Medieval: Warfare

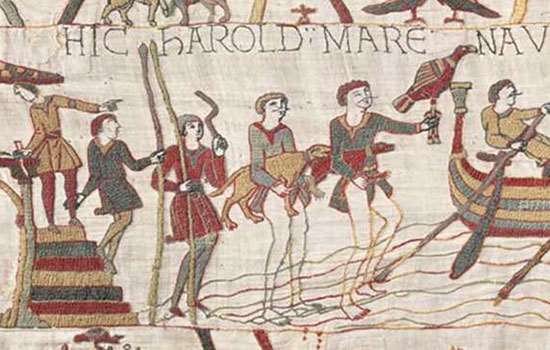

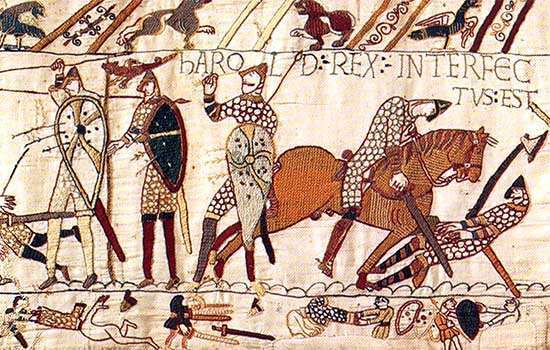

The Norman Conquest was achieved largely thanks to two instruments of war previously unknown in England: the mounted, armoured knight, and the castle. The former was a key factor in William the Conqueror’s triumph at Hastings, while the latter dramatically militarised the English landscape.

Later in the medieval period, England was fighting the series of conflicts with France later known as the Hundred Years War (1337–1453). In England itself the Wars of the Roses (1455–85), fought for possession of the Crown, were marked by exceptionally bloody conflicts, such as the Battle of Towton.

Norman knights

Fighting on foot, the English army at the Battle of Hastings could not withstand the charges of the mounted Norman knights, who were protected by long chainmail hauberks (tunics) and armed with spears.

Substantial wooden saddles, well-designed stirrups and the use of lances secured firmly beneath the armpit gave the Norman knight a firmer seat on his horse, and thus impressive striking force. A knight’s armour and heavy horse were expensive to buy and maintain, though. So the king, in return for ‘knight service’, granted land as an incentive.

The first castles

An intensive programme of fortress building controlled the newly conquered land.

The Normans’ first castles were ditched and banked earthwork enclosures (the bailey), defended by wooden stockades and often including a mound (or motte), a strongpoint with its own ditch and stockade. Earthwork motte and bailey castles were quickly and easily constructed – local forced labour helped. Well over 500 were raised in the 20 years after 1066.

In castles such as Eynsford, Kent, the timber stockades of the bailey were soon replaced with stone ‘curtain’ walls. Those of the motte were replaced with circular stone-walled ‘shell keeps’.

Castle keeps

Keeps – also known as great towers – were the chief strongpoints of most early castles, and may also have been where the owner or his representative resided. Small stone keeps could be built on the top of mounds, but larger keeps required firmer foundations. At the Tower of London, these were built at ground level from the outset.

The rectangular keeps of Middleham and Scarborough in North Yorkshire and Dover in Kent were all raised during the reign of the greatest of all royal castle-builders, Henry II. But their corners were vulnerable to undermining during sieges, as happened at Rochester Castle, Kent, in 1215.

Other forms of keep therefore began to appear at the end of the 12th century: polygonal at Orford Castle, Suffolk; cylindrical with wedge-shaped buttresses at Conisbrough Castle, South Yorkshire; and round, as at Longtown Castle, Herefordshire.

Concentric castles

Castle design was changing, with a new emphasis on multi-towered enclosing walls and strong gatehouses instead of keeps. Framlingham Castle, Suffolk, among the first built in the new style, has 13 towers studding its walls, but no keep at all.

By about 1250 Dover Castle had both inner and outer circuits of towered walls around its existing keep, each line of defence supporting the others. This made Dover the first ‘concentric’ fortress in western Europe.

The same concentric principle – reinforced by powerful gatehouses effectively acting as keeps – was used for the chain of castles (including Harlech and Beaumaris) that Edward I built between 1277 and 1294 to control newly conquered north Wales. These represent the high point of castle building in medieval Britain.

Two wars

Following glorious runs of victories under Edward III, his son the Black Prince and the all-conquering but short-lived Henry V, the long-running conflict with France later known as the Hundred Years War eventually ended in total defeat for the English.

It had been fought almost entirely on French soil. Apart from the occasionally raid on the south coast, England suffered little direct war damage. Instead, many Englishmen profited greatly from ransoms and plunder, the proceeds of which helped pay for the building of castles such as Farleigh Hungerford, Somerset.

