Early life

Henrietta Howard was born in 1689 into a titled and respected family, the Hobarts of Blickling Hall in Norfolk. However, her early life was far from easy. By the time she was 12 she had lost her father in a duel and her mother to illness, and the family was burdened with mounting debts. Whether in the hope of finding security, or perhaps through genuine affection, in 1706 she married Charles Howard, the youngest son of the 5th Earl of Suffolk. Their only child, Henry, was born the following year.

The marriage was a disaster: as Henrietta’s friend the 4th Earl of Chesterfield later observed, ‘Thus they loved, thus they married, and thus they hated each other for the rest of their lives.’ Charles was described as ‘wrong-headed, ill-tempered, obstinate, drunken, extravagant, brutal’, and soon squandered what money the couple had. As they moved from lodging to increasingly poorer lodging, hiding from creditors, Henrietta was frequently left hungry and lived in fear of her abusive husband. These were, she later wrote, ‘circumstances of horror’.

Yet Henrietta refused to accept her dire circumstances. She raised funds to travel with Charles to Hanover in Germany. There, she hoped to curry favour with the ruling family, who would inherit the throne of Great Britain upon the death of the reigning monarch, Queen Anne.

Dual roles

Henrietta’s plan was successful: on the accession of the Elector of Hanover as George I of Great Britain in August 1714, she was made a woman of the bedchamber to his daughter-in-law, Caroline, Princess of Wales. Charles Howard became a groom of the bedchamber to the king.

Soon after Henrietta’s return to England, she also became mistress to Princess Caroline’s husband, the Prince of Wales (later George II). The role of mistress was an established one in the royal courts of Europe: far from being secretive, it was a semi-official position which added to the image of royal power and authority. As the courtier John Hervey wrote, the Prince of Wales’s attachment to Henrietta was that of a man who saw a mistress as a ‘necessary appurtenance to his grandeur’. The politician and writer Horace Walpole later described the prince’s desire to create an image of ‘gallantry’ and to show that he was not ‘governed’ by his wife.

Henrietta’s dual roles of mistress to the prince and servant to the princess were not always easy to reconcile, requiring great tact and diplomacy. However, her roles at Court offered the hope of a better life.

Life at court

With joint lodgings at St James’s Palace, Henrietta and Charles now had a roof over their heads as well as an income. When the king and prince fell out in 1717 and the prince left to set up a rival court at Leicester House, Henrietta moved to lodgings there while Charles remained at the king’s court. Living apart from her husband was something Henrietta had no doubt longed for, although it also meant an unwelcome separation from her son, who remained with his father.

During her time at Court Henrietta began to gather an important cultural and political circle around her. Described by contemporaries as ‘handsome and witty’, ‘always ready to do a good turn’ and with ‘a good head and good heart’, she befriended notable politicians, courtiers and writers, among them Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and John Gay. Her role as king’s mistress gave her a degree of power, and although this was perhaps less than some who courted her supposed, she had ‘just influence enough’, as Lord Hervey caustically observed, ‘by watching her opportunities, to distress those sometimes to whom she wished ill’.

Henrietta was also noted for her discretion and keeping her thoughts and feelings close to her chest, creating a distance which was perhaps necessary in a Court full of gossip. Her diplomatic nature earned her the nickname ‘the Swiss’ and her rooms at Court the ‘Swiss Cantons’.

Hearing loss

Despite Henrietta’s masterful navigation of Court life, from her late twenties or early thirties she suffered from hearing loss. In his poem ‘A Certain Lady at Court’, Alexander Pope wrote with deliberate ambiguity of her refusal to accept compliments: ‘When all the world conspires to praise her, / The woman’s deaf, and does not hear.’

The cause of Henrietta’s hearing loss is unknown, but there is evidence that she sought to improve her hearing. In about 1728 she consulted the surgeon to Queen Caroline, Dr Cheselden, who operated (unsuccessfully) on her ‘jaw’ (possibly her eardrum). The pain from this was, she wrote, ‘almost insupportable and the Consequence was many weeks of misery’. Henrietta also tried using a hearing aid. In her later years she was said to have used a tortoiseshell hearing trumpet when reminiscing with Horace Walpole, who wrote: ‘She was extremely deaf, and consequently had more satisfaction in narrating than in listening.’

Henrietta was not the only member of her social circle to experience deafness. In 1727 Jonathan Swift wrote to Henrietta of his ‘bad head and deaf ears’. Henrietta’s friend Lord Chesterfield often lamented the isolation he felt due to hearing loss in his later years, and George II and Princess Caroline’s second daughter, Princess Amelia, was described as ‘more than a little deaf’.

