When was Hadrian’s Wall built?

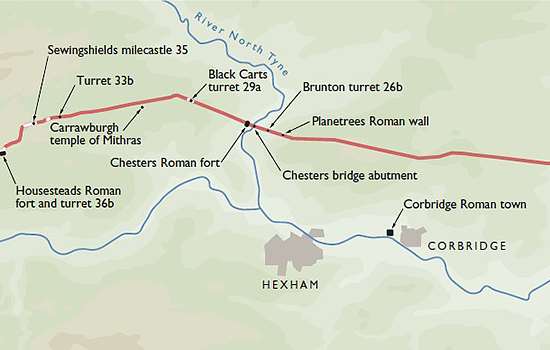

Permanent conquest of Britain began in AD 43. By about AD 100 the northernmost army units in Britain lay along the Tyne–Solway isthmus. The forts here were linked by a road, now known as the Stanegate, between Corbridge and Carlisle.

Hadrian came to Britain in AD 122 and, according to a biography written 200 years later, ‘put many things to right and was the first to build a wall 80 miles long from sea to sea to separate the barbarians from the Romans’.[1]

The building of Hadrian’s Wall probably began that year, and took at least six years to complete. The original plan was for a wall of stone or turf, with a guarded gate every mile and two observation towers in between, and fronted by a wide, deep ditch. Before work was completed, 14 forts were added, followed by an earthwork known as the Vallum to the south.

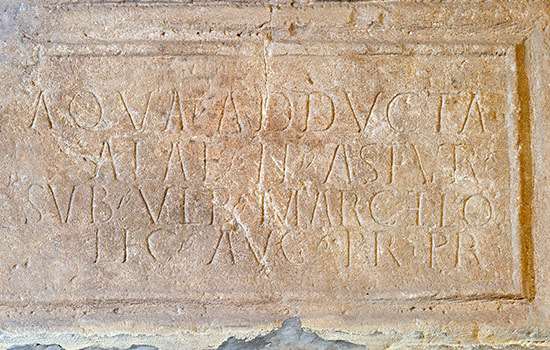

The inscription on the Ilam pan, a 2nd-century souvenir of Hadrian’s Wall found in 2003, suggests that it was called the vallum Aelii, Aelius being Hadrian’s family name.

Read more about Emperor HadrianThe First Design

The Wall was placed slightly north of the existing line of military installations between the river Tyne and the Solway Firth. Its line was carefully chosen to make best use of the topography, and it was surveyed from each end towards the middle, or rather towards the crags, in sections.[2] Building in the east started at the point where the road from the south, Dere Street, met the Wall and where later a gate, the Portgate, was erected.

As first planned, most of the Wall was to be built in stone, but the western 30-mile section was in turf. In front of both was a substantial ditch, except where crags or rivers made this unnecessary. At each mile a gate was protected by a small guard post called a milecastle.

Between each pair of milecastles lay two towers (turrets), creating a pattern of observation points every third of a mile. The stone wall, with a maximum height of about 15 feet (4.6 metres), was 10 Roman feet (3 metres) wide, wide enough for there to have been a walkway along the top, and perhaps also a parapet wall. The turf sector was 20 Roman feet (6 metres) wide.

To the north of the turf sector lay three advance forts, all probably part of this plan, but otherwise the forts remained on the Stanegate behind the Wall.

A change of plan

Before the first plan was completed, a radical change led to the placing of forts on the wall line and down the Cumbrian coast, and the construction of an earthwork to the south.

The forts, each apparently built for a single unit and at a basic spacing of 7⅓ miles, were placed astride the Wall wherever possible. This allowed three main gates, each with two entrances, making the equivalent of six milecastle gates, to provide access to the north; the double-portal south gate was supplemented by two small side gates. The position of the forts and the provision of so many gates suggest that a requirement for increased mobility led to this change.

The addition of the forts was followed by the construction of an earthwork to the south 120 Roman feet (an actus – about 35 metres) wide. This consisted of a central ditch between two mounds. Causeways, surmounted by gates, were provided at forts. The purpose of the Vallum, as this earthwork is known, was presumably to protect the rear of the frontier zone.

After the forts had been added, the width of the Wall was narrowed to 8 Roman feet (2.4 metres) or less and the standard of craftsmanship reduced, both presumably in order to speed work.

Who built the wall?

Hadrian’s Wall was built by the army of Britain, as many inscriptions demonstrate. The three legions of regular, trained troops in Britain, each consisting of about 5,000 heavily armed infantrymen, provided the main body of men building the Wall, but they were assisted by the auxiliary units – the other main branch of the provincial army – and even the British fleet.

