The Haitian Revolution, slavery and the Transatlantic World

The drama of the Haitian Revolution began in earnest in 1791. In August of that year, enslaved people revolted in what was then French-controlled Saint-Domingue. It was the richest colony in existence, producing much of the Atlantic world’s sugar and coffee. Revolution and armed struggles spread in the following years, as the Caribbean also became the scene of general warfare between European powers, including Britain, France, and Spain.

In September 1793, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, a commissioner sent to Saint-Domingue from France, responded to the growing unrest by formally recognising the emancipation of enslaved people in the colony’s northern province. In February 1794, the French Revolutionary Republic declared the end of slavery throughout the French colonial empire.

Eight years later however, in 1802, Napoleon attempted to re-instate slavery. His troops succeeded in much of the empire, but Saint-Domingue rebuffed French armies and claimed its independence in 1804. The historic moment was symbolised by adopting what had been the indigenous name for the island of Hispaniola: Haiti.

Portchester and Haiti

Portchester is over 1,500 miles from Haiti, and seemingly far removed from its sugar plantations. However, Britain, like many other European countries, had plantation colonies in the Caribbean that relied on the labour of enslaved people, and were a central part of its empire. While the uprisings in Haiti inspired enslaved people throughout the Caribbean, they terrified individuals and governments that profited from Atlantic slavery, and Britain sought to reinforce its colonial power.

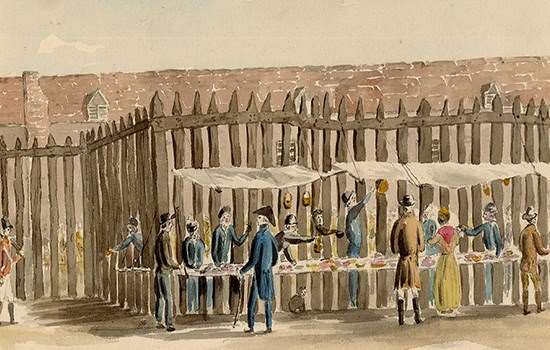

One island affected by the Haitian Revolution was St Lucia, where enslaved people rebelled in the 1790s. British troops invaded the island shortly after France officially abolished slavery throughout its empire. After two years of conflict and guerrilla warfare, Britain fully claimed St Lucia and took black and mixed-race soldiers as prisoners. In May 1796, close to 2,500 of these prisoners arrived in Portchester.

Many of the prisoners left Portchester in 1797, usually going either to France or back to the Caribbean. All prisoners of war were finally released in 1802, when the Treaty of Amiens ended war between Britain and France. However, a new set of French prisoners arrived in the area soon after war resumed in 1803. They were almost all white, and included people who had not fought against slavery, but had in fact been part of Napoleon’s failed effort to reimpose it in Haiti.

Revolution on Stage

While held in the castle and the prison hulks (prison ships) in nearby Portsmouth Harbor, prisoners of war sometimes performed plays. In 1807, the white French prisoners put on The Revolutionary Philanthropist in one of the hulks. Based on the Haitian Revolution, the play presented the racist views of Creole landowners. The title character, modelled on Sonthonax, is portrayed as a dangerous and fanatical Parisian commissioner.

The 2021 play, The Ancestors, responds to The Revolutionary Philanthropist. Produced by the National Youth Theatre in collaboration with English Heritage’s youth engagement programme, Shout Out Loud, and written by Lakesha Arie-Angelo, it links together the stories of black prisoners of war, the Haitian Revolution, and the spirit of performance at Portchester. Revising the white prisoners’ interpretation of the slave uprisings, it explores what narratives of revolution mean for Portchester in the 21st century.

Below, we accompany the play’s revisiting of the Haitian Revolution by exploring in more depth some of its key events and characters.

The Beginning of Revolution

Colonial Saint-Domingue had roughly equal sized populations of about 30,000 white people and 30,000 free people of colour, and 500,000 enslaved people. These groups were often further divided economically, socially, politically, and geographically. They had different, and often competing, visions of revolution.

