Andrew Snape’s House

Ranger’s House stands along the west boundary wall of Greenwich Park, with the expanse of Blackheath to the south. Before the present Ranger’s House was begun, this land was built on by Andrew Snape, Serjeant Farrier to Charles II. Snape was also a developer and a published expert on equine anatomy.[1]As the diarist Sir John Evelyn wrote, he was ‘a man full of projects’.[2]

In the 1670s, without consent, Snape occupied a strip of wasteland between Greenwich Park and Blackheath. Initially he appears to have built stalls for horses grazing on Blackheath, but by about 1688 he had constructed three houses. This included one on the Ranger’s House site.[3]

In 1700 part of this house was occupied by Captain Francis Hosier, who built the core of Ranger’s House as we know it today.

Building Ranger’s House: Francis Hosier

Having joined the Navy at the age of 12 or 13, Hosier progressed through the ranks to the important position of vice-admiral of the blue. Between about 1722 and 1723 he demolished Snape’s house and built a handsome red brick villa of his own, perhaps in response to his new rank.

The location would have been ideal for a Navy man. There was easy access to ships moored along the river Thames, and the Royal Hospital for Seamen was nearby.[4] In his Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724) Daniel Defoe wrote of Greenwich:

Here several of the most active and useful Gentlemen of the late Armies … are retired … Several Generals, and several of the inferior Officers, I say, having thus chosen this calm Retreat … Other gentlemen still in service, as in the Navy Ordnance Docks, Yards &c. as well while in Business, as after laying down their Employment, have here planted themselves.[5]

The design for Hosier’s house has been attributed to the architect John James.[6] He was a clerk of works for the Royal Hospital for Seamen and had built a house for himself nearby.

Hosier, however, did not have much time to enjoy his new home. In 1727, together with about 4,000 other seamen, he died of yellow fever after being sent to Porto Bello in modern-day Panama to blockade Spanish treasure ships. The episode was commemorated in a popular ballad, Admiral Hosier’s Ghost.

Find out more about Admiral HosierChesterfield House

On Hosier’s death a drawn-out legal dispute ensued between his wife and his mother’s relations until, in 1740, the lease was sold to John Stanhope. In turn, on his death in 1748, this passed to his elder brother, the politician and diplomat Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield (1694–1773). Earlier that year Chesterfield had resigned as Secretary of State, marking his gradual withdrawal from politics and effectively ending his long public career.[7]

Lord Chesterfield was initially unenthused about his new home. No doubt he would have preferred somewhere upstream in fashionable Richmond or Twickenham, near his friend Henrietta Howard at Marble Hill.[8] None the less, he soon came to embrace life at Blackheath.

His home became a place to indulge his interests. As an avid collector of paintings, he invested in a new gallery to the south of the house, nearly doubling the building’s size and encroaching, illegally, through the park wall. He also remodelled the central dining room.[9]

Ranger’s House was also a retreat for Lord Chesterfield, even more so when from 1752 he began to lose his hearing. Here, in the summer months, he read, wrote and tended to his garden, of which he jokingly wrote in 1754, ’I converse with my equals, my vegetables, which I found in a flourishing condition’.[10]

It was also from Ranger’s that Chesterfield wrote many of the hundreds of letters for which he has since become well known.

Read more about Lord ChesterfieldFrom private to official residence

After Chesterfield’s death in 1773 the house passed to his godson and heir, Philip, 5th Earl of Chesterfield. In 1783 he sold it to Richard Hulse, an art collector, barrister and deputy governor of the Hudson Bay Company of Canada. Hulse built a new wing at the north end of the house, balancing Chesterfield’s gallery.

In 1807 Augusta, Dowager Duchess of Brunswick, sister of George III, took up residence at Ranger’s House, which was then known as Brunswick House. So began the long association of the property with the Crown. The duchess moved to Greenwich to be near her daughter, Caroline, Princess of Wales (later Queen Caroline), who, after separating from her husband, the future George IV, in 1796, lived at the property next door, the now-demolished Montagu House.

