Medieval Architecture

For more than a century after the Battle of Hastings, all substantial stone buildings in England were built in the Romanesque style. Known in the British Isles as Norman, it is a direct descendant of late Roman architecture. It was superseded from the later 12th century by a new style – the Gothic.

Norman style

The chief characteristic of Norman architecture is the semicircular arch, often combined with massive cylindrical pillars. Early Norman buildings have an austere and fortress-like quality. The Chapel of St John within the Tower of London is one particularly early and atmospheric example.

In larger churches, such as Durham Cathedral and the ruined St Botolph’s Priory, Colchester, dizzying sweeps of double or triple tiers of round arches rise above one another, clerestory over gallery over main arcade.

The Norman style appears at its most uncompromising in the great keeps of castles such as Dover and Rochester in Kent and Richmond in North Yorkshire. Surviving domestic examples are far rarer, but include the so-called Jews’ Houses of Lincoln and the Constable’s House within Christchurch Castle, Dorset.

Embellishment

St Mary’s Church, Kempley, Gloucestershire, serves as a reminder that the walls, pillars and arches of many Norman buildings were richly painted. From the early 12th century carved decoration also became more common, as seen in the chevron vault ribs of the ‘rainbow arch’ of Lindisfarne Priory, Northumberland.

Doorways were flanked by rows of columns, and topped by concentric arches often carved with zigzags, or encrusted with signs of the zodiac or animal faces. The capitals (heads) of pillars were also frequently carved – perhaps with scallops, or stylised water-lily leaves like those at Burton Agnes Manor House in Yorkshire.

Wall surfaces might be decorated with tiers of intersecting round arches carved in low relief, as at Castle Rising Castle and Castle Acre Priory in Norfolk and Wenlock Priory in Shropshire.

The rise of Gothic

In the later decades of the 12th century, a new architecture began to appear. Its pointed arches were possibly derived from Islamic buildings seen by crusaders. The style was regarded with contempt by Renaissance historians, who dismissed it as ‘Gothic’ (meaning barbarous).

Initially, the new arches were simply grafted onto Norman features. At the ‘transitional’ church of Buildwas Abbey in Shropshire, for example, the main arches have shallow points while the windows above them are round-headed.

Byland Abbey, North Yorkshire, and Roche Abbey, South Yorkshire, are key examples of the new style’s rapid progress. By about 1200 a fully Gothic style (called Early English by the Victorians) had developed. Distinctive features included narrow pointed lancet windows, and pillars composed of clustered columns and shafts of polished marble. Whitby Abbey and parts of Rievaulx Abbey (both in North Yorkshire) were rebuilt in this style during the 1220s.

Decorated style

The Decorated style was an offshoot of Gothic that developed from about 1290. Its name reflects the elaborate stone tracery of its sometimes very large windows. The west front of York Minster is a fine example.

Sculpted embellishment was also lavished on arches (which were sometimes flattened and cusped, or ‘ogee’) and on column capitals and wall surfaces. Among the most impressive achievements of the Decorated style is the great octagonal ‘lantern’ of Ely Cathedral, raised in 1322–8 above the crossing and invisibly supported by mighty timber struts

Perpendicular churches

In northern Europe, the Decorated style developed into the convoluted and florid Flamboyant style, but the Perpendicular style that developed in the later 14th and 15th centuries in England is distinctively English. It is characterised by soaring vertical lines, huge narrow-traceried windows, far more glass than stone, and exuberant fan-vaulted, hammerbeam or ‘angel’ roofs.

Perpendicular churches are among the greatest glories of English architecture. Tall and light-filled, they were expensive to build. Many (though by no means all) of the finest stand in areas made prosperous by the booming cloth trade, especially East Anglia and Lincolnshire, the Cotswolds and parts of the West Country.

Manifest piety

Some of the biggest churches built or reconstructed in the Perpendicular style served village populations which could never have filled them. They are manifestations of piety and local pride, rather than need.

Many Perpendicular churches contain lavish tombs, erected to ensure that their founders and benefactors would be remembered. Generous souls further secured their salvation by adding almshouses, schools or ‘colleges’ (communal residences for priests) in a matching style, as at Ewelme, Oxfordshire, Tattershall College, Lincolnshire, and Chichele College, Northamptonshire.

Fashionable mansions

Nobles and rising gentry – like the Heydons of Baconsthorpe Castle – also proclaimed their wealth and status by building lavish mansions. These were often built in the style of castles, and surrounded by moats, but were not seriously defensible.

During the later decades of the 14th century there was a fashion for corner-towered rectangular castles like Bodiam in Sussex, Farleigh Hungerford Castle in Somerset and Bolton Castle in Yorkshire. Old Wardour Castle in Wiltshire is, unusually, hexagonal, while Nunney Castle in Somerset is a compact ‘tower house’ in the French style.

