Recreating the theatre

Although the ground-floor room of the keep remains little altered, the theatre’s wooden stage has not survived. But using clues from prisoners’ memoirs, documents preserved by the prison governor, and a prisoner’s drawing, English Heritage has been able to recreate the stage, to give visitors an impression of what the theatre would have looked like 200 years ago.

This film tells the story of the theatre and its recreation. It includes extracts from a performance of one of the prisoners’ plays staged in the newly recreated theatre on 19 July 2017. The play, Roseliska, was performed by Past Pleasures in conjunction with the University of Warwick.

From Spain to Portchester

This remarkable story begins at the Battle of Bailén in southern Spain in July 1808, when a Spanish army, allies of the British against Napoleon, defeated a French force. The Spanish imprisoned 7,000 French captives on the tiny, deserted island of Cabrera in the Mediterranean, five miles off the coast of Majorca.

The prisoners suffered from disease and malnutrition on the island, and many of them died. Yet despite the appalling conditions, one group of prisoners passed the time by making a makeshift theatre in a cave, where they performed classic French comedies.

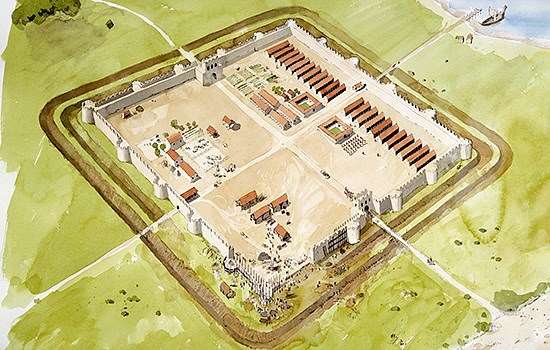

Eventually the Spanish transferred the Cabrera prisoners to their British allies, and they were moved to England. They arrived at Portchester Castle – then one of the main ‘depots’ for prisoners of war in Britain – on 20 September 1810. Almost immediately, they began to build a fully functioning theatre on the ground floor of the castle keep.

Building the theatre

Portchester’s commander, Captain William Paterson, seems to have been a kind and sympathetic man, who understood that the prisoners needed to find ways of whiling away the time. So he provided them with ‘a very large quantity of wood’, canvas and other materials, to build a stage, scenery and boxes.

The leader of the theatrical troupe was Jean François Carré, who had been a stage technician at one of the grand theatres in Paris. Probably thanks to his knowledge, the Portchester theatre was highly sophisticated. As Philippe Gille, the company’s juvenile lead, later wrote in his memoir, Monsieur Carré:

arranged a row of boxes, so that the room could hold 250 or 300 people. He ‘machined’ the theatre, in such a way that the most difficult scene-changes could be executed. Painter and decorator, as well as skilled machinist, this artist … by the magic of his talent transformed the most frightful abode in the castle into a fairy palace.

The theatrical troupe

From the prisoners’ memoirs we know that there were about 66 prisoners in the theatrical troupe. All were of course men, and some specialised in playing women’s parts. As well as the actors, there were six dancers and a 12-piece orchestra. Music was an integral part of many of the plays, and Marc-Antoine Corret, a Paris-trained horn player, composed much of the music for the performances. He returned to a professional career as a conductor in Rouen, France, after the war.

A theatre needs backstage staff too, and other prisoners – who had all been conscripted into Napoleon’s army, and came from many walks of life – brought different skills to the company. Among the prisoners listed as being part of the theatrical troupe were carpenters, a wigmaker, a florist, a lamplighter and a maintenance man.

Paris hits

Over the next three years the prisoners staged a variety of plays, from one-act comedies or ‘vaudevilles’ to three-act melodramas. At the time, melodramas – involving elaborate scenery and stage effects, fight scenes and dancing – were immensely popular on the Paris stage. With his Paris connections, Carré was sent the scripts of some of the latest hit plays, so the prisoners were performing them at Portchester very soon after they had premiered in Paris.

The prisoners wrote out other plays from memory – but they were also writing their own. Two of the troupe wrote a full-scale melodrama, Roseliska, or Love, Hate and Vengeance, taking their inspiration from one of the Paris plays. Roseliska addresses a number of themes close to the prisoners’ hearts – escaping from prison, the faithfulness of long-separated couples, and the humanity of a prison guard. The full script survives in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Theatre and Performance Collections.

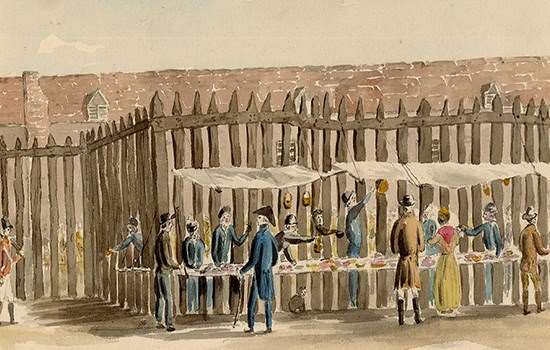

A local audience

At first, local people were allowed into the castle to watch the French prisoners’ plays. All the evidence suggests that they loved what they were seeing. A reviewer for the Hampshire Telegraph and Chronicle wrote in January 1811 that

It is no exaggeration of their merit to say, that the Pantomimes which they have brought forward, are not excelled by those performed in London.

Not everyone was so delighted with the theatre’s success, however. The proprietor of the main theatre in Portsmouth complained – probably because he was suffering from the competition – and the government ordered the theatre to be closed. But Captain Paterson, realising how much the theatre meant to his prisoners, persuaded the Admiralty to reconsider. After a few months it reopened, although now on condition that only the prisoners and garrison would be allowed to watch the plays.

The prisoners in the troupe warmly appreciated Captain Paterson’s support. They sent him personal invitations to the premières of every one of their performances, and even presented a tableau in which they adorned a bust of him with a laurel wreath – an expression of gratitude for his support.

A unique story

Many aspects of this story may seem startling today – perhaps most of all, the fact that British audiences were watching French prisoners performing French plays, at a time when hostilities between Britain and France were at their height. In many ways, attitudes to prisoners of war at the time seem to have been surprisingly humane. We know that French prisoners took part in theatricals elsewhere in Britain, particularly the officers, who were allowed to live on parole among the local community. But the existence of a French prisoners’ theatre of this scale and complexity in Britain is unique.

In 1814 the war ended, and the prisoners returned to their old lives in France. The theatre was dismantled, and for a long time after they left, their story was a forgotten chapter in the castle’s history. Like the history of black prisoners of war ten years earlier, it is now being brought back to life at Portchester Castle.

Find out more

-

Prisoners of war at Portchester Castle

During the wars with France between 1793 and 1814, thousands of prisoners of war were held at Portchester Castle. Where did they come from, and what was life like at the castle?

-

Black prisoners at Portchester Castle

Read the extraordinary story of a group of over 2,500 prisoners of war who were brought to Portchester Castle in 1796 from the Caribbean island of St Lucia.

-

History of Portchester Castle

Read a full history of the castle, from its origins as a Roman fort, through its development as a medieval castle and its role as a prison, to the present day.

-

French theatre in the Napoleonic era

Find out about Warwick University’s research into French theatre in the Napoleonic era, and the research behind the performance of Roseliska in July 2017.