The fort’s development

The fort dating from the AD 120s was built of stone, but excavations in the early 20th century revealed that an earlier fort had preceded it. This early fort, which was built of timber and lay beneath the eastern half of the second fort, was probably only occupied for a short period, no longer than about 25 years.

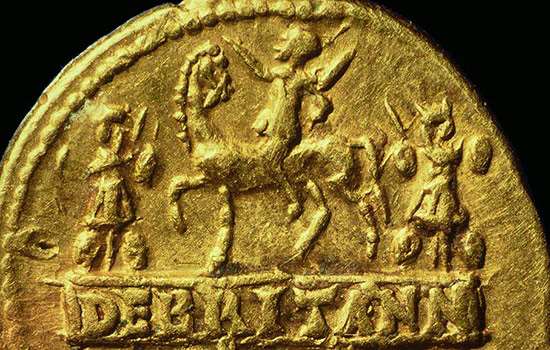

The second, stone fort lasted much longer. Coins found at the site suggest that it was occupied continuously for almost three centuries and only abandoned well into the 4th century AD.

Little is known about the fort’s history, including the identity of any of the units stationed there: neither of the two stone inscriptions found at Ambleside includes the name of a garrison. The fort’s Roman name is also uncertain. It may be the fort called Galava – meaning ‘fort beside a forceful stream’ – in Roman documentary records. Recent research, however, has suggested that Ambleside’s Roman name could instead have been Clanoventa (or Glannoventa), which means ‘market on the water’ (although that name is also associated with the fort at Ravenglass).

The Romans in the Lake District

Ambleside was one of three forts joined by a road that secured Roman control of communications across the Lake District. The Roman army had rapidly established control over the south and east of Britain after the invasion of AD 43, and from around AD 70 they advanced into northern England. However, at this stage they bypassed the Lake District, instead marching north from Chester into Scotland.

It was only after the Romans retreated to a frontier between the river Tyne in the east and the Solway Firth in the west that the army pushed into Cumbria. In around AD 90, they built forts at Ambleside and Watercrook.

Emperor Hadrian overhauled the empire’s frontier strategy and completely reorganised the garrison of Roman Britain. Most dramatically, from AD 122 Hadrian’s Wall was built to control access from the north. It included a chain of installations protecting the Cumbrian coast. Early in Hadrian’s reign, forts were also built at Ambleside (replacing the earlier fort) and Hardknott, along with a small fortlet at Ravenglass on the coast. These forts controlled the route down the Esk Valley, and access to the coast and the wider road network.

Later in Hadrian’s reign the fortlet at Ravenglass was replaced by a large permanent fort. With forts at either end of the road, Hardknott Fort then became redundant and went out of use. The forts at both Ambleside and Ravenglass, and their surrounding settlements, remained thriving communities until Roman rule in Britain ended in about AD 400.

Layout and defences

Roman forts usually had a regular layout and plan, and the stone fort at Ambleside was no different. It sat on a large rectangular platform and was encircled by strong walls, with towers at the corners and gateways. Today, the edges of the fort’s platform can only be seen by keen-eyed visitors as slopes in the landscape, though they are clearly visible from the air.

The remains of the eastern and southern gates can still be seen, as can the north-eastern and south-eastern towers. On the northern and eastern sides there were two V-shaped ditches, which worked in conjunction with the walls to impede attackers. Normally such ditches encircled the fort entirely, but on the southern and western sides the river and lake made ditches unnecessary.

An impressive double gateway – the porta praetoria – in the eastern wall acted as the main entrance. Pivot holes for the large wooden doors can still be seen, as well as the foundations of the square flanking towers that protected the gateway. The south gate had a single entrance – the pivot holes in the threshold for its massive wooden doors are also visible – and the road through it led to the nearby lakeside.

Move the slider to see an outline of the fort’s buildings as they may have looked in the Roman period, overlain on an aerial view of the fort remains

The main buildings

A road led from the eastern gate down the centre of the fort to its three most important buildings – the headquarters, the granaries and the commander’s house. These buildings formed the central range of the fort and were used for many important tasks including administration, food storage and religious ceremonies.

The principia (headquarters) was the administrative and sacred heart of a Roman fort. Beyond a guarded doorway to the street was a courtyard. It was the fort’s equivalent of the small forum in a Roman town – where gatherings were held to talk of politics or military plans, or to conduct any other important business.

Beyond this was a more elaborate doorway into a basilica – a large, high-roofed hall where gatherings could be held. Here the commanding officer could issue orders, justice was meted out, and religious ceremonies could be held.

Opening off the rear of the hall were smaller rooms for administration and record keeping. Here too was the most important space in the fort, the aedes (shrine), where the unit’s standards were kept along with images of the emperor, who was worshipped as a god.

Beneath the shrine, a sunken strongroom or treasury – which visitors can still step down into today – held the garrison’s funds and soldiers’ money. The gods of the shrine above were thought to protect it and keep any thieves away.

