The Roman Fort

Portchester Castle was begun as a Roman fort, one of the series of coastal forts now known as the Forts of the Saxon Shore. These forts were built over the course of the 3rd century, to meet the threat presented by Saxon pirates who were then raiding the south coast of Roman Britain.

Portchester is the favoured of two candidates for the Roman Portus Adurni (the other being the lost Walton Castle, in Suffolk), one of a series of forts along the south and east coasts of Britain recorded in a late Roman document, the Notitia Dignitatum. This is a list of military commands and civil service posts across the whole empire: its date is disputed, but is commonly placed somewhere between AD 380 and AD 420.[1]

It seems clear that the fort was founded here because of its commanding position at the head of a huge natural harbour. We have no clear evidence for the date of the original fort, but coins recently found on the site date it to after about 268.[2] Given its evident relationship to the harbour, it may well be that the fort was founded by Marcus Aurelius Carausius, the man appointed by the Emperor Diocletian to command the Roman fleet in the Channel in about AD 285.

Carausius soon fell foul of the tortuous politics of the late Roman empire. When Diocletian’s successor Maximian condemned him to death, Carausius rebelled with the support of the forces under his command, and proclaimed himself emperor in Britain and northern Gaul. Maximian’s deputy, Constantius Chlorus, sent an army against him in AD 293, and in the same year Carausius was assassinated by his deputy, Allectus. Constantius reconquered Britannia for the empire.

The Roman fort here seems to have been fairly constantly occupied up to the end of Roman Britain in the early 5th century. The burial of 27 infants inside the fort suggests that there were substantial numbers of civilians here as well as a military presence. There were timber houses and workshops surrounded by animal pens, cesspits and rubbish heaps within the fort’s walls.[3]

Saxon Portchester

The walls of the Roman fort seem to have housed a community for most of the long period between the end of Roman rule and the Norman conquest of 1066. Evidence of four huts with sunken floors, a well, and signs of ploughing, datable to the 5th century, has been found. In the 7th to 9th centuries a number of timber houses and ancillary buildings were built, perhaps forming two residences. Around the end of the 9th century there seems to have been a break in occupation, with extensive dumping of rubbish over the sites of earlier buildings.[4]

In 904 the Bishop of Winchester gave the fort to the English king Edward the Elder (reigned 899–924).[5] Following this, the fort became a burh – one of a series of fortified places which protected the kingdom from Viking attack.

Archaeologists have found evidence of successive generations of timber buildings from the Anglo-Saxon period within the fort’s walls. In the 10th century a large hall, a courtyard and a stone tower were built within the fort. This suggests that an important man and his family lived here.[6] A cemetery with 21 graves was also found.

The Norman Castle

The Domesday Survey of 1086 states that Portchester comprised three manors before the Norman Conquest.[7] It makes no reference to a fort or castle here, but one of the three manors must have been centred on the Roman fort. This manor was one of the possessions given by William I (reigned 1066–87) to one of his Norman supporters, William Mauduit, with other lands in Portsdown hundred.

By the time Maudit died in about 1100 he had probably laid out the castle’s inner bailey or courtyard in the north-west corner of the vast Roman enclosure. Initially, this probably comprised an outer ditch with a timber palisade, and may have included the first phase of the Norman keep.[8]

After Maudit’s death, the castle and its lands passed to his son, Robert Maudit. But he died in the shipwreck of the ‘White Ship’ off the Norman coast in 1120, and the castle reverted to the Crown. Robert’s daughter, the heiress to Portchester, married another Norman, William Pont de l’Arche, the sheriff of Hampshire. He was an important figure, managing to hold office as sheriff during the reigns of Henry I, his successor, Stephen, and Stephen’s rival for the throne, the Empress Matilda.

The castle’s architectural history in these years is not clear. The first stage of the keep (or great tower) may have been built by Maudit or Pont de l’Arche.[9] At some point in the early to mid-12th century the keep was raised dramatically.[10] Pont de l’Arche also founded an Augustinian priory – a community of priests living together – within the Roman fort’s walls in 1128. This community moved to nearby Southwick in 1150 and its residential buildings were demolished, but their church still stands as Portchester’s parish church.[11] The rest of the fort’s interior was divided into plots and used for farming. Outside the walls, the village of Portchester began to grow up outside the castle’s landward gate.

In 1153 Henry of Anjou, son of the Empress Matilda and claimant to the English throne, granted the castle to Henry Maudit, a descendant of the castle’s founder. This is the first clear documentary reference to the castle.[12] But when Henry ascended the throne as Henry II the following year, he took the castle back, one of many baronial castles he confiscated soon after his accession. It then remained in royal ownership until 1632.

Portchester as a Royal Castle

Portchester was useful to Henry II as an embarkation point when he needed to visit his extensive territories in France, and he stayed there several times. He also used the castle as a prison for important captives, and as a safe haven when shipping his treasury to France in 1163.[13]

The castle was garrisoned from time to time and furnished with supplies. Stone domestic buildings seem to have been built within the inner bailey, with two single-storey ranges on the west side, a hall over a vaulted basement on the north, and a single storey range on the south-east side next to the gatehouse. After this, the buildings seem to have remained largely unchanged for over a century. Meanwhile, across the harbour, the new town of Portsmouth was being founded.

King John (r.1199–1216) visited the castle regularly, and built a new chamber and ‘wardrobe’ here in 1211.[14] With its nearby hunting park in the Forest of Bere, Portchester was an attractive place for royal recreation.

