The fort at Ravenglass

A small outpost was initially built at Ravenglass during efforts to secure control over the Lake District early in the reign of Emperor Hadrian (AD 117–38). This was later replaced by a large fort.

Little can be seen of this fort today aside from traces of its defences. The northern defences, which were bounded by at least one defensive ditch, are best seen across the fence on the other side of the road from the bath house, while the west defences run parallel to the track. However, excavations have revealed that the fort had a typical layout. The principal buildings stood in the centre, including the principia (headquarters) and praetorium (commanding officer’s house). Barracks for the garrison took up most of the rest of the space.

Some of the barracks were destroyed by fire in about AD 200, although it is uncertain whether this was due to enemy action. They were subsequently replaced, and the turf rampart was strengthened with a stone wall. The garrison stayed in place until the end of Roman rule in Britain in about AD 400.

The site has long been identified as Glannoventa, a name which appears in several Roman documents, but recent finds have suggested that it may have been known to the Romans as Itunocelum.

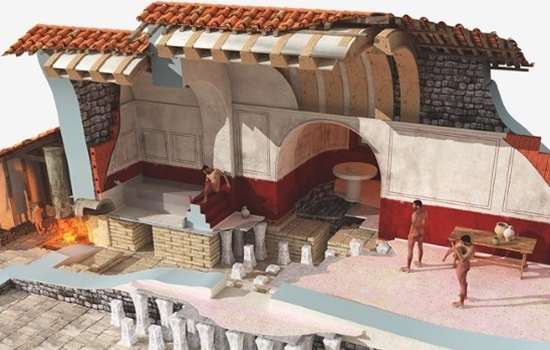

A reconstruction of the fort at Ravenglass (right) and the civilian settlement (left), looking south. The bath house is in the foreground on the left

© Graham Sumner (by permission of the Lake District National Park)

The Romans in Cumbria

Ravenglass was one of three forts joined by a road that secured Roman control of the Lake District. The Roman army had rapidly established control over the south and east of Britain after the invasion of AD 43, and from around AD 70 they advanced into northern England. However, at this stage they bypassed the Lake District, instead marching north from Chester into Scotland.

It was only after the Romans retreated to a frontier between the river Tyne in the east and the Solway Firth in the west that the army pushed into Cumbria. In about AD 90, they built forts at Ambleside and Watercrook.

Emperor Hadrian overhauled the empire’s frontier strategy and completely reorganised the garrison of Roman Britain. Most dramatically, from AD 122 Hadrian’s Wall was built to control access from the north. It included a chain of installations protecting the Cumbrian coast. Early in Hadrian’s reign, forts were also built at Ambleside (replacing the earlier fort) and Hardknott, along with a small fortlet at Ravenglass on the coast. These forts controlled the route down the Esk valley, and access to the coast and the wider road network.

Later in Hadrian’s reign the fortlet at Ravenglass was replaced by a large permanent fort. With forts at either end of the road, Hardknott Fort then became redundant and went out of use. The forts at both Ambleside and Ravenglass, and their surrounding settlements, remained thriving communities until Roman rule in Britain ended in about AD 400.

More about the Romans in the Lake DistrictThe fort garrison

The only unit of the Roman army known to have been connected to Ravenglass was the First Cohort of the Aelia Classica, who were present at the fort by AD 158. They were auxiliaries – soldiers recruited from the large number of non-citizens living within the Roman Empire, who served in return for citizenship for themselves and their descendants. Auxiliaries often had specialist skills, such as archery, horsemanship or seamanship, that were vitally important to the Roman army, and often served across the frontiers of the empire.

Their name provides clues about their origins and their duties at Ravenglass. Aelius was the Emperor Hadrian’s family name, suggesting that the unit was raised during Hadrian’s reign. The term ‘classica’ derives from the Latin ‘classis’, meaning ‘fleet’, indicating that the unit used ships. They presumably protected what was likely to have been a thriving port in the Roman period, when the channel of the river Esk would have been deep enough for boats to moor in the lea of the fort.

