The Wall and its forts

Hadrian’s Wall, built in about six years from AD 122, crossed the country from sea to sea, between Wallsend in the east and Bowness-on-Solway in the west, a distance of 73 miles. It defined the north-western frontier of the Roman empire.

In their original design, Roman planners envisaged a stone or turf wall, with a deep V-shaped ditch forming an additional obstacle on its north side. A guard force was housed in fortlets (milecastles) spaced about 0.9 miles apart, and in pairs of watch towers (turrets) between them. A larger force occupied a network of forts a few miles south of the Wall, with a few to the north.

During construction, the planners changed their minds and built large forts at strategic locations astride the Wall, to place a substantial fighting force right on the frontier. They also built the Vallum, a broad ditch with a mound on each side, running along the Wall to the south, thereby creating a broader military zone.

Slightly later still, the army built two more large forts. One of these was at Carrawburgh, to make safe a long gap between forts at Housesteads and Chesters. We know from excavations that at Carrawburgh the builders levelled part of the Vallum before building the fort, revealing that it was an afterthought, which required work already completed to be removed. It is not certain when this occurred, but a date of about AD 130 – some eight years after work on Hadrian’s Wall began – has been suggested.

The people of Brocolitia

We know something of the people who lived at Brocolitia thanks to the many Roman inscriptions found there, on altars, building dedication stones and tombstones. They record both military units and individuals. Some units were stationed in the fort or erected buildings there, while individual soldiers may have been part of the garrison, or visiting to make an offering at a favourite shrine in the civilian settlement.

The military units stationed at Brocolitia were auxiliaries – troops originally recruited from conquered people in other Roman provinces or from beyond the empire, rather than citizens of Rome. They were mostly infantry, although one unit – the Batavians – probably included some cavalry.

Several commanding officers of the Batavians, all career officers posted to Brocolitia for a few years, dedicated altars to Mithras and Coventina. One of them, Aulus Cluentius Habitus, was from Larinum, now Larino, in east central Italy. Other soldiers included Longinus, a trumpeter, another who was a standard bearer, and Quintus, an engineer.

Others present at Brocolitia included a junior officer (optio), two cavalry officers (decuriones) and Tranquila Severa and her family, who dedicated an altar to the Mother of the Gods. A few individuals either had Germanic names or described themselves as German, including Vinomathus, Maduhus, and Aurelius Crotus.

Most touching of all, perhaps, is a tombstone which records the deaths of Regulus, aged 34, his wife at the age of 30, their very young son, and a daughter who lived only a few days.

The garrison

The military units recorded on Roman inscriptions from Brocolitia are:

- the first cohort (or regiment) of Aquitanians, originating in west and south-west France

- the first cohort of Tungrians, originally raised in eastern Belgium/south-east Netherlands

- a detachment from the second cohort of Nervians, raised in central Belgium

- the first cohort of Batavians, originating in the Netherlands. Stationed at Brocolitia from about AD 237 or possibly earlier, they were still recorded as the garrison in the Notitia Dignitatum, a list of civil and military posts probably compiled in the late 4th or early 5th century AD

- the first cohort of Frisiavones, from the southern Netherlands

- the first cohort of Cubernians, from eastern Germany

- a detachment of the Sixth Legion (heavily armoured infantry, originally composed of Roman citizens).

Not all of these were in garrison – some inscriptions may have been made by units carrying out building work, or by soldiers visiting to make a religious dedication.

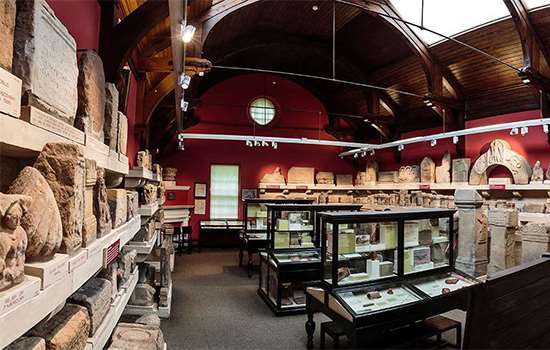

Image: Altar found at Carrawburgh dedicated to Mithras by Marcus Simplicius Simplex, prefect, a commander of a military unit (probably the first Batavians). The altar is now in the Great North Museum: Hancock (there is a replica at Carrawburgh)

© Carole Raddato (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The site of Brocolitia

The fort sits on the edge of moorland, on a watershed overlooking the valley of Meggie’s Dene Burn, a tiny stream that drains southwards into the river South Tyne.

It has the playing-card shape typical of Roman forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries. Today this is visible as an earthwork platform whose edges cover the remains of the fort’s enclosing stone wall, which is known to survive up to 1.5 metres high below the turf. The fort’s north wall was formed by Hadrian’s Wall itself, which was reduced here in about 1752 during the construction of a military road (now the B6318), built to link the Georgian garrisons at Newcastle and Carlisle. Any remains now lie beneath this road.

Earthwork remains of the civilian settlement or vicus are visible west and south-west of the fort, on a series of artificial terraces on the slope down to Meggie’s Dene Burn, with the stone-built temple of Mithras lying in the valley bottom. Sub-surface surveys have shown that the remains of streets and buildings of the vicus also survive around the south and east sides of the fort.

