‘A captive girl’

In July 1850 Frederick Forbes, a well-respected British naval captain in the West Africa Squadron (WAS), visited King Gezo (or Ghezo) of Dahomey (present-day Benin) on a diplomatic mission. For many years Britain had played a central role in the transatlantic slave trade, but in 1833 abolished slavery throughout its empire. The WAS’s mission was to undermine the trade, both by intercepting French and Spanish slave ships and by using diplomacy to dissuade local leaders from taking part in the trade. King Gezo was the dominant figure in West Africa in the supply of enslaved people, as it was his main source of revenue.

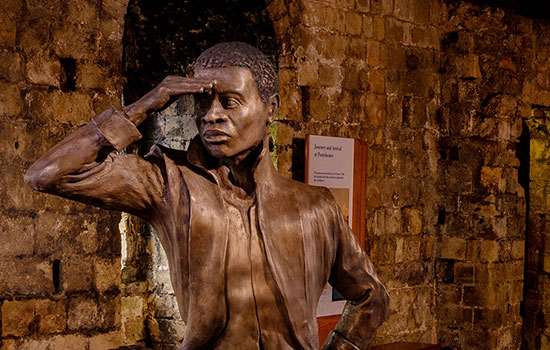

At such encounters it was standard practice to exchange gifts. But among the gifts Gezo offered to Forbes – including a keg of rum, ten heads of cowries, and a ‘rich country cloth’ – was an unexpected one: a ‘captive girl’. The child, whose name was Omoba Aina, was from the Egbado (known today as Yewa) clan of the Yoruba people. She had been captured two years earlier when Gezo’s army attacked her village, Oke-Odan. Her parents were killed during the raid.

It is not clear whether Gezo offered the child freely or whether Forbes bargained for her, but she clearly impressed him. Forbes believed that the fact that Gezo had held her for two years and not sold her to slave traders meant she was likely to be of high status. He also feared (with reason, as Gezo was known to sacrifice high-status captives) that she was destined to be offered as a human sacrifice.

So Forbes accepted Aina as a gift on behalf of Queen Victoria. Before returning to England he took her to the Church Missionary Society in Badagry, a former slave-trading port, where she was baptised Sarah Forbes Bonetta, after his own name and that of his ship. The change of name signalled her separation from her African roots.

In his journal Forbes noted that on the long voyage back to England in HMS Bonetta she became ‘a general favourite’ with the crew, who called her Sally.

Royal protégée

Some months after their arrival in England, Forbes presented Sarah to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. The queen described Sarah in her journal entry for 9 November 1850, the date of their first meeting:

Capt: Forbes saved her life, by asking for her as a present. … She is 7 years old, sharp & intelligent, & speaks English. She was dressed as any other girl. When her bonnet was taken off, her little black woolly head & big earrings gave her the true negro type.

Victoria seems to have decided at this point that she should be responsible for Sarah’s education and welfare, as Forbes had no doubt hoped.

So the extraordinary transformation of Sarah’s life began. She initially stayed with the Forbes family, and visited the queen regularly. Forbes was delighted with her progress:

She is a perfect genius; she now speaks English well, and has a great talent for music. … She is far in advance of any white child of her age, in aptness of learning, and strength of mind and affection.

In 1851, though, Sarah was sent to the Church Missionary Society school in Freetown, Sierra Leone, with the intention that she should become a missionary herself. (She had begun to suffer from coughs, and there was a widespread belief at the time that the English climate was harmful to Africans’ health.)

While Sarah was in Freetown the queen continued to send her presents and books. Apparently unhappy there, Sarah returned to England after four years. Victoria then placed her with the Schoen family, former missionaries in Africa, who lived in Gillingham, Kent. Sarah lived with them for six years before moving to Brighton, much against her wishes, where Victoria had arranged for a Miss Welsh to oversee her introduction into British society.

The Schoens’ daughter Annie, who taught her French and English, later recalled that Sarah ‘was very bright and clever, fond of study, and had a great talent for music’. According to Annie:

[Queen Victoria] gave constant proofs of her kindly interest in her. At the Midsummer and Christmas seasons she often went either to Windsor or Osborne to stay in the family of one of the officers of Her Majesty’s Household, and was frequently sent for by the Queen to see her privately.

Sarah’s accomplishments were keenly scrutinised, particularly in the press, by those keen to discover what light her achievements would shed on racist beliefs, then widely held, about the intellectual inferiority of African people.