We know from a diploma – a record granting citizenship – found at Ravenglass that at least one member of the garrison was a cavalry soldier. So the cohort probably also had a contingent of horsemen – ideal for rapidly patrolling the relatively open plains of the river valley.

The unit’s only known commander (prefect) was Caedicius Severus, who was in charge in AD 158. Unlike the auxiliaries he commanded, he was a wealthy Roman citizen, and Ravenglass was probably the first command of his career. His family name suggests he was from Italy, possibly from Rome or its port, Ostia.

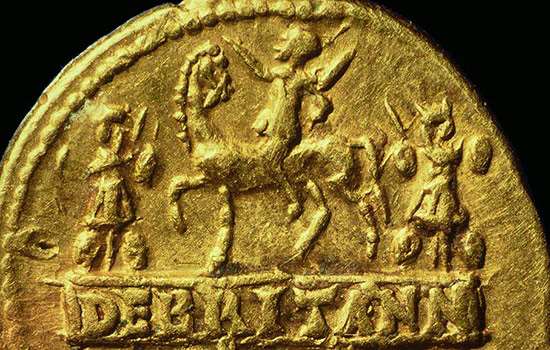

An honourable discharge

In 1995, fragments of a rare bronze Roman document were found (one by a dog) on the foreshore next to Ravenglass Fort. It was a military diploma, a legal document that proved its owner had completed 25 years’ military service and been granted the coveted right of Roman citizenship.

Although the soldier’s name does not survive, the diploma records that he was a soldier in the Aelia Classica, that his father’s name was Cassius, and that he retired in AD 158. He was an auxiliary soldier, and had been recruited into the Roman army in about AD 133. Much of the inscription is lost but he was possibly from Heliopolis in Syria. If so, he may have been recruited to fight against the Jewish uprising there in AD 132 under the emperor Hadrian, before the unit transferred to Britain during the reign of Antoninus Pius (AD 138–61).

There were great benefits to service as an auxiliary. The pay was good, and if a recruit could survive the many risks of being at the sharp end of Rome’s wars, after 25 years’ service he could achieve honesta missio (‘an honourable discharge’) and the honour of citizenship. This was a precious right that he and his family would be able to enjoy in retirement.

The diploma was required as proof of citizenship and would have been kept close at hand. It seems that rather than heading back to his homeland, its owner retired to the settlement around Ravenglass.

The fort bath house

The fort bath house is the only Roman building still visible at Ravenglass. Like many fort bath houses, it sat outside the fort, in this case just beyond the north-east corner.

The impressive remains of four of its rooms stand to a height of almost 4 metres. Visitors can follow in the footsteps of its bathers through its doorways – passing walls that are still lined with rare remains of the original Roman white and pink mortar – and stand beneath its windows. A niche, in what was most likely the changing room, is crowned with a red arch and mortared in white. It may have held a statue of a god or goddess.

Excavations in the 1880s and survey work in the 1980s indicated that the two easternmost rooms were originally much larger, running further eastwards into the field. They contained supports (pilae) for a raised floor, which allowed hot air to circulate beneath, as part of a hypocaust system. They were probably the warm or hot rooms.

Typically, auxiliary fort bath houses would have also had an unheated room, a changing room, hot and cold baths and sometimes fountains.

The siting of the bath house outside the fort raises the possibility that the residents of the settlement around it may have had access to the baths as well as the soldiers.

Roman bathing

Bathing was central to daily Roman life in way that was quite different from modern bathing. The Romans bathed together in bath houses that featured rooms heated to different temperatures and shared baths. They saw bathing as not only crucial to their health, but also an important part of what made them Roman. It was integral to the social life of the community.

The Roman bathing experience involved a process of moving through a sequence of rooms. After undressing, bathers would progress from an unheated room (frigidarium) to a warm room (tepidarium) and then to a hot room (caldarium), before heading back to the unheated room and taking a refreshing dip in a cold plunge pool. They may have worn bathing clothes, including wooden sandals to protect their feet from the hot floors, and carried a toilet kit that included bottles of oil and curved metal blades, called strigils, for scraping oil and dirt from the skin.