The complex building programme took many years to complete. It is possible that it started before Hadrian’s arrival in Britain in AD 122 and that the major change in plan was a result of his intervention.[3]

Who manned the wall?

Although mainly built by legionaries, the Wall was manned by auxiliaries. They were organised into regiments nominally either 500 or 1,000 strong and either infantry or cavalry or both. The 500-strong mixed infantry and cavalry unit was the workhorse of the frontier. Each fort on the Wall appears to have been built to hold a single auxiliary unit.

The troops based in the forts and milecastles of the Wall were mostly recruited from the north-western provinces of the Roman empire, though some were from further afield.

Army units tend to be accompanied by camp followers. Little is known about these people in the early years of the Wall; it would appear that they were not allowed to settle in the zone between the Wall and the Vallum. Excavation has demonstrated the existence of civil settlements in the 3rd century and geophysical survey has recorded the urban sprawl spreading well beyond the forts.[4] These remains are undated, however.

Find out more about legions and auxiliariesThe wall after Hadrian

Hadrian’s death in AD 138 brought a new emperor to power. The emperor Antoninus Pius abandoned Hadrian’s Wall and moved the frontier up to the Forth–Clyde isthmus, where he built a new wall, ‘this time of turf’[5] – the Antonine Wall. This had a short life of about 20 years before being abandoned in favour of a return to Hadrian’s Wall.

Hadrian’s Wall had been slighted when it was abandoned, with milecastle gates removed and crossings thrown across the Vallum ditch. Now all was brought back into working order, though the work of reconstituting the Vallum was never finished. A road was also added to the frontier.

Hadrian’s Wall appears to have continued in this form into the late 2nd century. A major war took place shortly after AD 180, when ‘the tribes crossed the Wall which divided them from the Roman forts and killed a general and the troops he had with him’.[6] We know no details of the subsequent fighting, but it probably led to changes to the Wall, including the abandonment of many turrets in the crags sector and a redeployment of the army.

We can see this most clearly in the early 3rd century. At this time, the cavalry units were grouped round the two main roads to the north at the Portgate on Dere Street and beside Stanwix by Carlisle, and along the roads to the south. North of the Wall there were now four advance forts, two on each side of the country. The eastern forts each held a 1,000-strong mixed regiment of infantry and cavalry, an irregular unit and scouts.

In the late 2nd or early 3rd century, many milecastles had their north gates narrowed so that they could only be used by pedestrian traffic, while a major repair to the Wall itself took place.

The forts on Hadrian’s Wall had a long life of nearly 300 years. Many modifications took place, to the barrack blocks, the headquarters buildings and the commanders’ houses in particular. Some forts became overcrowded with buildings; others acquired open spaces. So far as we can determine, all continued to the end of Roman Britain, that is into the early 5th century. The latest coins found on Hadrian’s Wall were minted in AD 403–6.

After the Romans

With the abandonment of Britain by the central authorities, it is less clear what happened. At Birdoswald, a case had been made for life at the fort continuing, with the regimental commander perhaps turning into a local chieftain.[7]

In the years that followed, Hadrian’s Wall became a quarry for the stone to build castles and churches, farms and houses along its line, until the conservation movement in the 18th and 19th centuries put a stop to that. It was only from the mid 19th century onwards that early archaeologists and historians such as John Clayton, John Hodgson and John Collingwood Bruce began to study Hadrian’s Wall in earnest and sought to protect its still magnificent remains.[8]

To read more about this see Research on Hadrian’s Wall.

About the Author

David Breeze is former Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments for Scotland and Visiting Professor of Archaeology at the University of Durham. He is the author of the English Heritage guidebook to Hadrian’s Wall and co-author of Hadrian’s Wall, the standard work on the Wall.

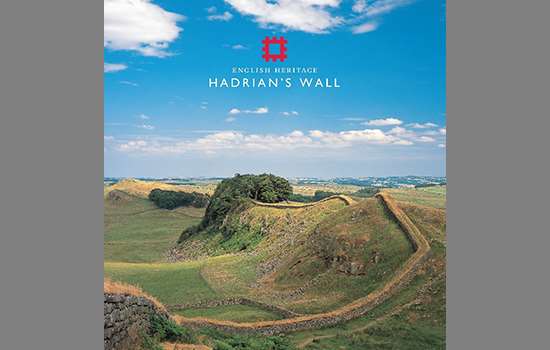

Buy the guidebook to Hadrian’s Wall