Next to this are the partially excavated remains of the praetorium (commander’s house), which consisted of at least 12 rooms around a central, open courtyard. This was where the commander lived with his family. The size and complexity of the house demonstrated his high status – he would have been a wealthy Roman citizen from the upper ranks of society. This was markedly different from the cramped and narrow barracks, each housing eight soldiers in a few square metres of space.

On the other side of the principia were two large, long rectangular buildings – the fort’s granaries. Their remains provide clues that reveal how their design helped preserve the food (not just grain) which was kept inside. The short buttresses projecting outwards from the external walls provided support for the walls holding up the heavy slate roof. Inside are the remains of low walls that run the length of the building. These once held up a raised floor, under which air could circulate to help keep the food cool and dry.

The barracks for the garrison would have been at the rear and front of the fort, but they are no longer visible, probably because they were built of wood.

An attack on the fort?

An inscription on a tombstone found to the east of the fort reveals a fascinating story of violent death at Ambleside. It records the names of two men. The first, Flavius Fuscinus, was a retired soldier who died aged 55. He was probably living as a veteran with his family at the settlement. Below his name is that of his son, Flavius Romanus, who served in the garrison as a soldier and senior clerk. He died at the age of 35.

The last part of the inscription reads: ‘Killed by enemies inside the fort.’ It is difficult to tell whether this refers to both men or only to the son. Either way, the specific mention of the death occurring ‘inside’ the fort is the only known record from anywhere in the Roman Empire of a soldier or soldiers dying by enemy hands within a Roman fort. The words ab hostibus (‘by enemies’) imply enemy action rather than a personal enmity.

The tombstone demonstrates that living inside a heavily defended Roman fort did not guarantee protection. The inscription is relatively poorly made, which may suggest that the tombstone was made in a hurry, perhaps during a period of hostilities.

Image: the tombstone of Flavius Fuscinus and Flavius Romanus, now in the Armitt Museum, Ambleside

© Courtesy of the Armitt Trust

Beyond the fort walls

Roman forts were not only occupied by soldiers. Outside them, settlements usually developed. These would have been populated by the soldiers’ families, retired veterans, or simply merchants, shopkeepers and craftspeople who supplied and traded goods with the soldiers.

Remains of such a settlement have been found near the fort at Ambleside. It seems to have been quite large, possibly extending up to 300 metres to the north of the fort, where some simple wooden buildings have been excavated. Excavations of similar settlements have demonstrated that they typically comprised rectangular roadside buildings that incorporated shopfronts, workshops and accommodation. Other likely buildings might include temples, and the fort’s bath house was often located within the settlement, near a suitable water source.

Several items discovered here give us a glimpse into life in Roman Britain, including remnants of leather shoes, sherds of pottery, coins and a brass colander (the Romans often used brass for kitchenware).

Ambleside’s connections

The many Roman towns and forts across Britain were linked by a comprehensive road network. Although Ambleside was remotely located, at the heart of a mountainous landscape, it was well connected to other forts in the area. Such links facilitated trade and the movement of soldiers and supplies. Ambleside was at the meeting point of at least two roads: as well as the one running west to Ravenglass on the coast, another ran north-east, to meet the major north–south road running through western Britain near modern-day Penrith.

Rivers and the sea were also essential for travel in the Roman world, particularly for trading over long distances. Ambleside lay at the point where the Rothay and Brathay rivers – both major water routes – emptied into Lake Windermere. Today, the fort’s southern gate lies close to the lake shore, and although it isn’t certain where the shoreline was during the Roman period, it may have been even closer then. Its proximity would have been an important factor in the choice of the fort’s location.

The unusually large size of the granaries is perhaps one of the most striking features of the fort – they would probably have held a lot more food than was required for the 500 soldiers based at Ambleside. Perhaps this indicates that the fort was something of a supply hub for garrisons elsewhere. One of the possible options for Ambleside’s Roman name – Clanoventa (‘the market on the water’) – also suggests that it may have been an important trading centre.

Find out more

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out more about the network of forts and roads that the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Visit Ambleside Roman Fort

The well-marked remains of a 2nd-century fort with large granaries, built under Hadrian's rule to guard the Roman road from Brougham to Ravenglass and act as a supply base.

-

Listen to our audio guide

Our audio guide to the fort at Ambleside is designed to be enjoyed whether you are visiting the fort or just want to listen at home or elsewhere.

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

Further reading

RH Leech, ‘The Roman fort and vicus at Ambleside’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Archaeological and Antiquarian Society, 93 (1993), 77–95

D Mann and A Dunwell, ‘An interim note on further discoveries in the Roman vicus at Ambleside’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Archaeological and Antiquarian Society, 95 (1995), 79–83

T Pearson, Ambleside Roman Fort, Cumbria, Archaeological Investigation Report Series 2/1998 (English Heritage, 1999)

DCA Shotter, ‘Three Roman forts in the Lake District’, Archaeological Journal, 155 (1998), 338–51