Iron Age hillfort, Roman lighthouse, Anglo-Saxon church

The origin of settlement on Castle Hill, where Dover Castle stands, may be in the pre-Roman Iron Age. The irregular shape and massive enclosed area of the castle earthworks are not typically medieval, more closely resembling a hillfort. In southern England, hillforts were built from about 500 BC until the Roman invasion, variously as places of permanent habitation or of refuge. Slight evidence of occupation in the 1st century BC was found during excavations in 1962, near the castle church of St Mary in Castro.

Seventy years after the Roman invasion in AD 43, construction of a fort began at the mouth of the river Dour. This was Dubris, a fort for the classis Britannica, a Roman fleet that patrolled the eastern Channel. Though building stopped suddenly, it began again around AD 130 and the fort was completed.

The Romans built an octagonal tower-like lighthouse (pharos) on Castle Hill around the same time, with another on the opposite hill, the Western Heights. These lighthouses supported fire beacons to act as navigation lights for ships approaching the narrow river mouth, enabling them to find a quayside outside the fort.

The fort at Dubris was demolished around AD 215 and a new one constructed around AD 270, which may have continued in use, along with the lighthouses, into the 5th century. The pharos was later reused for the church of St Mary in Castro as a chapel and bell tower, and can still be seen.

The church of St Mary in Castro dates to around AD 1000. Its exceptional size hints that it might have had a royal patron – Godwin, Earl of Wessex (reigned 1020–53), father of King Harold (r.1066), is one possibility. A cemetery discovered during archaeological excavations in 1962 indicated that a community lived nearby, perhaps in a fortified burh.

The great medieval castle

In 1066, William the Conqueror came to Dover after the Battle of Hastings to capture the port. He established a fortification, possibly around the church, but there are no surviving remains. The castle was extended in the 12th century, although we know nothing of its appearance before the great rebuilding of the 1180s.

The castle visible today was established by Henry II (r.1154–89), in the decade 1179–89. He spent lavishly, creating at Dover the most advanced castle design in Europe. His engineer, Maurice, built the inner bailey and towers, part of the outer bailey and a huge centrepiece – the immense great tower, a sophisticated building that combined defence with a palatial residence.

One important reason for this rebuilding may have been the new pilgrimage route to Thomas Becket’s shrine in Canterbury. With no substantial properties in Kent, Henry needed a magnificent and impressive setting in which to receive and accommodate important visitors making the journey.

Siege

In 1204, King John (r.1199–1216) lost the Duchy of Normandy to the French king, Philip II (r.1180–1223), resulting in enemy territory just across the Channel. This prompted more expenditure at Dover, furthering the design of Henry II in the outer wall and towers, and royal accommodation in the inner bailey.

This was the castle that resisted determined sieges in 1216 and 1217 during the First Barons’ War (1215–17), when King John fought against a coalition of English barons and Prince Louis, heir to the French throne. The castle garrison, led by Hubert de Burgh, repulsed all attempts to take the castle, though the barbican and main gate at the northern end were severely damaged.

When war ended in 1217, building resumed for Henry III (r.1216–72). The vulnerable north gate was blocked solid and replaced by two more: the main one at Constable’s Gate on the west side, also a residence for the castle constable, and a secondary one, Fitzwilliam Gate, on the east.

Read more on the Sieges of DoverThe builders remade the barbican and cut a tunnel under the outer wall to reach it, via the new St John’s Tower that dominated the outer ditch, and a covered passage across it. The passage continued as a tunnel under the Spur, where it divided into three, allowing defenders to defend the barbican.

Building continued sporadically under Henry III into the middle of the 13th century. By this time the castle had reached a peak of development, as one of the largest and most sophisticated castles in Europe. It included a royal residential complex lining the walls of the inner bailey.

In 1265 the castle was besieged again, with Eleanor de Montfort in residence. After the death of her husband at the Battle of Evesham during the Second Barons’ War (1264–7), there was a short siege at Dover, ended by negotiation with Eleanor and her nephew, the Lord Edward (son of Henry III).

From the 1260s the constable of the castle was also Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a royal officer charged with oversight of the semi-independent Cinque Ports, to ensure their service to the Crown. This is one factor which ensured that Dover remained of importance in the medieval period.

The late medieval and Tudor castle, and Stuart decline

We have only scant knowledge of the castle in the later Middle Ages, until the reign of Edward IV (r.1461–83), when the great tower was remodelled as an occasional residence. This reflected Dover’s location on the route to Flanders, which was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy, an important ally.