White elites initially hoped to benefit from the French Revolution to gain more control over trade and more autonomy from France. Free people of colour sought equal political rights with white people. Such rights could challenge racial hierarchies, or, since some free people of colour themselves owned slaves, reinforce differences between free and enslaved people.

In October 1790, a merchant and free man of colour, Vincent Ogé, returned to Saint-Domingue from France and led an armed uprising, which was dramatically crushed. In May 1791, the French National Assembly granted equal rights to a small number of people of colour – men who could prove they were born to two free parents. Faced with opposition, the decree was withdrawn four months later. On 4 April 1792, the French government finally abolished racial discrimination among free citizens in all of its colonies, but groups of free people of colour continued armed struggles for power.

Revolution led by enslaved people began in August 1791.The spark was a religious gathering at Bwa Kayiman (Bois Caïman), but the uprisings had been planned for weeks in advance. Revolution spread, destroying sugar plantations, and thousands of revolutionaries took up arms. Fires in the city of Kap Ayisyen (Cap Français) in June 1793 proved one major turning point by showing the limits of white authority.

Maroons

People who escaped from slavery in the Caribbean were known as maroons. They formed communities and often lived in remote places where the terrain made it possible for them to evade recapture.

In Haiti, maroon communities challenged the slave order by attacking former masters, freeing family members, passing messages between plantations, and simply surviving outside slavery. The most famous 18th-century rebel leader, Makandal, was part of these communities.

He was eventually caught and horrifically killed in 1758. In 1791, Haiti’s maroon communities would help spread the revolution that eventually overturned colonial rule.

In St Lucia, maroons joined with fugitive French republican soldiers to form the Armée française dans les bois (the French army in the woods) to fight the British. The new play The Ancestors begins with women standing guard in just such a maroon camp on St Lucia, and traces their fates as fighting breaks out. We know from historical records that some members of maroon communities were captured and that some of these were among the prisoners sent to Portchester after British victory.

Rebel Women

Women feature prominently in The Ancestors. The character Breffu is based on a woman enslaved at a plantation in Saint John in the Dutch West Indies, who led an insurrection in 1733.

Women were also deeply involved in revolution in Haiti and throughout the Caribbean in the 1790s and early 1800s. It is difficult for us to fully know their stories, as masters deliberately kept enslaved people illiterate. Women were particularly unlikely to be able to read and write, and much of what we know about their lives thus comes from fragmented records or others’ accounts. But we can get clues, including from accounts of women who accompanied their partners or became prisoners in their own right at Portchester.

Haitian women revolutionaries include Cécile Fatiman, the vodou priestess who, along with Dutty Boukman, helped start revolution at the Bois Caïman gathering. Some Haitian women actively took up arms themselves. These included Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière, who fought to defend the Haitian fort of Crête-à-Pierrot when it was besieged by French soldiers in March 1802, and Suzanne (or Sanite) Bélair, who became a sergeant and then lieutenant in the rebel army of Toussaint Louverture.

Toussaint Louverture

Louverture is the best-known leader of the Haitian Revolution and is often a symbol of it. British and French contemporaries sometimes viewed him as a counterpart to Napoleon Bonaparte. Initially named for Bréda, the plantation where he was born, he adopted the surname Louverture or ‘the opening’ in August 1793.

Louverture became a powerful general leading black forces against French colonists and rivals in Haiti. He repeatedly negotiated with changing governments in both revolutionary France and the Caribbean. On 4 February 1801, the seventh anniversary of the French abolition of slavery, Louverture summoned an assembly to write a constitution. Since St Domingue was still officially a colony, this was also a challenge to French control.

Napoleon soon sought to re-assert French authority and to restore slavery. In 1802, his brother-in-law General Charles Leclerc led an expedition to re-establish slavery in the French Caribbean. Louverture fought back. Under the pretence of talks, he was kidnapped and deported to France, where he died in a prison in the Jura mountains in 1803. He did not live to see Haitian Independence in 1804.

