History of St Botolph’s Priory, Colchester

Founded between 1093 and 1100, the priory of St Julian and St Botolph was one of the first religious houses in England to adopt Augustinian rule. This initially gave it authority over other houses of that order in the country to correct abuses, inflict punishments and prescribe regulations.

Despite these privileges, St Botolph’s remained a small foundation and fund-raising must have been hampered by the existence of the more powerful St John’s Abbey a few hundred yards to the south. Its relative poverty means construction would have been a slow process, and the details of the west front indicate a completion date of around 1150.

When St Botolph’s was dissolved in 1536 its possessions were granted to Sir Thomas Audley, the Lord Chancellor.

Part of the church remained in use as a parish church until the seige of Colchester in 1648, when the Royalist town was attacked by General Fairfax. During the seige the church was largely destroyed by cannon fire and has never been repaired.

The nave was used for burials during the 18th and 19th centuries and south of the church the cloister was at one stage laid out as a garden.

Description

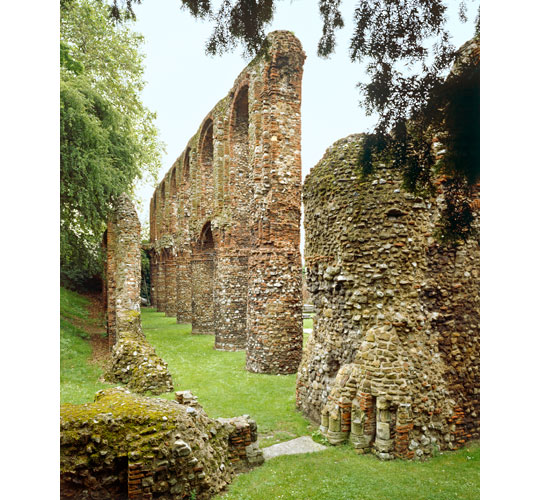

Even in its ruined state the priory church is an impressive example of early Norman architecture, and the elaborate west front is one of the best surviving examples from this period.

It had flanking towers to the north and south, unusually placed outside the nave aisles, and three doorways. The decoration on these – their mouldings and chevron ornament – are carried out in good quality limestone, but the individual stones are small and were evidently used with great economy.

Two rows of interlacing Roman brick arches originally ran continuously across the front between the towers. The remains of a large circular window just touching the top of the upper tier, in the middle of the façade, still has chevron ornament around its outer edge. Within this are traces of the rebate for the wooden frame that held the glazing. What remains of the upper levels of the west front indicate this richness of decoration continued all the way to the roof.

The church was built of flint rubble with arches and dressings in brick – the latter mostly reused from Roman buildings at nearby Colchester. Though simple in design the massive piers and arches of the nave are stunning in effect. The circular piers are strength-ened by triple courses of brick and the shallow pilasters running up from their capitals mark the division of the bays and the position of the roof tie-beams.

The masonry would originally have been plastered over inside and out and probably painted to imitate ashlar blocks; an effect that can be seen on the similar piers at St Albans Abbey. The base of a wall across part of the south aisle shows there was a chapel at this point, but other than that the internal arrangements of the church have been lost.

The fragments of a medieval glazed tile pavement in this aisle are probably not in their original position. Much of the north range of the cloister has been uncovered including the remains of its stone bench.

Further Reading

Crossan C, Crummy, N, and Harris, A, ‘St Botolph’s Priory’, The Colchester Archaeologist, 5 (1992), 6–10

Peers, C, St Botolph’s Priory, Colchester, Essex (English Heritage, London, 1977)