Dover remained important under the Tudors, especially after Henry VIII (r.1509–47) built artillery forts in Dover and along the south-east coast in 1539–40. The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, came to the castle in 1522 and met Henry there, at the start of a six-week diplomatic visit. The great tower’s royal apartments were refurbished to receive Anne of Cleves on her way to marry Henry in 1539. Elizabeth I (r.1557–1603) visited in 1573 and ensured the castle was kept in good repair during the war with Spain in the final two decades of the century.

Royalty last used the castle in 1625, when the great tower received a makeover for the French princess Henrietta Maria, on her way to marry Charles I. Thereafter the king’s favourite, the Duke of Buckingham, made alterations in the great tower and to some buildings in the inner bailey.

Afterwards the castle was neglected, playing no significant role during the Civil Wars of 1642–5. The great tower was used as a prison for French and Spanish prisoners during the Nine Years War (1688–97) and the War of Spanish Succession (1701–14), and their graffiti can be seen on its walls.

Georgian revival

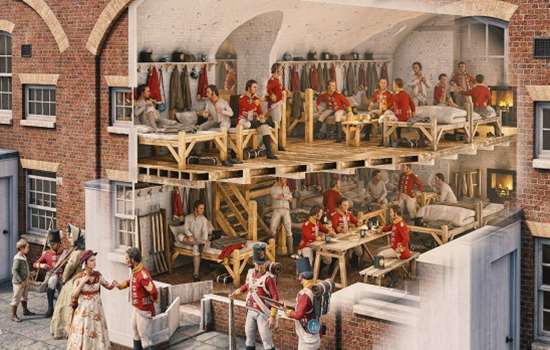

The 1740s marked a new beginning, as Britain emerged as a world power and came into conflict with its rival, France. In 1744–5, a failed French invasion and a Jacobite uprising prompted improvements to the nation’s defences. Works to the decaying buildings created a barracks in the inner bailey and great tower, and new barracks were erected in 1756–7 on Palace Green. The combined barracks accommodated 800 infantrymen, an unusually large concentration for the time, indicating the importance of Dover.

Simultaneously, military engineers recognised the weakness of the Spur as being vulnerable to bombardment by cannon from higher ground to the north-east. The barbican was remodelled as an infantry strongpoint, while the outer wall of the castle on the north-east side was reduced in height and backed by an earthwork to help absorb incoming cannon shot. Two new positions for defending cannon were built, at Bell Battery and Four Gun Battery.

The greatest modifications to the castle since Henry II occurred during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1802 and 1803–15), concentrated mainly in 1794–9. The military engineers Major William Twiss and Captain William Ford comprehensively altered the defences, most dramatically where the entire eastern outer wall was cut down and backed by an earth rampart for cannon. The outer ditch there was enlarged and lined in near-vertical brick walls.

Three huge earthwork bastions projected from these new defences, mounting cannon to fire along the eastern flanks, and served by tunnels from the castle interior. The engineers also modernised the Spur to allow a staged defence back across the inner ditch through St John’s Tower and via the medieval tunnel to the outer bailey.

The new works included underground barracks in casemates at the southern end of the castle (the Cliff Casemates) and above ground at the Spur Casemates. A new entrance was made at Canon’s Gate on the south-west and two earthwork bastions flanked the western outer wall.

Inside the castle, the engineers built new gunpowder magazines and equipped the great tower as a vast store for gunpowder, shot and other military supplies. When war ended in 1815, Dover Castle was a formidable artillery fortress and barracks.

The 19th century

After 1815, there were nationwide reductions in military expenditure. At Dover Castle, the Army vacated many of its barracks, including the underground casemates, which were used from 1818–28 by an anti-smuggling force, the Coast Blockade.

However, by the late 1840s the nation’s defences were in a parlous condition and improvements slowly followed. In 1853 the inner bailey and great tower were strengthened. This was followed by the magnificent Officers’ New Barracks in 1856, to a design by Anthony Salvin, and by better buildings for the soldiery – including new barracks at the East Casemates, the Regimental Institute (now the NAAFI) (1868) and the Garrison School (1870).

From 1865 the building of a new fortress, Fort Burgoyne, to the north was a final acknowledgement of the weakness of the Spur. But the castle found a new role in coast defence, with four groups of large guns (Hospital, Shot Yard, East-Demi and Shoulder of Mutton batteries) built in 1871–4 along the cliff edge. They were capable of firing far out to sea against the new threat of steam-driven ironclad warships.

The First World War

When Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Dover Harbour became the home of the Royal Navy’s Dover Patrol to defend the Dover Strait, particularly against German submarines, and to protect communications for the Army in France and Flanders.

Dover had a garrison of around 16,000 troops, with the castle as headquarters, to defend a perimeter occupying the high ground around the town for up to 1.5 miles distant. Within the perimeter were many training camps for soldiers destined for the Western Front.

