As the man behind some of England's most iconic gardens, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown is remembered for the radical transformations he made to the landscapes of country estates in the mid-eighteenth century.

He was apparently nicknamed ‘Capability’ because he had a tendency to inform his clients that their estates had great ‘capability’ for improvement. Brown removed the formal geometric designs of the 17th century, replacing them with rolling lawns, informal planting and serpentine rivers. He also usually operated on an immense scale, creating sweeping carriage ways into the wider landscape (known as ‘ridings’), planting woods and carefully using garden buildings (called ‘eyecatchers’) to focus a view.

At English Heritage, we are fortunate to care for several of Capability Brown’s most intriguing commissions, including Audley End, Appuldurcombe, Wrest Park and other properties that form an ‘eyecatcher’ in a much wider landscape setting created by Brown. In 2016, we celebrated the 300th anniversary of his birth, and you can find his blue plaque at Wilderness House.

Turning his designs into reality was a major commitment: it took years to complete the work on some gardens, and even longer for them to grow to maturity. Here’s our guide to what you'll need in order to transform your garden in line with the visions of Capability Brown.

1. Plenty of space

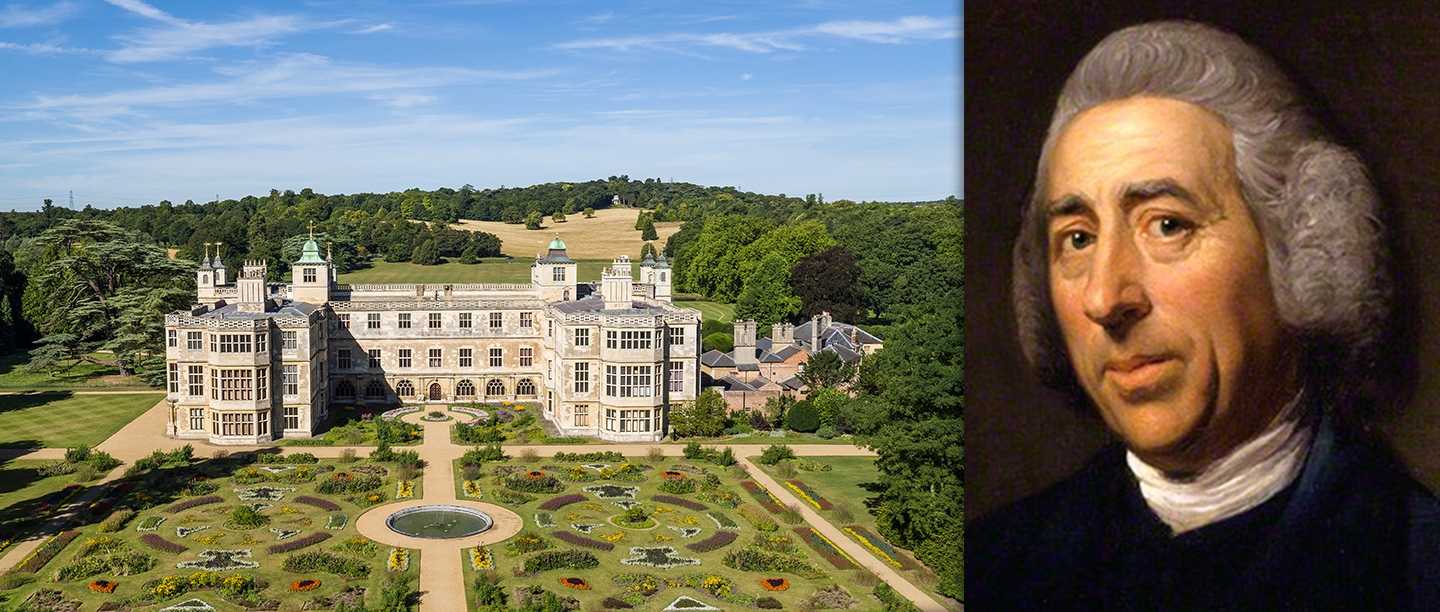

The stone bridge and house at Audley End © Historic England

Audley End is often described as a ‘Capability’ Brown landscape in miniature. However, it still has all of the features Brown is most famous for, including a ha-ha, sinuous river, sweeping lawn and carriageways, as well as shelterbelts and clump tree planting. For this to be described as ‘miniature’ provides an idea of the scale for which he was usually famous.

