Early life and ascent to power

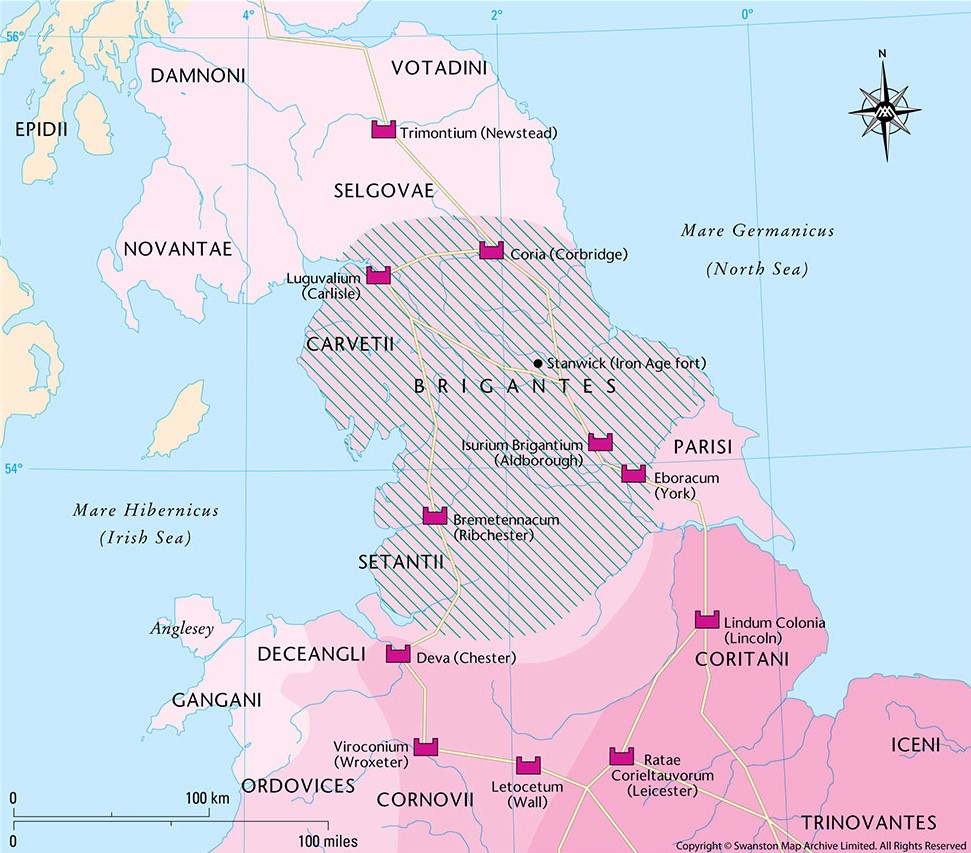

Cartimandua’s early life and how she became queen of the Brigantes are not recorded. But the evidence suggests that she was from the ruling family and either came to be leader before the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43 or gained power in the aftermath. At the time of the invasion, the British Isles were inhabited by independent tribal groups, each with a distinct culture and varying policies towards Rome. In contrast to some of the tribes who resisted the Roman conquest and were subsequently crushed by the Roman army, Cartimandua allied with Rome.

The exact nature of the alliance is unknown, but arranging for friendly ‘client’ rulers to keep control of lands on the margins of the empire was a typical Roman strategy. Rome could benefit from trade and protect the frontiers of its empire without the need to directly occupy a territory. In return, the client could expect to benefit from Roman wealth, trade and, if necessary, military aid. Cartimandua secured her position as one of the most significant rulers in Britain and a key ally of the Romans, a relationship that proved to be beneficial for both parties.

The capture of Caratacus

The invading Roman army had quickly established firm control over southern and eastern Britain, accepting the surrender of some 11 tribal groups and defeating others in battle. But Caratacus, the son of the king Cunobelinus of the Catuvellauni tribe, fled to what is now Wales after their defeat, where he continued to resist Roman rule for nine years. While leading a coalition of two tribes there, the Silures and Ordovices, he was finally defeated by the Roman governor Publius Ostorius Scapula in AD 51.

According to the Roman author Tacitus, Caratacus left his family in the clutches of the Romans and escaped to Brigantian territory. Cartimandua handed him over and he was taken to Rome, where he was paraded in public by the Emperor Claudius. Cartimandua had presented Rome with a great prize in Caratacus, helping to secure its fledgling province by ending the long war against a bitter and dangerous enemy. As a result, Tacitus says, she gained great wealth and prosperity.

Cartimandua’s capital?