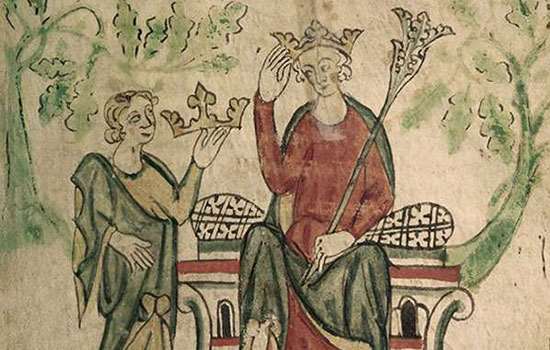

The final English defeats of the Hundred Years War coincided with an increasing breakdown of order in England. This culminated in open warfare between rival aristocratic factions striving to control the weak Henry VI and his realm.

Actual fighting between the ‘red rose’ Lancastrians and the ‘white rose’ Yorkists occupied only an aggregate of five months between 1455 and 1485, but during this civil war the English Crown changed hands six times.

Crossbows and longbows

Mounted knights, equipped with increasingly sophisticated armour, still dominated the battlefields of the Plantagenet kings’ wars with their barons, and against the Scots. Their infantry support was generally provided by spearmen and crossbowmen.

Crossbows were powerful but shot slowly, and their most experienced users were often foreign mercenaries. But at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298, Edward I’s defeat of William Wallace’s Scots army was mainly accomplished thanks to a newly popular weapon, the longbow.

The longbow was the most decisive weapon in both the Hundred Years War and the Wars of the Roses. Ideally made of a single bough of yew, ‘war bows’ had a range of well over 200 metres. At shorter ranges their needle-pointed arrows could pierce armour.

Their precise origin is uncertain. Bows had been used since prehistoric times, and Norman archers played an important part in the Battle of Hastings. But longbows of this formidable power were first recorded much later, towards the end of the 12th century.

The greatest triumph of the longbow was at the Battle of Agincourt (1415). The archers who made up five-sixths of Henry V’s army were chiefly responsible for French casualties of 10,000, compared to a few hundred on the English side.

Bitter fighting

The disproportionate number of casualties at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 seemed exceptional at the time, but late medieval conflicts were often savage. At the Yorkist victory at Towton, North Yorkshire (1461), possibly the bloodiest battle ever fought in England, total fatalities have been estimated at 28,000.

The most bitter hand-to-hand fighting was done by ‘men-at-arms’. These were nobles and gentry, often wearing suits of elaborate plate armour, and their retainers, who wore quilted ‘jacks’ and helmets. English armies rode to battle but nearly always fought on foot. Agincourt had confirmed that cavalry charges against archers were disastrous.

Cannon and castles

Although hand-held firearms were still in their infancy, cannon had begun to play an important part in sieges. Henry V used them against French fortresses and Edward IV’s heavy guns quickly reduced Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland in 1464.

But early cannon were unwieldy and difficult to transport, and were therefore more useful in static positions within castles. By the late 14th century, the gatehouse at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight gatehouse already had gunports for artillery, and in 1398–9 one of the earliest English blockhouses specifically designed for cannon, the Cow Tower, was added to the town defences of Norwich.

Gunports became virtually standard additions to 15th-century castles and even fortified manor houses such as Baconsthorpe Castle, Norfolk.

Medieval stories

-

What Happened at the Battle of Hastings?

In the early morning of 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Find out what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

Piers Gaveston and the Downfall of Edward II

Discover how Edward II’s reliance on his ‘favourites’ and possible lovers led to his abdication and death.

-

The Massacre of the Jews at Clifford's Tower

One of the worst anti-Semitic massacres of the Middle Ages took place in York in 1190. The city’s entire Jewish community was trapped by an angry mob inside the tower of York Castle.

-

Lord Hastings, Richard III and an Unfinished Castle

How William Lord Hastings’s ultra-fashionable castle at Kirby Muxloe, Leicestershire, was left incomplete following his summary and shocking execution by the future Richard III.

-

Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Why did Richard, Earl of Cornwall and one of the richest men in Europe, swap three castles for a rock?

-

Where Did the Battle of Hastings Happen?

Historians have long accepted that Battle Abbey was built ‘on the very spot’ where William the Conqueror defeated King Harold. Is there any truth in claims that the battle took place elsewhere?

-

The Misbehaving Monks of Hailes Abbey

Visitation records from abbots who came to inspect Hailes Abbey offer tantalising glimpses into the lives of the monks who lived there and the vices that may have tempted them.

-

A Canterbury Tale: The Bayeux Tapestry and St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine’s Abbey has long been celebrated for its contribution to English Christianity. But could it also be the birthplace of one of the most famous artefacts in history?

More about medieval England

-

Medieval: Architecture

For more than a century after the Battle of Hastings, all substantial stone buildings in England were built in the Romanesque style, known in the British Isles as Norman. It was superseded from the later 12th century by a new style – the Gothic.

-

Medieval: Religion

The Church was a pervasive force in people’s lives, with the power and influence of the Catholic Church – then the only Church in western Europe – reaching its zenith in England in the Middle Ages.

-

Medieval: Warfare

The Norman Conquest was achieved largely thanks to two instruments of war previously unknown in England: the mounted, armoured knight, and the castle.