Marriage

When Sarah was 19 a Sierra Leone-born merchant, James Davies – whose own parents were Yoruba Africans who had been freed from slavery – declared his interest in marrying her. Sarah and James were first introduced when Sarah was at the mission school in Sierra Leone, but barely knew each other. Sarah described her feelings in a letter to Mrs Schoen:

Others would say ‘He is a good man & though you don’t care about him now, will soon learn to love him.’ That, I believe, I never could do. I know that the generality of people would say he is rich & your marrying him would at once make you independent, and I say ‘Am I to barter my peace of mind for money?’ No – never!

But the queen approved of the match, and whatever Sarah’s misgivings may have been, the couple married on 14 August 1862. On her marriage certificate, Sarah gave her first name as Ina – perhaps a variant of her African name.

Sarah’s status as a protégée of the queen ensured that the wedding was a lavish affair. There was also widespread curiosity about her as a supposed ‘African princess’. The Bishop of Sierra Leone officiated at the ceremony, and large crowds gathered to witness the spectacle. Newspapers reported that there were 10 horse-drawn carriages and 16 bridesmaids, and that the wedding party was made up of ‘white ladies with African gentlemen, and African ladies with white gentlemen’.

Shortly afterwards Sarah and James had a series of photographs taken by Camille Silvy, the celebrity photographer of the day, underlining their status in society. The queen herself may have commissioned them.

Return to Africa

As Davies’s business was in Africa, not long after the wedding the couple moved to Sierra Leone, and later to Lagos. They named their first daughter Victoria (born in 1863) after the queen, who became her godmother. In December 1867 Sarah presented the child to her royal namesake, and when Victoria was christened the queen sent her a gold cup, salver, knife, fork and spoon.

Sarah and James had two more children, but by the late 1860s Sarah was suffering from tuberculosis, for which there was no cure. She eventually travelled to Madeira, hoping that its temperate climate would help with her condition. But she died there on 15 August 1880, at the age of 37.

Sarah’s daughter Victoria, then 17, heard the news of her mother’s death just as she was travelling to Osborne to visit the queen, who reported that ‘my black godchild … was dreadfully upset & distressed. … Her father has failed in business, which aggravated her poor mother’s illness. … I shall give her an annuity.’ The queen then paid for Victoria to be educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, and stayed in touch throughout her life.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta’s life followed a remarkable path. Her story is not typical of black women living in Victorian Britain. But it is interesting for what it reveals of Victorian attitudes to race – not just of Queen Victoria, but of those who viewed her life as a social experiment. Her accomplishments were keenly observed by those on opposing sides of the debate about whether Africans could be ‘civilised’ under British guidance.

As for Sarah herself, we can only wonder what she made of her journey from traumatic childhood to ‘privileged’ upbringing, controlled and shaped by the most powerful ruler in the world, far from the place and culture of her birth.

Further reading

Joan Anim-Addo, ‘Queen Victoria’s black “daughter”’, in Black Victorians/Black Victoriana, ed Gretchen Gerzina (New Brunswick, NJ, 2003), 11–19

Joan Anim-Addo, ‘Bonetta [married name Davies], (Ina) Sarah Forbes [Sally]’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2015) (subscription required; accessed 21 Sept 2020)

Caroline Bressey, ‘Of Africa’s brightest ornaments: a short biography of Sarah Forbes Bonetta’, Social & Cultural Geography, 6:2 (2005), 253–66 (subscription required; accessed 21 Sept 2020)

A Elebute, The Life of James Pinson Labulo Davies: A Colossus of Victorian Lagos (Lagos, 2013)

FF Forbes, Dahomey and the Dahomans: being the journals of two missions to the king of Dahomey and residence at his capital in the years 1849 and 1850 (1851) (accessed 1 Oct 2020)

A Higgens, ‘Queen Victoria’s African protégée’, The Church Missionary Gleaner, 8 (1881), 22 (accessed 1 Oct 2020)

D Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (London, 2016)

Find out more

-

Introduction to Victorian England

During Queen Victoria’s long reign, Britain acquired unprecedented power and wealth, and its reach extended across the globe.

-

Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria was crowned when she was just 18, and her reign lasted 63 years. Find out more about her life and reign.

-

Black history

Black history is a key part of England’s story, and helps us to reflect on the connections between the past and present.

-

WOMEN IN HISTORY

Read about the remarkable lives of some of the women who have left their mark on society and shaped our way of life – from Anglo-Saxon times to the 20th century.