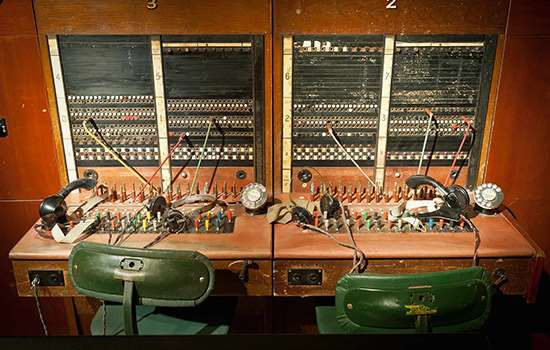

The harbour approaches were defended by coast defence guns, while the new threat from airships and airplanes was addressed by anti-aircraft guns, including two near St Mary in Castro. Entry to the harbour was regulated and the control building, the Fire Command Post (established in 1905) and Port War Signal Station (1914), survives in Dover Castle, with a commanding view over the Channel.

Take a virtual tour of the Fire Command PostThe Second World War

In 1939, Dover resumed its former role when war came again, with the castle as headquarters, but for the Army garrison defending the town, and for the re-established Royal Navy base. The empty underground casemates were re-commissioned as bomb-proof offices for the vice-admiral in charge of the naval base, and as headquarters for army units co-ordinating coast artillery and anti-aircraft defences and for the units defending the Dover fortress.

These commands expanded throughout the war, as Dover became the nearest town to enemy-occupied territory in June 1940. Vice-Admiral Ramsay’s naval headquarters played a central role in Operation Dynamo, with the evacuation of 338,226 British and Allied troops from Dunkirk.

Two new levels of tunnels were built (the old ones were now called Casemate level). The first, called Annexe, was completed early in 1942 as a small hospital. The second, called Dumpy, opened in 1943 as a Combined Headquarters (CHQ) with provision for large-scale communication transmission. The latter played a significant role in Operation Neptune, the naval side of the plan for D-Day, and also in a successful deception operation known as Fortitude South, which convinced the Germans that the main invasion of Europe would be in the Calais area, not Normandy, and that it would be launched from the Dover area.

The Cold War

The Army vacated the castle in 1958, except for Constable’s Gate which remained as a senior officer’s residence until 2015. In the early 1960s the government selected Dover Castle as one of 12 Regional Seats of Government, to be occupied in the event of nuclear war. It was to be in the charge of a senior minister, with a military and civilian staff, tasked with creating some form of administration after a nuclear attack.

The heart of this was in Dumpy level, with Annexe refitted as a dormitory and the western tunnels of Casemate repurposed as dormitories, dining and catering areas and rest rooms. The complex was sealed against contamination and given air filtration and communications equipment including a small radio broadcasting studio. It was decommissioned in the early 1980s.

By Paul Pattison

Find out more

-

The Roman Lighthouse at Dover Castle

Find out more about the Dover pharos, one of only three Roman lighthouses to survive from the whole of the former Roman Empire.

-

Thomas Becket, Henry II and Dover Castle

Discover why Henry II spent a fortune on Dover Castle – not to protect his kingdom, but to save face after the murder of Thomas Becket by Henry’s own knights ten years earlier.

-

The Sieges of Dover

Read about the two sieges of Dover in 1216 and 1217 during King John’s reign, and the circumstances that gave rise to this attack.

-

Eleanor de Montfort and the Siege of 1265

Caught up at the centre of a civil war, Eleanor de Montfort held Dover Castle against the king in 1265 after her husband and eldest son were killed in battle.

-

Dover Castle: The Georgian Fortress

Read about Dover Castle’s transformation into a permanent barracks and artillery fortress in the Georgian era, a role that continued into modern times.

-

Fortress Dover and the First World War

Use our virtual tour to explore a building at Dover Castle that played a vital role in safeguarding Dover as a garrison and naval base in the First World War.

-

Operation Dynamo: Things You Need to Know

Find out the key facts about Operation Dynamo, the near-miraculous evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940, which was controlled from Dover Castle.

-

The Fall of France in 1940

On 22 June 1940 the French government surrendered to Hitler, just six weeks after the Germans’ initial advance westwards. Find out why France collapsed so quickly.

-

D-Day Deception: Operation Fortitude South

In 1944, Dover Castle’s tunnels played a supporting role in an elaborate deception that concealed the true location of the D-Day landings from the Germans.

-

Wartime Tunnels Collection Highlights

From weapons and technology to uniforms and personal possessions, these objects provide a glimpse into the lives of those who served in the castle’s tunnels.

-

Plans of Dover Castle

Download these PDF plans of Dover Castle to see how this great fortress has evolved over time.

-

Buy the Guidebook

Packed with plans, reconstructions and historic images, this guidebook tells the story of how the castle’s defences were adapted over 800 years.