Bath houses have been discovered across Roman Britain, from the large public baths of towns and cities, to bath houses at forts like Ravenglass and the private bathing suites of the Roman elite. The people living at Ravenglass were taking part in the same quintessentially Roman practice as their fellow citizens across the empire.

The external settlement

The fort was only one part of the Romano-British community at Ravenglass. Roman forts often attracted large settlements around their walls, and recent archaeological excavations here have revealed that one lay to the east and north. Typical Roman buildings lined the two large roads that ran out of the north and east gates. These buildings usually incorporated shop fronts and workshops as well as domestic space for the owners.

It is likely that families of the soldiers and retired veterans lived here, as well as merchants and craftsmen who would have made a living selling goods to the garrison and trading at the harbour. The community at Ravenglass would have prospered on the economic opportunities created by the needs of the Roman army and relatively high pay of the soldiers. Typically, metalworking would have been in demand and, further up the Esk valley, the Muncaster pottery kilns made tiles for building and pottery for cooking and dining. Amphorae (large jars for transporting liquids such as olive oil and wine) and other imported items found in the settlement, such as Samian pottery from Gaul, most likely arrived at Ravenglass via the sophisticated Roman sea-trading network.

The settlement thrived in the 2nd and early 3rd centuries, but seems to have shrunk in the late 3rd century and possibly gone out of use. During this period military garrisons shrank in size, and the soldiers were paid more in kind, leaving less money for them to spend on goods and services.

Discovery, preservation and excavation

The bath house first attracted the attention of antiquarians in the early 17th century. It was long thought to be medieval, and came to be known as Walls Castle.

The ruins were first recognised as Roman in the late 19th century, when excavations revealed the tell-tale supports of a hypocaust. The ruins were thought to belong to a villa, and were only identified as a bath house in 1919.

The bath house’s survival to such a height is a mystery. One hypothesis is that it was lived in during the medieval period, but there is no evidence of any medieval use.

The fort itself was not so lucky. A railway was built across it in the 1850s and the action of the sea has destroyed its western defences. Excavations in the 1970s revealed part of the fort’s interior, including the barracks, and the fortlet that preceded it.

Mary Fair

Perhaps the most constant and diligent advocate for the study and preservation of Ravenglass was Mary Fair (1875–1955), an archaeologist, author, explorer, photographer and tireless enthusiast for Eskdale’s rich history and traditions.

As a local resident, Mary Fair maintained a watch along the shore and collected and recorded artefacts that emerged thanks to erosion by the sea. She published dozens of articles on the area’s history, including papers on Ravenglass and Hardknott Fort, and the route of the road that joined them. Other more celebrated researchers, such as RG Collingwood, were deeply indebted to her friendship, observations and research.

Mary Fair’s studies of Roman finds and features outside the fort also pointed to the existence of an external settlement. The extent of this was finally proven by excavations by the local community in 2013–15, which revealed that houses and workshops lined the roads leading from the fort.

Find out more

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out more about the network of forts and roads that the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Visit the bath house

The remains of the bath house of Ravenglass Roman Fort, established around AD 130, are among the tallest Roman structures surviving in northern Britain: the walls stand almost 4 metres high.

-

Listen to our audio guide

Our audio guide is designed to be enjoyed whether you are visiting Ravenglass or just want to listen at home.

-

Roman Bathing

Read about Roman bathing and discover what Roman bath houses reveal about the culture and people of the time.

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

Further reading

P Bidwell, The Roman Army in Northern England, 1st edn (Newcastle upon Tyne, 2009)

K Blood, Ravenglass Roman Fort, Cumbria, Archaeological Investigation Report Series 83/1998 (English Heritage, 1998)

K Hunter-Mann, Romans in Ravenglass Community Archaeology Project: Excavation Report 2013–15 (ArcHeritage, 2015)

TW Potter, Romans in North-west England: Excavations at the Roman Forts of Ravenglass, Watercrook and Bowness on Solway, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Research Series 1 (Kendal, 1979)