André Rigaud

Haitian revolutionaries were often divided among themselves. These divisions had many roots: they reflected racial fractures, competing hopes for revolution, different ideas about how best to secure freedom and defend Haiti, and power struggles between leaders.

As The Ancestors suggests, one of these rivalries was between Louverture and André Rigaud. Rigaud was a mixed-race man, the son of a white planter and an enslaved black woman. Trained as a goldsmith in Bordeaux, he fought with French troops in the American War of Independence (1775–1785). He championed the rights of free people of colour and became a powerful military leader.

In July 1795, Rigaud and Louverture were both named brigadier generals. They supported competing factions in a power struggle when the commandant of the Haitian city of Cap Français, Jean-Louis Vialatte, staged a coup against the white governor, Étienne Laveaux. Rigaud sided with Vialatte, and Louverture with Laveaux. The two joined forces briefly again, but struggled over what is known as the ‘war of knives’ in 1799. Rigaud left for France, and then became an American prisoner of war in October 1800 when he was captured and detained in Saint Kitts. He would return to Haiti twice more, and died in 1811.

Shifting Alliances and Haitian Independence

Saint-Domingue was surrounded by hostile powers, which were also at war with one another. Haiti occupies only the western half of Hispaniola. The other half, now the Dominican Republic, was then a Spanish colony. Spanish Cuba was only about 60 miles away, British-controlled Jamaica was in striking distance, and other nearby islands were divided among European powers, often changing hands. Haitians also traded uneasily with the new United States.

Insurgents thus had to decide who to trust. In The Ancestors, Louverture and Rigaud argue over whether to ally with royalist Spain or republican France. This represents a series of decisions. Louverture initially sided with Spain, calculating that it was more likely to be victorious than France, which had been made unstable by revolution. Even after Sonthonax declared local emancipation, Louverture hesitated, not trusting the commissioner. He did not switch sides until the February 1794 decree officially ended slavery throughout the French empire.

Louverture’s alliances needed to be repeatedly renegotiated as the political and military situation changed in both the Caribbean and mainland France. Remaining French still seemed logical even after Napoleon Bonaparte came to power, until Napoleon’s government tried to restore slavery in France’s colonies. France reimposed slavery elsewhere, but Haiti succeeded in becoming independent in 1804. Heavy reparations imposed on the new nation by France, and efforts to undermine it by other powers would, however, challenge its long-term prosperity.

Written by Professor Jennifer N. Heuer

Find out more

-

Black prisoners at Portchester Castle

Read the extraordinary story of a group of over 2,500 prisoners of war who were brought to Portchester Castle in 1796 from the Caribbean island of St Lucia.

-

Black people in late 18th-century Britain

How much do we know about other black people living in Britain around the time the prisoners from the Caribbean were being held at Portchester?

-

Prisoners of war at Portchester Castle

During the wars with France between 1793 and 1814, thousands of prisoners of war were held at Portchester Castle. Where did they come from, and what was life like at the castle?

-

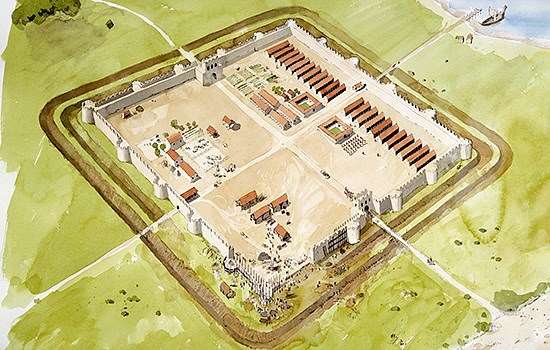

History of Portchester Castle

Read a full history of the castle, from its origins as a Roman fort, through its development as a medieval castle and its role as a prison, to the present day.

-

The prisoners' theatre at Portchester Castle

Find out about the theatre set up and run by French prisoners of war at Portchester Castle between 1810 and 1814.

-

Listen to Speaking with Shadows

In the episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast, Josie Long visits Portchester Castle to learn about the black prisoners of war who were imprisoned there in the 18th century.