known as legionaries – auxiliaries were vitally important to the Roman army. Their fighting ability complemented that of the legions. Often they had specialist skills, like archery, horsemanship or seamanship.

There were great benefits to serving in the Roman army. The pay was good, if not as high as in the legions. And if a recruit could survive the many risks of being at the sharp end of Rome’s wars, auxiliaries could achieve an honourable discharge and receive the honour and rewards of Roman citizenship.

The fort at Hardknott looking north-west, showing how its walls rise and fall following the irregular contours of the ground

The fort walls and enclosure

Most Roman forts are shaped like a playing card, but Hardknott is more of a square, presumably because of the difficult and uneven terrain. The exterior walls are the best-preserved fort walls in Britain, standing to a height of 2 metres. They were partially rebuilt in the 1950s, with a slate course marking their original height below the modern reconstruction. Unlike at many Roman forts, the stonework is rough, reflecting the hardness of the rock, which was difficult for the soldiers to shape.

The walls had four gates, one on each side, and towers at each corner. The main (south) gate, and those in the eastern and western walls, had two carriageways; the north gate had just one, presumably because of its precipitous location.

Most of the area of 1.3 hectares enclosed within the walls would have been filled with barracks for the soldiers, but little evidence of their presence survives because they were built from wood.

The central buildings

In the centre of the fort are the well-preserved remains of the fort’s three most important buildings – the granaries, headquarters building and commandant’s house.

To the east are the granaries, which contained the supplies for the garrison. They are easily identified by their distinctive buttresses, which supported the thick stone walls and heavy roof needed to keep the food cool.

Directly opposite the south gate is the principia (headquarters), where the commanding officer gave orders and conducted important religious ceremonies. Offices and the regimental records sat either side of the aedes (shrine), where the unit’s standards were kept. Normally a sunken treasury would be dug beneath the aedes, but the hard rock here meant the pay of the unit was probably kept in strongboxes.

The commanding officer lived next door in the praetorium, a large house that befitted his status as a member of the Roman elite. Typically, such a house had four ranges of rooms around a central courtyard. Only one range is visible today: perhaps the others were wooden, or the house wasn’t finished.

The parade ground

About 200 metres east of the fort, along a track that marks the route of a small Roman road, lies a military parade ground. This is one of the rarest military features to survive from Roman Britain. To create the parade ground, the garrison moved an estimated 5,000 cubic metres of stone and earth to flatten a 140 by 80 metre area. This massive investment of effort enabled the unit to practise fighting techniques to ensure they were adequately prepared for war.

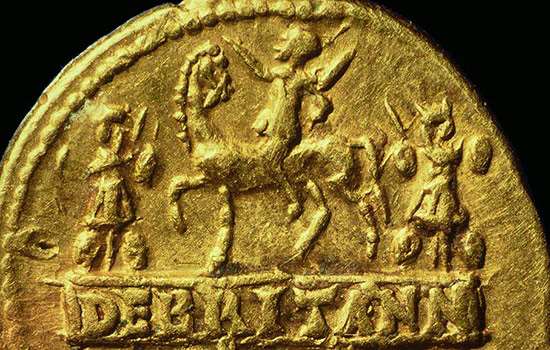

We don’t know whether the Hardknott garrison included cavalry, but the size of the parade ground suggests it may have been used to practise cavalry as well as infantry techniques. At about the time when Hardknott was occupied, the Roman author Arrian wrote the Ars Tactica (The Art of Tactics) in honour of Emperor Hadrian. It records the cavalry’s elaborate displays of horsemanship on their parade grounds. The riders were required to manoeuvre in intricate patterns and throw javelins with pinpoint accuracy into the shields of their comrades.

On the northern side of the parade ground is a man-made, wedge-shaped mound. It has been interpreted as a tribunal, the raised platform from which the commanding officer oversaw the soldiers’ manoeuvres. However, its shape and large size suggest it was more likely to have been the base of a shrine, perhaps to the Campestres, the goddesses of the parade ground.