The Anatomy of the Fort

A LiDAR (light detection and ranging) scan of Carrawburgh. The fort is clearly visible, along with earthworks of the vicus to the west (left). South and east of the fort any remains of the vicus are obscured by the parallel lines made by later ploughing

© Environment Agency. All rights reserved

The fort has many typical features. A high stone wall, 1.7 metres thick, supported on the inside by an earth rampart and incorporating gates and towers, enclosed an area of about 1.4 hectares, enough space for a unit of 500 soldiers. Outside the west wall are earthwork traces of two closely spaced, parallel defensive ditches that may originally have extended around the south and east sides to form a continuous obstacle.

The wall had four gateways, each of which probably had two passageways between twin towers. The positions of the southern, eastern and western gates are known. Two interval towers spaced along the fort wall – one in the north-west corner and another midway between the west gate and the south-west corner – have also been located. There would have been six or more originally.

We know little of the buildings inside the fort. Limited explorations by archaeologists have revealed that the headquarters building (principia), at the centre of the fort, had a rectangular plan arranged around an open courtyard. A cross-hall (basilica) and offices formed the south range, while covered porticoes framed the other sides – though the western portico was converted into rooms in the late 2nd century. A strong room, where pay and important documents were kept, has been excavated under the central room of the south range (the shrine of the standards or aedes) and a well was found in the courtyard.

Parts of other buildings have been revealed in small excavations – two barracks and a third building in the north-west part of the fort, and two granaries west of the principia.

The vicus

A recent survey has revealed something of the buried remains of the vicus. It probably included several streets, plot boundaries and buildings – houses, shops, workshops, inns and temples – covering an area of about 4 hectares, like a small village. Most of it remains unexcavated.

But much is known about the valley of Meggie’s Dene Burn, where three shrines and a bath-house have been excavated. It is likely that the valley held even more shrines to deities associated with life-giving water, perhaps visited by people from other communities in the region as well as those of Brocolitia.

Coventina’s well

Now known as Coventina’s well, a shrine to Coventina – a local water goddess – stood close to the head of the valley. It had a stone wall enclosing a space approximately 12 metres square, possibly open to the air. This contained a central rectangular basin or well, 2.6 by 2.4 metres, formed around a spring.

Excavations in 1876 uncovered offerings that included around 16,000 coins, two dedication slabs to Coventina, ten altars to her and the goddess Minerva, a sculpture of three water nymphs, the head of a male statue, two clay incense burners, and other votive objects.

The temple of Mithras

A little further downstream are the remains of a small mithraeum, a temple built around AD 200. It was dedicated to Mithras, the god of a Roman religious cult that emerged in the 1st century AD and spread across the provinces. Its inspiration may have come from the Zoroastrian deity Mithra, whose worship the Romans encountered on their eastern borders.

The rectangular stone temple is small and secluded, with one entrance, and probably no windows. This would have created the dark atmosphere resembling the cave in which, according to legend, Mithras killed a sacred bull and feasted with the sun god, Sol. The mithraeum may have symbolised the cosmos, with worshippers undergoing a spiritual journey from life to afterlife and back, and then feasting in celebration of Mithras.

The Mithraic cult had a seven-grade hierarchy, with passage from one to the next requiring an ordeal of mental or physical strength, in the face of a real or threatened peril. Membership was popular among soldiers. At Brocolitia three commanding officers of the fort dedicated the altars whose replicas you can see in the temple today.

The temple was rebuilt or refurbished four times. It had fallen out of use by about AD 350, by which time it had suffered some deliberate desecration, robbing for building materials and waterlogging from the adjacent burn. Afterwards the site was incorporated into a Roman rubbish tip.

A cutaway reconstruction drawing of the temple of Mithras at Carrawburgh, imagining its appearance during a ceremony in the 3rd century AD. A novice has undergone an ordeal in the outer room (left) and is about to be revealed to the worshippers in the main area

© English Heritage Trust (illustration by Peter Urmston)

Shrine of the Water Nymphs and the Genius Loci

Immediately beside the mithraeum stood a small open-air shrine, dedicated to water nymphs (nature goddesses) and the genius loci, the protective spirit of the locality. Also based around water, it comprised a single altar, a well and an apsidal wall containing a seat.

Bath-house

The bath-house was excavated in 1873 but is no longer visible. It stood a little further downstream of the mithraeum, towards the southern edge of the vicus. Water would have been channelled to it from the burn. It contained a typical sequence of rooms including a changing room, cold, warm and hot rooms, and cold and hot plunge baths.

Brocolitia today

Although the temple of Mithras has been in the care of the state for many years, until recently the fort was in private hands. However, in early 2020 the owner donated the site to the nation. Legal ownership of Carrawburgh transferred to Historic England, and English Heritage now cares for it as part of the National Heritage Collection.

Many of Brocolitia’s stories remain to be discovered because it has not been extensively explored by archaeologists. Although it has suffered from gradual decay of its buildings, and the taking of stone for the military road and for local farmsteads and walls, it has not been damaged by building, being largely in agricultural use since Roman times. This means it holds great potential – a precious resource for future research to enhance our understanding of Hadrian’s Wall.

By Paul Pattison

Related content

-

Carrawburgh Roman Fort Collection Highlights

Highlights include objects discovered at the shrine to the goddess Coventina, comprising more than 20 altars, about 16,000 coins and many other offerings.

-

History of Hadrian’s Wall

Read more about the history of Hadrian’s Wall, the north-west frontier of the Roman empire for nearly 300 years.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman empire.

-

History of Housesteads Roman Fort

Lying midway along Hadrian’s Wall, Housesteads is the most complete surviving Roman fort in Britain and one of the best-known from the whole Roman empire.

-

History of Chesters Roman Fort

The cavalry fort, known to the Romans as Cilurnum, housed some 500 cavalrymen and was occupied until the Romans left Britain in the 5th century.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.