Archaeological evidence suggests that a good relationship with Rome led to the growth of Brigantian power. During the rule of Cartimandua, the Iron Age settlement of Stanwick in what is now North Yorkshire grew to loosely occupy an area of 1.2 square miles. Roman goods, such as wine amphorae, rare tableware and glass, flooded into Stanwick, showing a close connection and favour with the empire. Neighbouring settlements, such as Scotch Corner, also benefited from the influx of Roman goods and produced raw materials for manufacturing.

Stanwick was not densely occupied, and while its walls were an impressive 5 metres high in places, they were ultimately limited for defence against a disciplined army. Rather than a stronghold or permanent town, Stanwick was probably used for important gatherings. Without historical evidence or an inscription bearing Cartimandua’s name, we cannot be certain of the connection with her, but it is possible that Stanwick was her ‘capital’ – its walls and material wealth intended to show off the power of its ruler and the Brigantes’ successful alliance with Rome.

Image: Excavated remains of the Iron Age rampart at Stanwick, North Yorkshire

Venutius and later rule

The Romans would later return the favour to Cartimandua when her alliance with Rome faced resistance from within the Brigantes. In AD 57, her consort Venutius led an anti-Roman faction against her and attempted to seize power. Tacitus states that this erupted when she divorced Venutius, but it also seems likely that the internal politics of the Brigantes led to differing views on policy, leadership and the Roman alliance. During the subsequent fighting, Cartimandua seized Venutius’s brother and other family members, provoking a major attack by his warriors. But the Roman provincial governor Publius Ostorius Scapula sent a legion to preserve Cartimandua’s rule.

For the next decade or so, there was peace in Brigantia. But in AD 69, Venutius again attempted to seize power. According to Tacitus, he was seemingly goaded by Cartimandua’s marriage to his former armour-bearer, Vellocatus, and sought to exploit the tumultuous civil war in the Roman Empire that had followed the death of the Emperor Nero. Without the legions that had been drawn into the Roman civil conflict, the provincial governor could only send auxiliary soldiers. These were enough to rescue Cartimandua, but insufficient to prevent Venutius from replacing her as ruler of the Brigantes. What happened to Cartimandua is unknown.

Legacy

The historical and archaeological evidence suggests that Venutius’s reign was probably short. In AD 71–4, the Roman governor Quintus Petillius Cerealis conquered the Brigantes and placed them under direct rule. Stanwick went out of use, and the Roman city of Aldborough was founded as the official administrative centre. A process of Romanisation began in the region, with the introduction of Roman material culture and urban living, a few miles from the watchful eye of a Roman legion stationed at York.

Like her contemporary, Boudicca, who led the Iceni people in revolt against Rome in AD 60, Cartimandua’s life is only recorded in the words of the Romans. Her reputation is also coloured by the prejudices the Roman author Tacitus held against powerful women. According to his account, Cartimandua was motivated by lust and was rejected as a ruler by her people due to her gender. Yet female rulers were clearly accepted and successful in Iron Age Britain.

Similarly, Tacitus calls Cartimandua treacherous for her role in capturing and handing over Caratacus to the Romans. But the matter was far from a straightforward test of loyalty. Some leaders, like Cartimandua, clearly felt Rome could be a useful friend, while others, like Venutius, perhaps felt a common bond with other British tribes against an external enemy.

Boudicca has been celebrated in modern British culture as a ‘warrior queen’ who resisted Roman tyranny, but Cartimandua was arguably a more powerful and successful figure. For more than two decades she successfully negotiated the political maelstrom created by the Roman invasion, and used her relationship with a powerful state to maintain her position.

By Andrew Roberts, Properties Historian

Header image: A Brigantian theatrical mask found near Catterick. © York Museums Trust (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Further Reading

D Braund, ‘Observations on Cartimandua’, Britannia, 15 (1984), 1–6 (subscription required: accessed 3 Feb 2021)

N Howarth, Cartimandua: Queen of the Brigantes (Stroud, 2008)

K Krakowka, ‘Cartimandua’s Capital?’, Current Archaeology (1 March 2017) (accessed 3 Feb 2021)

IA Richmond, ‘Queen Cartimandua’, The Journal of Roman Studies, 44 (1954), 43–52 (subscription required: accessed 3 Feb 2021)

Explore More

-

Women in History

Read more about the women that shaped the course of English history, from great queens, writers and scientists, to those that broke the mould or remain largely unnamed.

-

Why Women Disappeared from History

Women occupy just 0.5% of recorded history, and are often stereotyped. Bettany Hughes explores why women were written out of history.

-

Groundbreaking Female Archaeologists

Read about some of the female archaeologists who worked on sites now cared for by English Heritage.

-

Roman Britain

Read this introduction to Roman Britain, from the beginning of the invasion in AD 43 to the end of Roman rule by AD 410.