The bath house

Just south of the fort lie the remains of its bath house. Its three main rooms were arranged in a row. Bathers proceeded from an unheated room to a warm room before finally entering a hot room, where there was probably a hot bath. They then returned to the unheated room to finish the bathing process by taking a plunge into the cold bath.

Next to the rectangular bathing suite is a circular dry hot room, or laconicum, an alternative to the wet heat of the main bathing suite. Today, it seems strangely marooned from the rest of the complex, implying bathers would have had to walk outside to reach it. However, it’s possible that the structures were once joined by a wooden changing room.

Painted plaster, discovered when the baths were excavated in the 18th and 19th centuries, demonstrates that the bath house was well decorated as well as functional. Unfortunately, during the excavations some important clues as to the baths’ function and design were removed. These include the pilae – small stacks of stones or tiles – that held up the floors of the warm and hot rooms, allowing hot air to circulate and warm the rooms above.

Roman bathing

Bathing was central to daily Roman life in a way that was quite different from bathing today. The Romans bathed together in bath houses that featured rooms heated to different temperatures and shared baths. They saw bathing as not only crucial to their health, but also an important part of what made them Roman. It was integral to the social life of the community.

The Roman bathing experience involved moving through a sequence of rooms. After undressing, bathers would progress from an unheated room (frigidarium) to a warm room (tepidarium) and then to a hot room (caldarium) before heading back to the unheated room and taking a refreshing dip in a cold plunge pool. They probably wore bathing clothes, including wooden sandals to protect their feet from the hot floors. They also carried a toilet kit that included bottles of oil and curved metal blades called strigils, for scraping oil and dirt from the skin.

Roman bath houses have been discovered across Britain, from the large public baths of towns and cities, to fort bath houses like this, and the private bathing suites of the Roman elite. The soldiers serving at Hardknott were taking part in the same quintessentially Roman practice as their fellow citizens across the empire.

Read more about Roman bathingDiscovery and significance

For centuries Hardknott’s spectacular and remote setting and state of preservation have inspired wonder at the Roman legacy in Britain.

The fort’s location was known since the time of Tudor antiquarian William Camden, who wrote about the fort in 1607. Excavations in the late 19th century explored the walls and uncovered the baths. However, much valuable archaeology was taken away by souvenir hunters.

Excavations in the 1950s, and then in the 1960s under Dorothy Charlesworth, attempted to understand what had been discovered at the bath house and central range. They found evidence of barracks in the front of the fort, but only slight and inconclusive evidence of building behind the central range.

Crucially, they discovered an inscription near the southern gate, which revealed both the name of the cohort stationed at the fort and that the fort was built during Hadrian’s reign. The excavations also found a number of fragments of leather, including several shoes, which had been preserved in peat near the granaries.

Although the fort was only used briefly, its evocative setting has ensured that Hardknott has made an outsized contribution to our imagination of Roman Britain. The poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850), who lived in the Lake District, invoked the former Roman presence at the

lone Camp on Hardknott’s height,

Whose guardians bent the knee to Jove and Mars.

Hardknott continues to inspire visitors to wonder about the Roman past to this day.

Further reading

P Bidwell, M Snape and A Croom, Hardknott Roman Fort, Cumbria, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Research Series 9 (Kendal, 1999)

D Charlesworth, ‘The granaries at Hardknott Castle’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, 63 (1963), 148–52

RG Collingwood, ‘Hardknot Castle’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, 28 (1928), 314–52

CW Dymond, ‘The Roman fort at Hardknott, known as Hardknott Castle’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, 12 (1892–3), 375–439

DCA Shotter, ‘Three Roman forts in the Lake District’, Archaeological Journal, 155 (1998), 338–51

RP Wright, ‘A Hadrianic building-inscription from Hardknott’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, 65 (1965), 169–75

Find out more

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out more about the network of forts and roads that the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Visit Hardknott Roman Fort

This remote and dramatically sited fort was founded under Hadrian's rule in the 2nd century. Well-marked remains include the headquarters building, commandant's house and bath house.

-

Listen to our audio guide

Our audio guide is designed to be enjoyed whether you are visiting Hardknott or want to listen at home or elsewhere.

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.