The adjoining gardens of the two houses were connected and 15 acres of the royal park enclosed, no doubt for greater privacy.

In 1806 Caroline had been appointed Ranger of Greenwich Park, an honorary position granted by the monarch. This came with a residence, nearby Queen’s House. Because that was in a poor state of repair Caroline remained at Montagu House which, after her departure, was intended as the next official residence of the Ranger of Greenwich Park.

At Montagu House, Caroline established a rival Regency ‘court’ where she frequently entertained the great and good of society.[11] These informal entertainments and Caroline’s reportedly reckless and spirited behaviour did not pass without comment from the royal family, or without repercussions. In 1806 a so-called ‘delicate investigation’ was established to explore rumours of Caroline’s infidelity and falsely reported pregnancy. Amid increasingly tense relations with the Crown, and given a financial incentive to leave by the government, Caroline left England in 1814.[12]

After she had left, the Crown surveyors found Montagu House to be poorly planned and constructed. On their recommendation, it was demolished, and Ranger’s House, as it became known, instead became the official ‘grace and favour’ residence for the Rangers of Greenwich Park.

Read more about Augusta and CarolinePrincess Sophia Matilda

The first Ranger to live at the present Ranger’s House was Princess Sophia Matilda, niece of George III. Before her arrival in 1815 extensive repairs were required. Woodwork was replaced or made good, stonework, glass and ironwork repaired, and the whole house repainted. As well as this, a covered walkway was added to the house entrance and new water closets were installed.[13]

Chesterfield’s wing was divided into three reception rooms and, like the rest of the house, richly decorated. The sales catalogue after Sophia Matilda’s death describes the rooms as having ‘fawn damask’ curtains, elegant furnishings, and an abundance of ornaments and ‘objects of taste’, from high quality china to intricately carved timepieces.[14]

Sophia Matilda lived in her newly refitted and refurnished home with her lady-in-waiting, Lady Alicia Gordon, and, as the 1841 census records, 17 servants.[15] She became the longest serving resident of Ranger’s House, living there until her death in November 1844.

Although we know little of her life at Ranger’s, she seems to have become immensely popular in the local community. The newspapers reported on the crowds of people who paid their respects as her body lay in state at Ranger’s House. Later, a ‘large concourse of people’ gathered at the start of her funeral procession ‘to witness the funeral obsequies of one so generally respected, and, locally so much endeared by acts of private beneficence’.[16]

A ‘grace and favour’ residence

The next Ranger was the antiquarian and politician George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen. He was Foreign Secretary when he was made Ranger in 1845 and became Prime Minister from 1852 until 1854. His son Lord Haddo and daughter-in-law Mary lived at Ranger’s with their young family until 1855, after which the house was left more or less unused until Aberdeen died in 1860. Lord Canning, another distinguished public servant, was then appointed Ranger, but his residence was short-lived. Both he and his wife died within seven months of being granted the house.

1862 saw the return of a royal to Ranger’s, with the arrival of 12-year-old Prince Arthur of Connaught, the third son of Queen Victoria. He was sent to Ranger’s with his tutor, Major Elphingstone, to study for a place at the Royal Military Academy. Once there he followed a strict regime. He was only allowed to play twice a week with playmates, taking part in military games with forts in the gardens, perhaps like those at Osborne House. Prince Arthur embarked on a successful military career, retaining Ranger’s House until he was 22.

Four years after her son’s departure, in 1877 Queen Victoria appointed the widowed Countess of Mayo as Ranger of Greenwich Park. Her husband had been assassinated in the Andaman Islands five years earlier, while he was Viceroy of India.

The Last Resident of Ranger’s House

The last Ranger to occupy Ranger’s House was Field-Marshal Lord Wolseley, who lived there after retiring from active service with his wife, Louisa, and daughter. Their tenure was short. In 1890 Wolseley was made Commander-in-Chief in Ireland and moved to Dublin. Louisa and their daughter joined him the following year.

