UNLIMITED ACCESS TO OVER 400 HISTORIC PLACES

Live and breathe the story of England at royal castles, historic gardens, forts & defences, world-famous prehistoric sites and many others.

Read about the man at the centre of the most turbulent period of England’s history, and learn about the statue dedicated to him in Trafalgar Square, London.

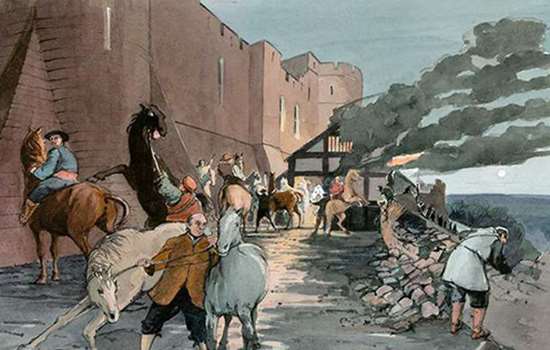

Find out how the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces after the Battle of Worcester in 1651, hiding at Boscobel House in Shropshire.

Read about how Lady Blanche Arundell heroically led a small band of men and women in defence of her home, Old Wardour Castle, when it came under siege during the English Civil War.

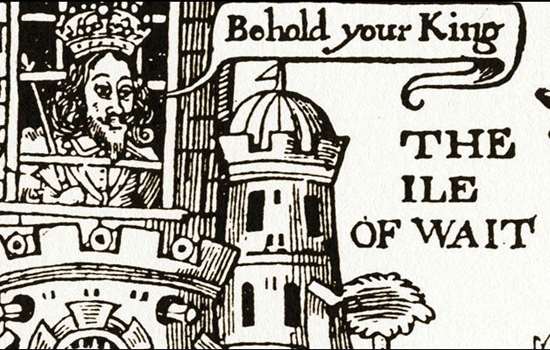

Jane Whorwood was one of the agents behind attempts to free Charles I from captivity on the Isle of Wight, notably from Carisbrooke Castle, in 1648.

The heroic actions of James Chappell after an explosion on Guernsey in 1672 were enshrined in legend.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was one of the most prolific female authors and philosophers of the 17th century, writing at a time of immense political upheaval.

Read about Lady Anne Clifford, a staunch Royalist who left London to reclaim and restore her family estates in northern England that had been damaged in the Civil Wars.

George Villiers became a favourite of King James I after their first meeting at Apethorpe in 1614. Read about James and George and the surviving love letters between them.

Find out more about Elizabeth, Countess of Kent, and her connection to the first cookbook in England to trade on a celebrity name.

Read about poet John Dryden, his shifting loyalties after the Civil Wars and where to find his London blue plaque.

Read about diarist Samuel Pepys, a once Republican sympathiser who swiftly adopted Royalist loyalties once Charles II was restored to the throne.

Read about Sir Christopher Wren, Britain’s most famous architect. Following the Great Fire of London in 1666 he built dozens of new churches, including St Paul’s Cathedral.

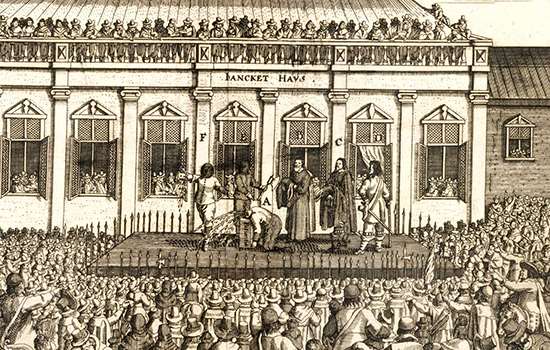

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

In June and July 1646, Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the Civil War.

Discover how Donnington Castle in Berkshire held out for Charles I during a 20-month siege in 1644–6, and played a key role in the Second Battle of Newbury.

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner of Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

How a major sea battle between the Dutch and the Spanish on the Kent coast revealed as much about the English navy as it did about its participants.

Discover how the reorganisation of the Parliamentarian army during the Civil Wars marked the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

How a fort, built for troops manning the frontier of Roman Britain, became a locus of crime and unrest in Stuart England.

Listen to these podcast episodes to learn more about some of our Stuart sites and the collections and people associated with them.

These are some of our sites which either have buildings dating from the Stuart era or where significant events took place during that time.

From the grand country houses of the early Stuart period to Christopher Wren's new churches that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

The economy of much of Stuart England was largely based on traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade.

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period.

How an extravagant but unfinished castle tells a story of family rivalry and competitive housebuilding in 17th-century England.