Image: Henrietta was said to have used a hearing trumpet to amplify sounds. This engraving from Exercitationes Practicæ circa Medendi Methodum by the Dutch physician Frederik Dekkers (1694) shows the kinds of aids, including hearing trumpets, which might have been available to her

A royal gift

In 1723, the Prince of Wales presented Henrietta with a gift. This included gilt plate, jewels such as a ‘diamond ring’ and ‘ruby cross’, gold watches, and all the chinaware, plate, linen and furnishings from her lodgings at Court. But more substantially, it also included investments in the South Sea Company and Bank of England amounting to £11,500 – equivalent to almost 40 times her salary. Many of the shares in companies such as the South Sea Company, which traded in enslaved people, were owned by the royal family and members of the aristocracy. Henrietta already held shares in several companies and would continue to invest throughout her life.

Crucially, the prince stipulated that he was making the gift with the intention that ‘some provision and way of Living may be made for the said Henrietta Howard’ free from any interference from her husband. It was to be hers alone (usually a woman’s property became that of her husband on marriage), as was any income gained if she chose to sell it, or any ‘premisses’ she might buy with the proceeds.

We don’t know whether Henrietta sold any part of the gift, but it gave her financial and personal independence from her husband, enabling her to set up a home of her own. The following year, construction began on her new home, Marble Hill.

Building Marble Hill

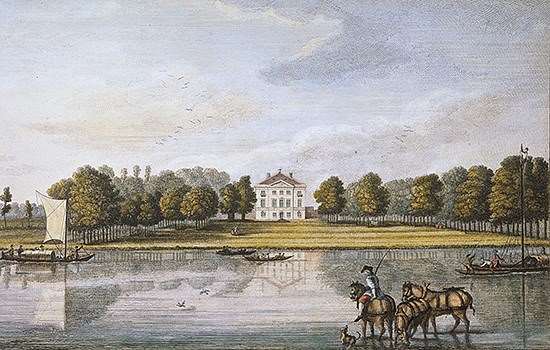

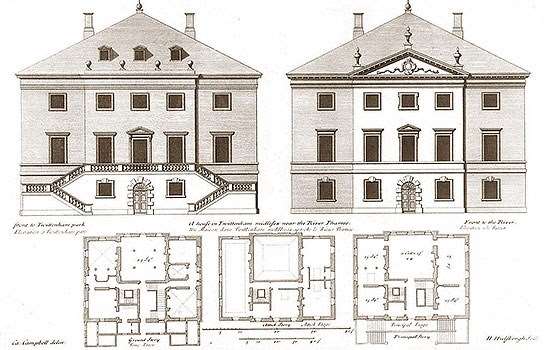

Henrietta built a villa on the banks of the Thames in Richmond, an area rich with cultural, political and royal connections. Marble Hill was a textbook example of Palladian architecture, the increasingly fashionable building style inspired by the Italian architect Palladio (1508–80) and based on classical principles. To accompany her house, she created a garden inspired by those of ancient Greece and Rome.

Henrietta drew upon the network of friends and acquaintances she had cultivated throughout her life to help build her home. The ‘Architect Earl’ – Henry Lord Herbert, 9th Earl of Pembroke – and the builder of Marble Hill, Roger Morris, may have contributed to the design of the house, while the professional gardener Charles Bridgeman and Henrietta’s neighbour Alexander Pope played leading roles in the garden design.

Henrietta also seems to have been knowledgeable about architecture and design herself. As any patron might, she looked over plans for her home and contributed to discussions on the garden. Once construction was under way, Mary Campbell, a favourite of the prince’s at Court before her marriage, wrote to Henrietta that though she longed to hear from her, she was no doubt ‘up to the ears in bricks and mortar; & talks of freeze and cornice’. She also hoped to improve herself ‘in the forms of art, in order to keep pace with you [Henrietta]… otherwise I know I shall make but a scurvy figure in your room’.

Leaving court

Marble Hill offered Henrietta the prospect of rural retreat from the tensions and strains of Court life as well as from her abusive husband. However, it was another 20 years after construction began before Henrietta left the royal household, and Charles, as ever, continued to harass her for money.

In 1728, King George II (the prince had ascended to the throne in 1727) increased Henrietta’s allowance so she could pay off Charles with a yearly sum in return for signing a deed of separation. Separating from Charles was a bold step, unusual for the time, and ran the risk of censure and scandal. But unlike a divorce, a deed of separation was made outside the courts and was used by high-status couples to avoid public scrutiny.