Despite their short stay at Ranger’s, Lady Wolseley, a collector of 18th-century furniture and applied art, redecorated the house. Correspondence suggests that the Gothic Revival architect GF Bodley advised her in this.[17] Among the interior alterations was the fitting of new bookcases, which evidently housed Wolseley's large book collection. Objects in the Hall referenced Wolseley’s career and interests through the display of a ‘large collection of military and sporting trophies’.[18]

Changing Fortunes

Queen Victoria transferred Ranger’s House to the Commissioners of Woods and Forests in 1897 in exchange for the restoration of Kensington Palace. The following year the grounds at the back of the house were reabsorbed into Greenwich Park.

After lobbying by the local community, in 1902 the London County Council bought Ranger’s. It was used as changing rooms and a tea room, and the grounds were converted into a bowling green and tennis courts.

During both world wars the house was put to use. In the First World War, together with McCartney House next door, Ranger’s became the headquarters for the No. 2 Reserve Horse Transport Depot, which was formed on Blackheath in 1915. It was requisitioned in the Second World War, during which the stable block was damaged by bombing, and later demolished.[19]

Collections at Ranger’s

Ranger’s House was restored in 1959–60 and again in 1973–4. During this period it was put to varied uses. Initially the gallery was used for events and local history exhibitions, the dining room as a restaurant and the upper floors as offices. The rose garden at Ranger’s today was laid out around 1960. In 1986 the house passed from the Greater London Council into the care of English Heritage.

With changes of ownership over time, Ranger’s House has no collection of its own. However, it has housed a number of collections over the years. It was home from 1974 to the Suffolk Collection (now at Kenwood) and from 1985 to the Dolmetsch collection of musical instruments.

Ranger’s now houses the world-class collection of fine and decorative art amassed by Julius Wernher. A German-born businessman, Wernher made a fortune from dealing in South African gold and diamonds at the turn of the 20th century. This enabled him to buy many outstanding artworks to fill the rooms of his London home, Bath House, and country estate, Luton Hoo, in Bedfordshire. Today over 700 objects from his collection, ranging from ancient Greece to the 19th century, are on display at Ranger’s House.

Find out more

-

Visit Ranger’s House – The Wernher Collection

Discover a diamond magnate’s fabulous jewels in an elegant Georgian villa, now best known as the exterior of the Bridgerton home in the Netflix series.

-

Ranger’s House and Admiral Hosier’s Ghost

Find out why the death of Admiral Francis Hosier, the first resident of Ranger’s House, and the devastation of his fleet, became the subject of a scathing musical attack on the government of the day.

-

Lord Chesterfield at Ranger’s House

Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, politician and famed letter-writer, was the most celebrated owner of Ranger’s House. Find out more about him and his life there.

-

The Real Bridgerton: A Royal Duchess at Ranger’s House

Ranger’s House plays a starring role in Netflix’s Bridgerton series. But the house has its own dramatic story to tell of royals, scandal and entertainments during the era in which Bridgerton is set.

-

About the Wernher Collection

Find out more about the Wernher Collection, the man behind it, and how it came to be displayed at Ranger’s House.

-

Highlights of the Wernher Collection

Explore a selection of works from the Wernher Collection and discover what they reveal about how the material culture of Europe was changed and shaped over hundreds of years.

-

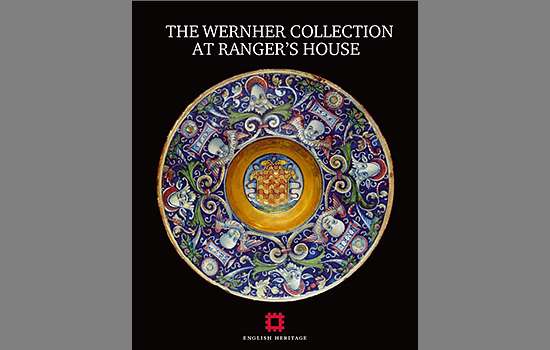

Buy the guidebook

This fully illustrated guidebook includes a tour and full history of the house and the Wernher Collection, and gives many fascinating glimpses into life at Ranger’s.