Great 15th-century mansions include Tattershall Castle (Lincolnshire) and palatial Wingfield Manor (Derbyshire), both built for Lord Treasurer Ralph Cromwell and significantly embellished with his badge of a bulging purse and his motto, ‘Have I not the right?’

Tattershall Castle is built of brick. This material became increasingly popular in eastern England, where it was also used lavishly for Thornton Abbey Gatehouse, Kirby Muxloe Castle and much of Gainsborough Old Hall. At first imported from Flanders, building bricks were soon being made in England.

Timber framing

Medieval builders regularly used wood as well as stone, and in many parts of England, the main tradition remained timber framing throughout the Middle Ages.

Timber was used not only for modest dwellings and agricultural buildings but also for ambitious town houses and guildhalls, like those in the Suffolk wool town of Lavenham and for the upper storey of York’s Merchant Adventurers’ Hall. The mighty timber hammerbeam roof added to Westminster Hall in 1395–9 by Hugh Herland and Richard II’s master-mason Henry Yevele has a 21-metre span. It is one of the most daring feats of carpentry ever achieved.

Harmondsworth Barn, Middlesex, of 1426–7, one of the largest timber-framed barns ever built in England, must also rank among the architectural wonders of this period.

Medieval stories

-

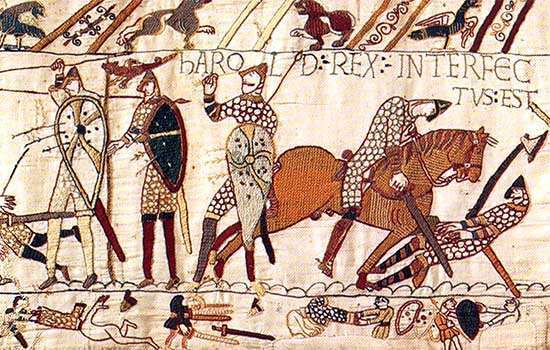

What Happened at the Battle of Hastings?

In the early morning of 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. Find out what happened at the most famous battle in English history.

-

Piers Gaveston and the Downfall of Edward II

Discover how Edward II’s reliance on his ‘favourites’ and possible lovers led to his abdication and death.

-

The Massacre of the Jews at Clifford's Tower

One of the worst anti-Semitic massacres of the Middle Ages took place in York in 1190. The city’s entire Jewish community was trapped by an angry mob inside the tower of York Castle.

-

Lord Hastings, Richard III and an Unfinished Castle

How William Lord Hastings’s ultra-fashionable castle at Kirby Muxloe, Leicestershire, was left incomplete following his summary and shocking execution by the future Richard III.

-

Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Why did Richard, Earl of Cornwall and one of the richest men in Europe, swap three castles for a rock?

-

Where Did the Battle of Hastings Happen?

Historians have long accepted that Battle Abbey was built ‘on the very spot’ where William the Conqueror defeated King Harold. Is there any truth in claims that the battle took place elsewhere?

-

The Misbehaving Monks of Hailes Abbey

Visitation records from abbots who came to inspect Hailes Abbey offer tantalising glimpses into the lives of the monks who lived there and the vices that may have tempted them.

-

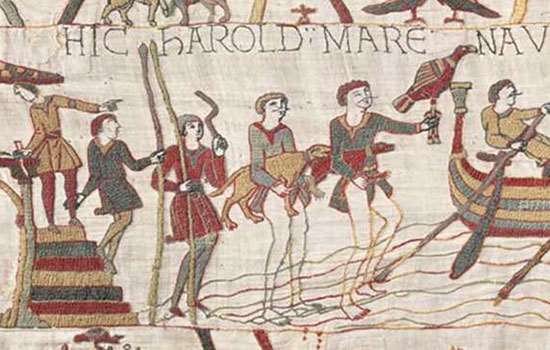

A Canterbury Tale: The Bayeux Tapestry and St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine’s Abbey has long been celebrated for its contribution to English Christianity. But could it also be the birthplace of one of the most famous artefacts in history?

More about medieval England

-

Medieval: Architecture

For more than a century after the Battle of Hastings, all substantial stone buildings in England were built in the Romanesque style, known in the British Isles as Norman. It was superseded from the later 12th century by a new style – the Gothic.

-

Medieval: Religion

The Church was a pervasive force in people’s lives, with the power and influence of the Catholic Church – then the only Church in western Europe – reaching its zenith in England in the Middle Ages.

-

Medieval: Warfare

The Norman Conquest was achieved largely thanks to two instruments of war previously unknown in England: the mounted, armoured knight, and the castle.