Fearful of French invasion, Edward II (r.1307–27) garrisoned the castle, and between 1320 and 1326 he spent over £1,100 on repairing its buildings. The main Roman gates, the Landgate and Watergate, were remodelled, and the forebuilding of the keep was enclosed with new structures.[15]

The castle continued to be used occasionally by the kings of England as a stopping-place. In 1346 Edward III (r.1327–77) stayed here before crossing to France and winning the Battle of Crécy. His grandson Richard II (r.1377–99) rebuilt the inner bailey as a miniature palace in 1396–9, creating a grand series of royal apartments around its south and west sides.[16]

In 1415 Henry V (r.1413–22) launched another invasion of France from Portchester, which culminated in his victory at Agincourt on 25 October. During his stay here, a plot to depose and murder him – known as the Southampton Plot – was uncovered. It was almost certainly within the castle walls that he confronted the conspirators, who were found guilty of treason and executed.

Portchester was increasingly overshadowed in both economic and military terms by the developing town of Portsmouth, but was chosen as the landing place for Henry VI’s French bride, Margaret of Anjou, in 1445. The castle remained a significant coastal defence under the Tudor monarchs. Elizabeth I (r.1558–1603) held court here in 1603, shortly before the eastern ranges of the inner bailey were completely remodelled by Sir Thomas Cornwallis, the last constable of the castle.

In 1632 Charles I (r.1625–49) sold the castle to a local landowner, Sir William Uvedale, whose descendants, the Thistlethwayte family, still own it today.

Portchester as a prison

Portchester Castle was first used to house captured enemy soldiers in 1665, when England was at war with the Netherlands. The government rented the castle from its owners and housed about 500 Dutch prisoners here. It was used as a prison again during all the major wars of the 18th century, mainly to house French captives. During the War of Austrian Succession (1740–48) Portchester housed around 2,500 prisoners – about a quarter of all the prisoners of war in Britain.

The most important period in Portchester’s history as a prison was that of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars of 1793–1815. Portchester was one of 12 main prisoner-of-war depots in Britain, and housed up to 8,000 prisoners at any one time.

Prisoners of many different nationalities and backgrounds were brought to Portchester in the course of the wars. A group of about 2,000 mainly black and mixed-race prisoners were brought to the castle from the Caribbean in 1796, and remained at Portchester for over a year. Later, a number of prisoners who were among a large group of French captives brought here from the Mediterranean in 1810 transformed one of the rooms in the keep into a theatre. The last prisoners left the castle in May 1814.

Read more about prisoners of war at Portchester

Romantic ruin and historic Monument

After the prisoners left, the army abandoned the castle, and returned it to its owners, the Thistlethwayte family, in 1819.

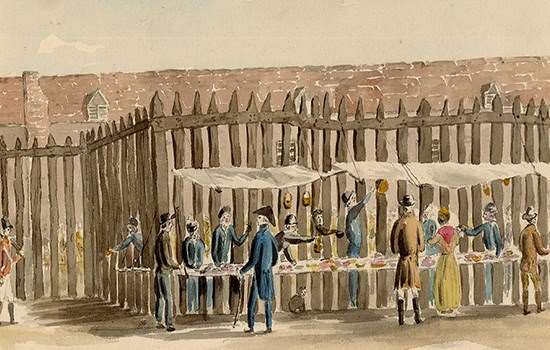

In the 19th century the castle became a tourist attraction, and housed a ‘pleasure garden’, a place of entertainment. At some point in the early 19th century another theatre was established in the keep, but this was on the second floor, two storeys above the room where the French prisoners’ theatre had been. Traces of its painted decoration survive.

In 1926 the Thistlethwaite family decided to place the site in the guardianship of the Ministry of Works as an ancient monument. In the 1920s and 1930s the Ministry cleared vegetation, repaired the walls and excavated the castle’s moats. Many of the workmen were unemployed Welsh miners. In 1984 the site came into the care of English Heritage.

Archaeology at Portchester

Between 1961 and 1979 the castle was the scene of major archaeological excavations directed by Professor Barry Cunliffe. These have transformed our understanding of its long history.

The excavations produced thousands of finds, ranging from prehistoric times to the 19th century. Geophysical survey – which collects information on hidden features without the need for excavation – revealed the presence of many buried features, including the sites of the timber buildings that housed the prisoners of war in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Find out more

-

Prisoners of war at Portchester Castle

During the wars with France between 1793 and 1814, thousands of prisoners of war were held at Portchester Castle. Where did they come from, and what was life like at the castle?

-

Black prisoners at Portchester Castle

Read the extraordinary story of a group of over 2,500 prisoners of war who were brought to Portchester Castle in 1796 from the Caribbean island of St Lucia.

-

Plan of Portchester Castle

Download this PDF plan of Portchester to explore the castle and see how its buildings have developed over time.

-

Buy the guidebook

This guidebook gives a vivid account of the castle’s extraordinary history and its occupants, as well as a full tour of the buildings.

-

Description of Portchester Castle

Read a description of the castle – the walls and towers of the Roman fort and the medieval buildings within it.

-

Why does Portchester Castle matter?

Discover the importance of Portchester’s buildings, from the exceptionally well preserved Roman fort to Richard II’s royal palace.

-

Research on Portchester Castle

Find out how archaeology has informed our understanding of the castle, and what remains to be discovered by further research.

-

Sources for Portchester Castle

Use this list of visual and written sources, published and unpublished, to learn more about Portchester Castle and its history.