In 1731, following her brother-in-law’s death, Henrietta became Countess of Suffolk, and to reflect her new rank she was elevated from the position of woman of the bedchamber to mistress of the robes to Queen Caroline. This was a far less arduous role, which also gave her more freedom to enjoy her new home. She wrote to her friend John Gay, ‘every thing as yet promises more happiness for the latter part of my life than I have yet had a prospect of … I shall now often visit Marble Hill: my time is become very much my own.’

Two years later Charles died and in 1734 Henrietta finally left Court, as she had longed to do for many years.

Life at Marble Hill

After leaving Court, Henrietta took a second chance on marriage. In 1735 she married the politician George Berkeley, or as she called him in one letter, ‘My Life! My soul! My joy!’.

Their correspondence reveals a loving and caring relationship that could not have been more different from Henrietta’s first marriage. Of their life at Marble Hill, Henrietta wrote: ‘We live very innocently, and very regular, both new scenes of life to me.’ They visited friends, took a trip to the continent and hosted guests.

Marble Hill became a centre for Henrietta’s influential cultural, intellectual and political circle. Contrary to the expectations of some – including the queen – that her social network would not survive her removal from Court and consequent loss of influence, she entertained friends here on a scale which was said to rival the royal court. As Pope wrote in 1735: ‘There is a greater court now at Marble-hill than at Kensington, and God knows when it will end.’

As well as maintaining friendships from life at Court, Henrietta forged new ones, for example with Horace Walpole, who came to live nearby in 1747.

Henrietta’s son had died in 1745, but at Marble Hill she and George gave a home to Henrietta’s niece and nephew, John and Dorothy Hobart. Henrietta and George’s letters to each other often mention their young dependants. On one occasion George wrote to Henrietta that she should be firmer with Dorothy ‘for Miss Hobart’s sake begin your office of Rebuker with her’. After 11 happy years of marriage, George died in 1746.

In 1763 Henrietta welcomed a new companion to her home, her great-niece Henrietta Hotham. The pair appear to have formed a close bond and Henrietta Hotham sometimes wrote on Henrietta’s behalf to update her friends when she was unwell.

After seemingly recovering from one bout of ill-health, Henrietta died in the bedchamber of her beloved Marble Hill on 26 July 1767.

Henrietta Howard navigated the many challenges of her life – her early misfortunes, a disastrous first marriage, her role as both king’s mistress and queen’s servant, and hearing loss – with tenacity, intelligence and resourcefulness. Marble Hill not only embodies her legacy as a patron of architecture and landscape gardening, but also stands as testament to a woman who fought hard for her independence and security.

By Megan Leyland, Senior Properties Historian, English Heritage

Related Content

-

Visit Marble Hill

See how we’ve transformed Marble Hill by restoring the lost gardens that Henrietta created, and told her story with new displays in the house.

-

History of Marble Hill

Read a full history of this English Palladian villa and its gardens beside the Thames, from its origins in the 1720s as a retreat from court life for Henrietta Howard to the present day.

-

Marble Hill Collection Highlights

Explore some of the key items from the collection at Marble Hill, which reveal Henrietta Howard’s taste and status.

-

Women in history

Read about some of the women who left their mark on society and shaped our way of life – from fearless monarchs to pioneering scientists.

Further reading

Tracy Borman, King’s Mistress, Queen’s Servant: The Life and Times of Henrietta Howard (London, 2010)

Julius Bryant, Mrs Howard: A Woman of Reason (London, 1988)

JW Croker (ed), Letters to and from Henrietta, Countess of Suffolk and her second husband, the Hon. George Berkeley from 1712 to 1767, vol 1 and vol 2 (London, 1824) (accessed 26 Oct 2013)

Lord Hervey, Lord Hervey’s Memoirs, ed Romney Sedgwick (London, 1952)

WS Lewis, The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence (London, 1937–8) (accessed 26 Oct 2023)

Lewis Melville, Lady Suffolk and Her Circle (London: Boston and New York, 1924)

The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield Including Numerous Letters Now First Published from the Original Manuscripts, vol 2 (London, 1845) (accessed 26 Oct 2023)

AMW Stirling, The Hothams: Being the Chronicles of the Hothams of Scorborough and South Dalton from their hitherto unpublished family papers (London, 1918) (accessed 30 Oct 2023)

Horace Walpole, Reminiscences: written in 1788 for the amusement of Miss Mary and Miss Agnes (London, 1819) (accessed 26 Oct 2023)