At Appuldurcombe on the Isle of Wight (once home to the infamous Lady Worsely), Brown was involved in a much larger scheme from 1779 – almost four times the size of his work at Audley End. He used the existing features in the parkland, built in the early 1770s, including an obelisk and ‘mock’ ruined castle, to form the ‘eyecatchers’ in his design, which included carefully positioned trees and ridings to create set pieces in the landscape.

2. Endless resources

Sherborne Old Castle in Dorset, from above. Capability Brown created the 50 acre lake (left of the image) in 1753 as part of improvements to the grounds of the later Sherborne Castle, which is privately owned.

At Sherborne Castle, Brown’s original contract with Lord Digby in 1753 appears to have been for £300 with further payments making the total payable £853. While it is hard to estimate an exact conversion of this cost to today, it would have been a substantial amount. Although some of Brown’s largest commissions were recorded as costing over £10,000.

In comparison, at Wrest Park, no contract or plan has been found for Brown’s involvement in the late 1770s. The only evidence of Brown’s involvement comes through the letters of the owner Jemima, Marchioness Grey and her daughters. This indicates that Brown simply offered advice to Jemima on the changes to be made which Jemima was then left to carry out using her own resources and existing estate labourers.

3. Infinite patience

Cedar of Lebanon at Audley End, planted by Capability Brown

Working with Brown was not a quick process. Simply removing or adjusting an old scheme and implementing Brown’s new design often took years to complete. In many cases, Brown’s involvement was simply the catalyst to form a new landscape and changes often continued ‘in house’ after the end of his commission.

At Ampthill Park (from which the ‘eye catcher’ at Houghton House is viewed), Brown received payments for work between 1770 and 1775, a period of only 5 years. However, at Wrest Park, Brown is known to have first advised in 1758 and he was still involved in 1779, over 20 years later.

The proposals took a long time to implement, and the timescale of Brown’s work is reflected in the materials he used. Rather than just rely on flowers or shrubs to create an immediate impression, Brown positioned trees to form his compositions. The Cedar of Lebanon in the Mount Garden at Audley End, planted by Brown in the 1760s, is a beautiful surviving example of one of the signature trees that he is famous for.

4. Original ideas

Capability Brown’s landscape design for the gardens at Audley End © Historic England

It is often presumed that Brown simply turned up, pronounced that the landscape had great ‘capabilities’, produced a beautiful plan and then proceeded to lay it out on the ground. But at both Wrest Park and Audley End it is clear that the owners were involved in the design of the final scheme. Jemima writes to her daughter in 1779 requesting she discuss plans with Brown for the Grove but adding ‘don’t let him in any way shorten the terrace at that corner of the Grove.’

At Audley End it would appear that the design was agreed between Sir John Griffin Griffin and Brown before the contract was drawn up. Within the contract it states ‘Lady Griffins Garden in all its parts to be made according to the plan and ideas fixed on with Sir John’. In this case it is clear that Sir John and Brown had spent time at Audley End discussing the changes to be made to the garden and agreeing their final form.

5. A good relationship…

Sir John Griffin Griffin by West. Capability Brown was commissioned to improve the gardens at Audley End after Sir John inherited in 1762 © Historic England

At Wrest Park Jemima and her family appear to have had a close relationship with Brown. In 1773 Jemima’s daughter, Mary, had tea with Brown which was ‘occasioned by a promise he had made some time, of showing us his Hothouses at Hampton Court.’ From the family’s letters it is clear that they had more than a working relationship with Brown.

This familiar relationship at Wrest is in direct contrast with Brown’s relationship with Sir John at Audley End. Their relationship deteriorated as a result of unmet completion dates, a dispute over payment and dissatisfaction with the work as completed. The final letters between them are written stiffly and formally in the third person. With Brown’s final letter stating that ‘Mr Brown will never labour more to convince Sir John as he knows there is non so blind as him that will not see.’

More to explore

-

Gardening Tips

Taking tips from the past, here are our historic gardeners' top tips for protecting your plants and produce at home.

-

Below Stairs at Audley End

What were Victorian servants’ lives really like? Discover the stories of the men, women and children who worked at Audley End House in the 1880s.

-

Places with Literary Links

If you're a book-lover, artist, or poet, our guide to sites with links to English literature should give you plenty of inspiration.